Chocolate Unboxed: To'ak El Niño Harvest 2016

At €30+ for a 50gr bar – and up to over €400 for some barrel-aged varieties in much more extravagant packaging – you would expect the unboxing experience to be pretty astonishing. And in this respect To’ak does not disappoint. But …

… as the photos will demonstrate, while the packaging is extravagant and up to the standards of a luxury brand (not just a luxury chocolate brand), it is at odds with important aspects of To’ak’s brand identity – particularly notions of sustainability. The reboxing experience also needs more thought.

Communicating About the To’ak Brand

To’ak has made a name for itself (literally) as the re-discoverer and conservator of ancient Peruvian Nacional cacao, and transforming those beans into the most expensive bars of chocolate currently on the market.

While there is a lot of marketing focus on the genetics, scarcity, quality, and work to preserve the beans themselves (and more recently in the exclusive nature of spirits used for cask aging), it cannot entirely escape notice that a whole lot of the retail price of the final product is wrapped up [pun intended] in the packaging.

Back in February (2020), I privately called the company out on some disingenuous marketing language in one of their email newsletters – they claimed they were paying 8x market price for their beans.

Taken literally – and this is the interpretation I believe most people would form – and the impression I formed from this claim – was they were paying 8x the ICCO daily price, then about US$2500/MT. This would mean they were paying over US$20,000 per tonne (metric ton, or MT) at the farm gate for their beans, an amount I found very hard to believe.

When asked for details on this claim, I was told they were actually paying 8x the local market price for wet mass (cacao en baba, or beans in fresh pulp) and they were doing the post-harvest processing on those beans themselves.

While 8x the local market price for beans in baba is a lot, especially when you consider To’ak is taking on all upstream market risk (just as Ingemann does in Nicaragua, and others do), it’s a far cry from paying over $20,000/MT to their farmers for their beans.

My hope is that they will work diligently to correct this impression and communicate what they are actually paying and actually doing clearly and precisely in ways that do not lead to confusion.

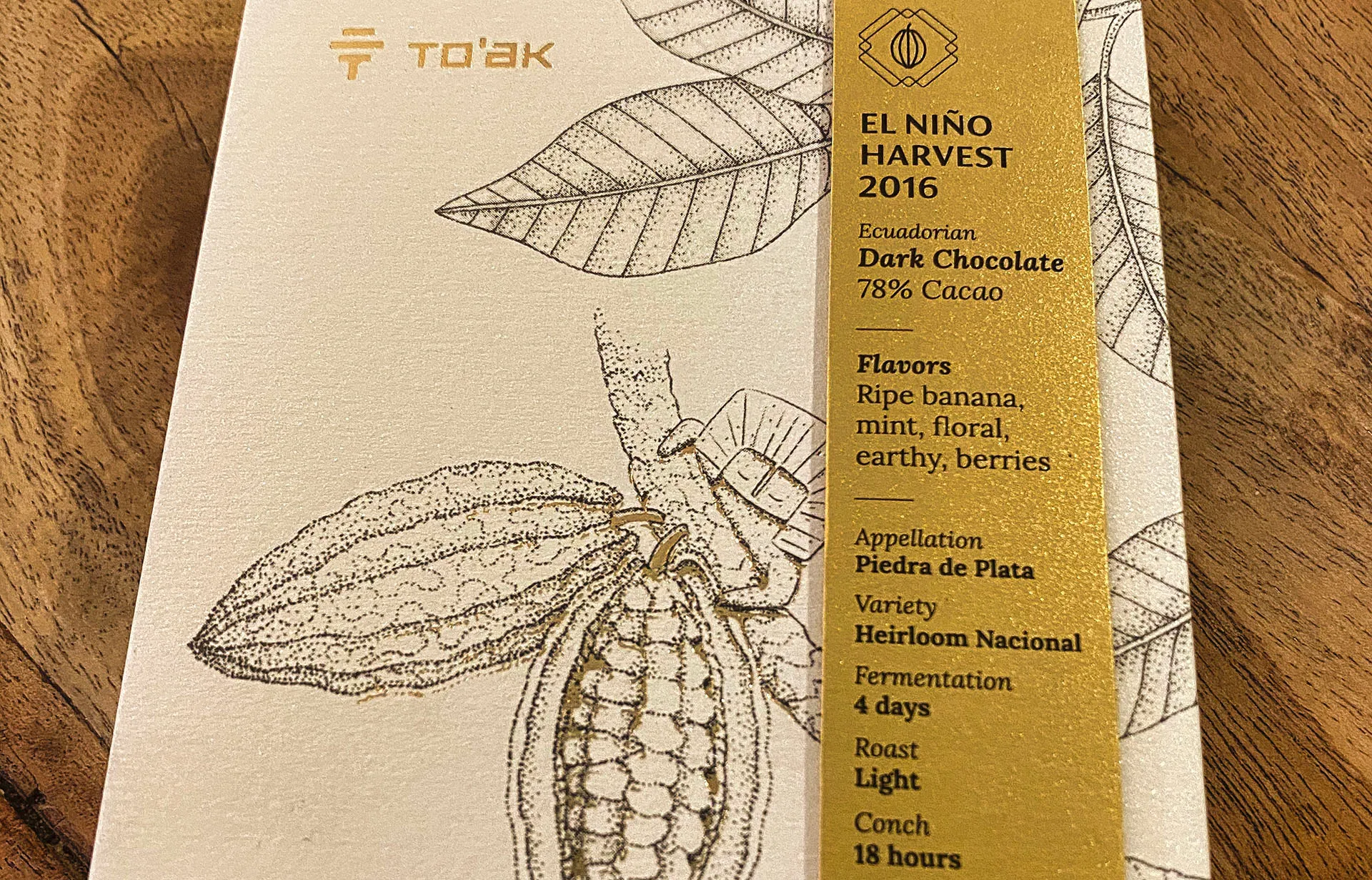

Reading (Some of) the Labels

Lid

The label on the outside front of the box provides a potential buyer with a lot of information about the provenance of the cocoa. This information signals that this is a specialty/craft product as it’s extremely difficult for industrial chocolate makers to provide this level of specificity about the beans they are using. This is a good thing.

What I find fault with is the use of the word “Appelation.” There are two active denominations of origin (DO) in Ecuador. The first is for Cacao Arriba and the other is for Sombrero de Montecristi – better known as Panama hats even though they were originally from Ecuador).

Within the Cacao Arriba DO there is no mention of Piedra Plata as a recognized geographic indicator that I can find. So claiming a formal appellation for Piedra Plata (silver stone) is a hyperbolic stretch.

Furthermore, claiming the variety as Heirloom Nacional is also a bit of hyperbole. The variety is a Nacional and this particular variety of Nacional has been awarded heirloom status by the FCIA’s Heirloom Cacao Preservation program, there is no actual variety called Heirloom Nacional.

Inner Lid

The label on the inner top lid makes claims that can also be seen as hyperbolic marketing-speak rather than being strictly true

- I think both Chuao (Venezuela) and Marañon (Peru) also lay claim to being the rarest and most highly-prized cacao in the world.

- I think it’s still an open question about the precise origin of cacao. While current thinking places it in the Upper Amazon River basin on the eastern slopes of the Andes there is, to my best understanding, some question about whether the origin is located in what is modern-day Ecuador or modern-day Perú.

One of the things I have learned over the course of my two=plus decades working in cocoa and chocolate is that no one boasts about using the second-best anything – everyone always uses the best, finest, rarest, or freshest ingredients. So when I see claims like these I personally tend to question them and not take them at face value.

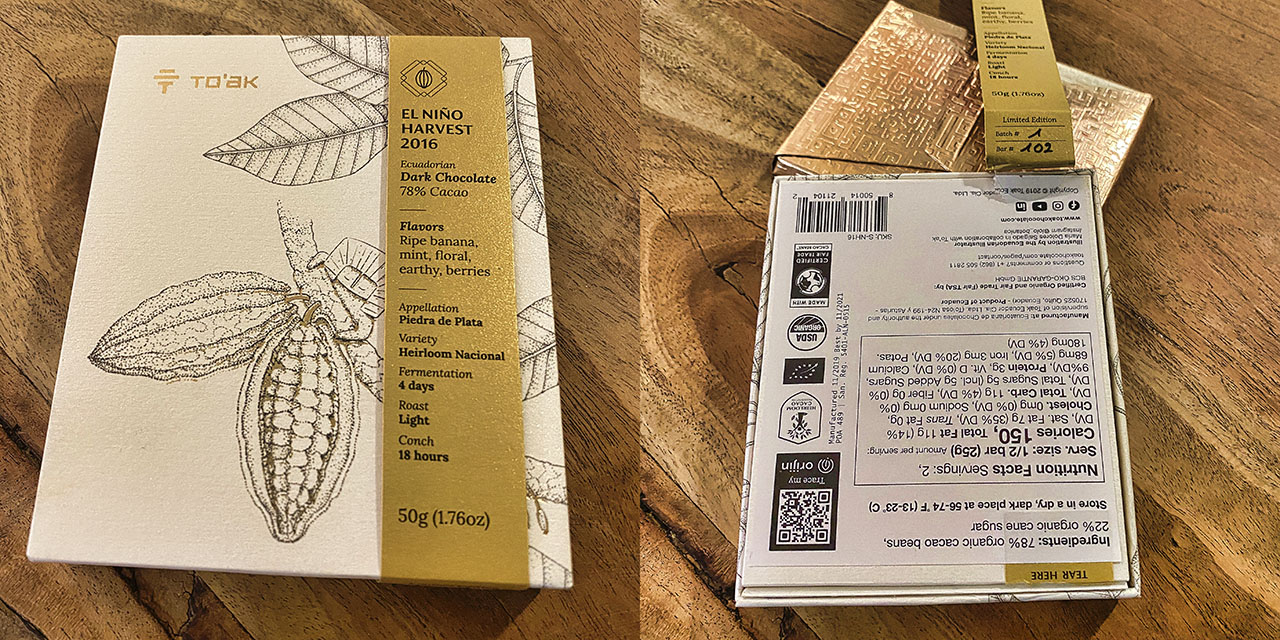

Base

To’ak are not themselves chocolate makers, though to be fair they do not communicate this impression on their packaging.

Their chocolates are made for them by Ecuatoriana, one of the largest industrial and private-label chocolate manufacturers in Ecuador, and this relationship is very clearly spelled out on the back of the box. To’ak’s having someone make their chocolates for them is not a bad thing – it is almost certainly much better chocolate because of this relationship; Ecuatoriana is a professional company that makes chocolate for many well-known, outside of Ecuador, Ecuadorian chocolate brands.

Brand Impression and Label Claims

To’ak have no need to be disingenuous or hyperbolic in their communications given the totality of what they actually do accomplish. And so I am disappointed in this disconnect between brand promise and they ways in which they communicate around them on their labels and in their email marketing. This is especially true because most people have neither the background, the inclination, nor the time to research the claims.

The Unboxing Experience

The outside of the box, front and back, and the feel of the box and paper form a very solid first impression: you are holding in your hands a luxuriously-packaged bar of bar. The box itself is substantial, there is gold foil printing on the box, and there is an outer gold ribbon/wrap element, and there are lots of words that communicate around provenance.

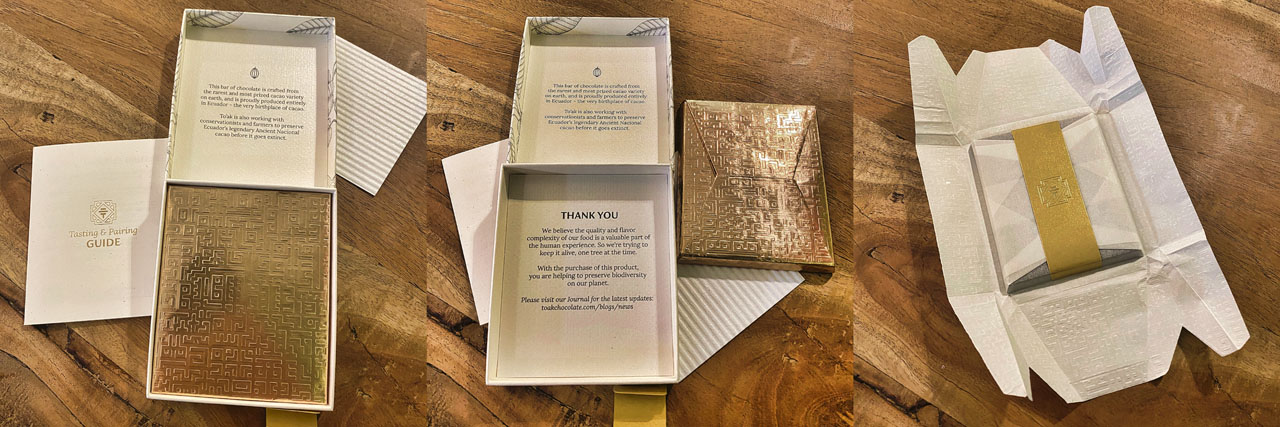

It is in these two photos that I first noticed what I have come to think of as the sustainability paradox. As I worked on the unboxing and unwrapping I started counting the number of individual elements involved with the packaging, and ended up with at least 10 distinct elements:

- The box lid that is printed and hot stamped with gold foil

- The box base with printed label attached

- The gold ribbon/wrap that is attached to the base and wraps around the front

- The “tear here” sticker (3 and 4 might be one element)

- The back label

- A piece of tape that acts as a hinge keeping the lid and base together

- A corrugated pad

- A multi-page tasting/pairing guide

- The outer gold foiled paper wrap for the bar

- An inner gold ribbon around the inner wrap, AND

- The inner paper wrap

Looking at the labels on the inner base and on the back there is no mention of any sustainability certification with respect to any of the materials used in the packaging. None of the paper elements is identified as being FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certified. To me, this seems like a huge oversight in sourcing with respect to brand promises.

There is also obviously a lot of labor going into the packaging here. Some of that could be automated (the paper wrap for the bar and the foiled paper outer wrap appear to be machine folded – more on that later), but a lot of the rest looks like it’s done by hand. At this point I can’t help but wonder even more how much of the retail price of the bar is wrapped up [again, pardon the pun] in the cost of materials and labor associated with the packaging.

The first two images (l to r) in the composite below show the presentation of the bar once everything has been unwrapped. As you can see in the left image, the bar arrived intact (I freaking hope so given everything I had to go through to get to this point). The middle photo shows what happens when you try to break off a small piece from the corner, even with a serrated knife. The bar breaks in unexpected places. While I do enjoy some interesting geometry in molds I really do prefer molds that encourage breaks into evenly-sized pieces for sharing. Surprisingly few manufacturers think about this aspect of the experience of eating their bars. The bar itself was also scuffed and there is evidence the mold was slightly underfilled and the chocolate crept up the sides creating a lip. Definitely not what I would expect for a bar priced at this level. The small details add up.

The final (rightmost) image in the composite above shows just how ill-thought out the entire reboxing process was thought out – if it was thought out at all. It’s what leads me to believe the two inner wrappers are machine folded or at the very least machine creased. Despite a lot of diligence and care it turned out to be impossible for me to rewrap the inner wrap tightly enough to accept the band neatly and then to neatly fold the outer foiled paper wrap around that and then get it to fit back in the box.

Unboxing Impressions

Despite all the care and attention that went into designing and producing the packaging, the really quite enticing layered unveiling process/experience, and the labor that went into putting everything together, the packaging is ultimately a failure for me because once you open the (figurative) Pandora’s box you can’t put the chocolate back.

Tasting/Pairing Impressions

Tasting notes are printed on the gold band outer wrap element. The packaging includes a small tasting/pairing pamphlet, and I assume that all of the bars packaged this way also come with a similar guide.

While the chocolate is technically well made I thought the printed tasting notes (which, in my normal fashion, I paid attention to only after tasting the chocolate) kinda sorta reflected what I tasted in hindsight.

My overall impression of the chocolate is that it is one you really want to eat on its own. The chocolate is quite delicate, making it difficult to pair without being overwhelmed.

In the case of this particular bar, for me, the chocolate considered on its own is not worth the price of admission. I did not find anything particularly special about the chocolate itself. It’s not one I would likely seek out – for myself. And I would not seek it out for gifting unless I knew for certain the recipient was already a fan of the brand.

Of course, YMMV. You might think this a truly excellent tasting chocolate, and that’s one of the truly interesting things about chocolate – that two people can taste exactly the same thing and come away with wildly different impressions.

Conclusions and the Quest For the $100 Chocolate Bar

For well over a decade, I have been promoting the idea that one thing the world of specialty/craft chocolate desperately needs is a $100 bar of chocolate, one in which the consensus is that the chocolate considered solely on its own merits is worth the price.

Fun (?) fact: In the late 1990s I was involved in a luxury watch promotion project. During the roughly two years I was working on this, which included a trip to the Basel Watch Fair, I learned that roughly 50% of the retail price of most luxury Swiss watch brands went to cover the costs of advertising, marketing, and sales. In other words, if you spent $10,000 on a Breguet, Patek Philippe, Rolex, or other brand, about $5000 of what you spent covered the cost of convincing you to spend that much on a watch.

When it comes to the more expensive bars aged in used casks and packaged in wooden boxes with wooden tweezers I am less convinced about the relative value and merits of the chocolate itself. (I don’t know from personal tasting experience, To’ak have never invited me to taste any of their chocolates so I cannot comment on it.)

I also wonder to what extent confirmation bias takes over in evaluating the chocolate? To what extent would I be influenced to convince myself it was worth having spent €300+ for a 50gr bar of chocolate? Would I be reluctant to admit it was not worth it – to myself or others? I think it is impossible to rule this possibility out.

Having reached these conclusions, I think the work To’ak is doing to push the upper boundaries of chocolate as a luxury food product is valuable. They promote the importance of quality cacao, paying farmers above-market prices, creating quality products with luxury packaging, connecting chocolate with luxury spirits, and emphasizing the totality of experience from holding the box in your hands to unwrapping it, to the reveal of the bar with the cocoa bean inside, and more.

It’s just a shame, IMO, they find the need to use so much hyperbolic language.

What are your thoughts? If your experience rewrapping/boxing a To’ak bar is different, please let us know. Have you tasted this bar – or other To’ak bars? Let us know in the comments.

Filed under: #barreview #toak #ecuador #nacional #unboxing

On December 1, 2020 I received the following statement in an email from one of the founders of To’ak:

P.S. Regarding the paper. The foil used to wrap our mini bars is 100% compostable. Our presentation boxes and brochures are printed on recycled paper that is FSC certified and free of chlorine and heavy metals. And our timber is sourced from certified renewable timber in Ecuador.

I did not see any of this information on the packaging materials for the box I unwrapped in February.