But is it Chocolate? Really?

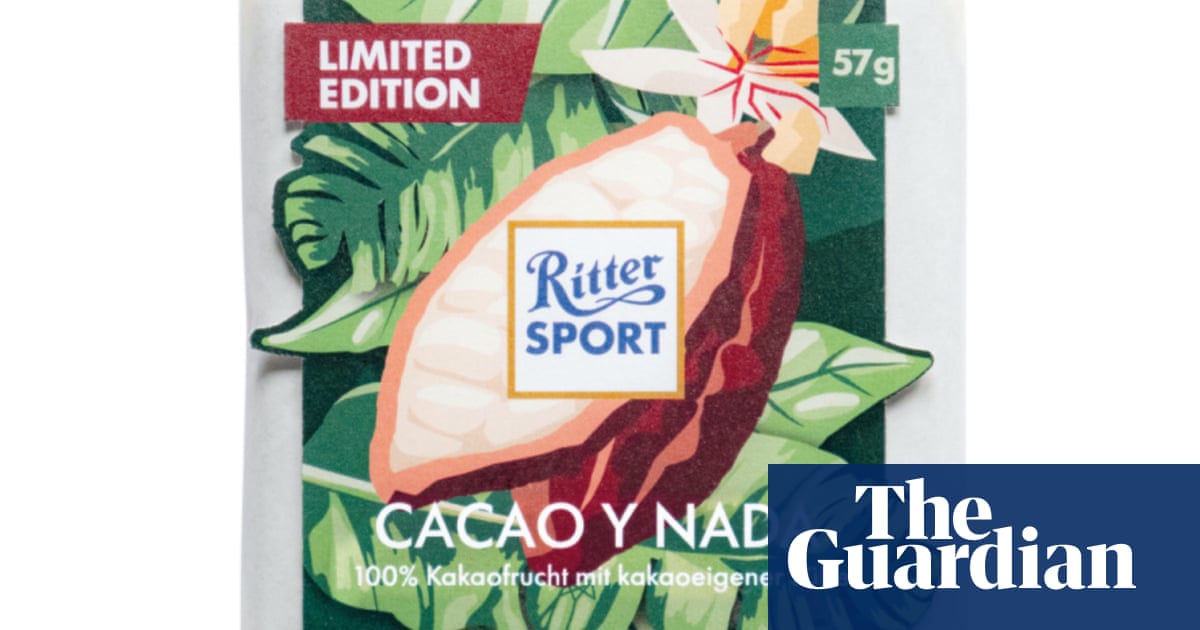

Ritter joins the field of companies making chocolate sweetened with cacao sugar.

TL;DR

Why yes, yes it is. Of course it is.

Some Background

For the long history of processing cacao, very little was done, commercially, with the pulp and juice. This is despite the fact that, historically, it is likely that collecting cacao juice and allowing it to spontaneously ferment into a low-alcohol beverage was widely practiced before anyone figured what to do with the seeds.

There are many reasons for this, and it was the introduction of a commercially-viable refrigeration system – another key invention alongside the cocoa butter press, alkalization, and the conche – that made the chocolate industry as we know it today possible.

For centuries, the key derivative products of cocoa – the ones that were exploited widely – were (and are) beans, nibs, liquor, butter, powder, and chocolate. While uses for discarded pods (fertilizer, charcoal), pulp (frozen), and juice (beverages of many kinds) have been made in many parts of the world, developing commercial uses cases outside of the country of origin has been difficult until recently.

Allow Me to Digress ...

When you think about it (as I have), the global laser focus on the beans (and shades of brown, until recently) is a mystery.

If just 100 liters of juice is produced from a metric tonne of wet cocoa, the total amount of cocoa juice that was just allowed to drain away in 2020 was, conservatively, more than four hundred million liters. This juice is highly acidic (ph between 3 and 4) which means it can be considered (and is in some producing countries and contexts) to be toxic waste.

Fresh cocoa juice can also contain a lot of sugar and pectin which can also be upcycled into commercial products.

From my own experience helping to developing the supply chain for Solbeso (an 80 proof spirit distilled from fresh cacao juice), I can tell you that developing a reliable supply chain infrastructure capable of handling a highly perishable product in remote, hot, humid, locations where transportation is unreliable is very expensive; doubly so when air conditioning and refrigeration, both of which are dependent on reliable sources of electricity, are required.

... and Back

It actually makes economic sense to develop the infrastructure for upcycling, and, in my opinion, when considered more broadly, expanding cacao processing to create more different kinds of derivative products can be the means by which much of the systemic inequity in the cocoa > chocolate supply chain can be addressed in socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable ways.

The Gordian knot that needs to be slashed is the idea that the entire edifice of chocolate depends on farming jobs. In discussions with senior members of the sustainability and R&D teams at Barry Callebaut during the global Wholefruit launch in September 2019 (see More Reading, below), it became clear to BC that investment in this infrastructure could change the entire labor ecosystem in-country. The children of cocoa farmers could aspire to jobs managing production lines or logistics or many other tasks, many requiring advanced education and training, rather than seeing a future as a smallholder farmer.

Cacao Sugar to the Rescue?

Global giants and raw startups in the food industry have spent millions of dollars in research into upcycling and perhaps the most visible two are a) fresh juice, and b) sugar.

Nestlé was the first to come to market with a “100% cocoa” content chocolate sweetened with cacao sugar. This marketing plays fast and loose with the current definition of what “cocoa content” measures – the non-fat solids and fat derived from beans. While cacao sugar is derived from cacao, it is either a by-product of the pulp surrounding the seeds deliquescing during fermentation, or from the mechanical extraction of a portion of the pulp from the seeds before fermentation.

Nestlé released its cacao sugar-sweetened chocolate originally just surrounding aa KitKat and just in Japan. Within a year, Barry Callebaut announced its Wholefruit program which included not only couverture chocolates sweetened with cacao sugar, but examples of R&D in other areas, including juice concentrates and flours made from the pod.

In 2020 Felchlin announced that it was manufacturing a chocolate made from cacao sugar in collaboration with a startup in Ghana that was building infrastructure to pay farmers to capture fresh juice, then pasteurize and package it for export. Felchlin worked to convert the juice to a form that could be used in chocolate and ... made a chocolate that I found basically inedible on its own. The chocolate retains a lot of the acidic aroma and flavor of fermenting cocoa. While it might be interesting as an element in some dessert or confection, on its own I found it to be the first truly disappointing chocolate from them I have ever tasted. And I know the flavor profile was a deliberate choice based on correspondence with people involved in its development.

Which leads us to Ritter’s recent announcement of a chocolate sweetened with cacao sugar and the German government’s reaction that it’s not chocolate. Following is some press:

The German regulatory authorities’ reasoning is basically (according to the articles) that the bar is sweetened with cacao juice, which is technically not “sugar,” and the governing German food purity law (the chocolate equivalent of the Reinheitsgebot) says that in order for something to be legally labeled as chocolate, it must be made with a recognized sugar.

Therefore, Cacao y Nada cannot legally be called chocolate.

Key Takeaway ::

IMO, the German government’s view is shortsighted and regressive.

Your take? Let us know in the comments.

Listing image credit: Original by Daniele Levis Pelusi on Unsplash

More Reading