Peering Through a Ruby-Colored Fog

In the two weeks since I posted my first story about Callebaut’s new Ruby chocolate (And Ruby Makes Four – a New Flavor and Color Join the Chocolate Family) – there has been a lot of chatter and controversy globally surrounding Ruby – what it is, what it isn’t, how it’s made, and more. Most of the words have been written by people who were not at the launch and who have not tasted Ruby. I was there. I have. And following is a roundup of questions and answers to some of the more common questions, plus some opinions and needed perspective.

Disclaimer

I did overlook to mention, in my original post, that Barry Callebaut covered the cost of airfare and hotel to attend the launch. I did not mention this because I did not think it was relevant; those who know me know I am not going to sell my integrity and the reputation I’ve worked hard to build over the past 20+ years. I did not receive any cash compensation (quite the opposite – I spent hundreds of dollar out of pocket to secure the required visa and on out-of-pocket travel expenses), and at no point did Barry Callebaut ask that I cover the launch in any particular light. The opinions presented are my own.

Is Ruby really chocolate?

In the EU, Ruby can be classified as “couverture chocolate,” according to Oliver Nieburg, who writes for Confectionery News and who also was present at the launch in Shanghai.

The Ruby recipe sampled in Shanghai will likely be declared as a milk chocolate couverture with citric acid declared as an ingredient, according to a Callebaut representative.

However, in the US, Ruby does not conform to any of the Standards of Identity (SOI) for chocolate as set forth in CFR 21.163. I reported otherwise in my original article.

This was because of an incomplete understanding on my part. Ruby does meet the standards of identity for chocolate in some markets, including Japan, China, and South Korea. But not the US, which—ironically to some—has stricter regulations than other jurisdictions.

The reason that Ruby cannot be called chocolate in the US, it was explained by a Callebaut rep, is that residual levels of citric acid used in post-harvest processing to preserve the Ruby color and flavor are higher than allowed as an ingredient in sweet, milk, or white chocolate.

White chocolate was not legally chocolate until 2004. Industry petitioned the FDA to establish the standard in 1997 as a way to reduce consumer confusion. The standard was agreed upon in 2002 and came into effect on Jan 1, 2004. Prior to the SOI, companies who wanted to call their products “white chocolate” had to file what are termed Temporary Marketing Permits with the FDA and this is almost certainly what Callebaut will do until an SOI for Ruby can be codified. A formal SOI is important because it will reduce consumer confusion – which is the same reason the FDA agreed to the SOI for white chocolate. Information about the FDA process for establishing white chocolate as a category can be found here, and labeling guidance can be found here.

Does Ruby taste like chocolate?

Why is there an expectation at all that a Ruby-colored chocolate taste like cocoa?

Sweet chocolate (it’s important here to point out there is no legal definition for dark chocolate), *which encompasses both bittersweet and semi-sweet—*and there is no formal distinction between the two—has the expectation that it taste the most chocolatey. Our expectation is that milk chocolate will taste less chocolatey than dark, and white chocolate will not taste chocolatey at all.

Following this progression, why is there any expectation that a Ruby-colored chocolate will taste like a dark chocolate? It’s kind of the point that it doesn’t.

What are Ruby beans? Are they a special variety?

Ruby beans, which grow in West Arica and South America, among other places, are not a distinct, distinguishable, genetic variety.

Ruby is the name Callebaut gives to beans that contain chemical compounds that occur naturally in all cocoa beans that in Ruby beans occur in a specific ratio and above a minimum level. When processed in a certain way, the beans retain the Ruby color and flavor all the way through to the finished chocolate.

Ruby is not positioned as a “fine” chocolate made using fine flavor cocoa beans in the sense cacao fino y de aroma is used. The expectations the “fine chocolate market” have for Ruby—and the assumptions they are making —should not come from the same place as cacao fino and fine chocolate expectations.

Ruby is a different product, created for and aimed at meeting the needs of markets with needs that are not met by other chocolates, including craft chocolate.

That said, Callebaut—in hindsight—did make mistakes in the way they communicated about the beans, unnecessarily causing confusion.

Are Ruby beans GMO?

Ruby beans are not GMO. As explained above, Ruby beans are conventional beans with a specific chemical makeup.

Is Ruby processed with odious chemicals?

I asked this question directly to a senior Callebaut exec who said that the Ruby that we tasted was not processed with odious chemicals.

There is a patent covering part of the Ruby process [ This is also something I misreported in my original article. ], and this patent does mention using chemicals – chemicals that are used in many industrial cocoa processes.

The reason they are mentioned in the patent is that’s the way patents need to be written. If there are three ways to do essentially the same thing (say, remove cocoa butter to create a defatted cocoa powder), the patent must mention all three and indicate one is preferable (sometimes referred to as the preferred embodiment). If the patent only mentioned one way to achieve an effect then someone could use any of the other known ways to get around the patent. Just because the use of chemicals is mentioned it does not necessarily follow that those chemicals are used.

According to the patent, the wet beans are processed in an acidified environment. The acid used for this is citric acid. This is the acid commonly found in citrus and other fruits and is what gives sour candies their sour flavor. Citric acid is completely safe to consume, even in pretty large quantities. Research also indicated that citric acid did not have any negative connotations with consumers.

Why is Callebaut being so secretive about the process?

I discussed this with some intellectual property (IP) experts who told me that the multipart strategy Callebaut is pursuing makes sense given the current state of IP law. A patent protects some parts of the process and other aspects are being protected as trade secrets The use of trade secrets is common – Coca Cola protects the formula for Coke syrup as a trade secret; KFC protects the recipe for its seasoning and breading mixture this way.

Patents have a limited run and once the patent expires other companies will be free to introduce their own Ruby chocolates … assuming they can reverse engineer the trade secret part of the process.

In this respect, it’s important to keep in mind that Callebaut is a publicly-traded company. Therefore they have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize shareholder return. The patent and trade secret strategy is a part of that fiduciary responsibility. You may not like it, and you may not agree with it, and it does go against a lot of the openness that is characteristic of the craft chocolate movement, but it’s a fact of business for a global company like Callebaut that cannot be overlooked.

From an IP perspective, the fact Callebaut did not trademark Ruby is a strong indication that they are very serious in their desire for Ruby to become a generic term, just as kleenex and xerox now are, and as google may soon become. That’s going to be a good thing for the industry overall though navigating it is going to be a challenge. In talking with people who know about such things this may be the first time that a global company has created a new category in any industry and given the category name away.

Is Ruby truly innovative?

There are many people who have take a look at the patent and gone, “What’s innovative about Ruby? It’s obvious! Of course if you do X and Y, Z will happen. There’s nothing new here.”

But that’s the nature of a lot of innovation—doing things that are obvious, in hindsight. There are many steps to the Ruby process, from identifying that the beans exist in the first place, to understanding what class of chemicals is responsible for the phenomenon, to figuring out industrial-scale processes that can enhance and preserve the flavor and color in a finished chocolate so that it can be brought to market.

Another aspect of this innovation that I think that is being overlooked is color-blindness, or at least the narrow focus on brown as the primary desirable color for fermented cocoa beans to make “good chocolate.” Brown is the signifier of chocolate flavor in fermented beans. It takes a pretty huge imaginative leap to focus on a color other than brown and on un- or under-fermented beans as under-fermentation is considered to be a defect and highly undesirable in most, but certainly not all, cultures and applications.

What is the future for Ruby?

When Nestlé introduced white chocolate in the late 1930s – the Galak aka Milkybar – it existed as a category of one example.

Today, white chocolate consists of hundreds of different examples and variations; white chocolates made with undeodorized cocoa butter—which can have a lot of chocolate taste, white chocolate made with goat’s and other non-dairy milks, and white chocolates with exotic flavorings and inclusions. That list does not include pastry, bakery, and dairy products made with white chocolate.

History shows quite clearly that the introduction of a new product or category can spark a period of experimentation and there is no way to guess what where that experimentation will lead. Pastry chefs and confectioners are, as a group, wildly creative people and I have no doubt that there will be many very interesting things done with Ruby. That is one major reason for my excitement for a future of chocolate that has Ruby in it.

It’s also important to keep in mind that white chocolate, from its humble beginnings as a category of one in the 1930s, is forecast to reach ~US$17.5 BILLION in sales in 2017. It was pointed out in the article in Confectionery News that the market for fruity (i.e., fruit-flavored) chocolate is only 2-3% of the market. But that’s still $2-3 billion dollars. That’s the historical context I am thinking about when I look at Ruby. Today, Ruby is a new category with only one example. Who knows what Ruby can achieve in 80 years? A lot, I believe.

Do I like Ruby?

This is a question I have been asked a lot and for many it seems to be the million–dollar question.

I feel compelled to preface my comments on this topic by pointing out that I have been eating, thinking about, rating, judging, and reviewing chocolate for close to two decades, With all that experience, it’s become easier for me to separate out objective aspects of the chocolate I am tasting (e.g., is it will made), from subjective aspects (i.e., do I like it).

I am an equal-opportunity chocolate fan; I prefer to taste first and judge after and will give any chocolate an opportunity to impress or disappoint. When I am tasting professionally I will taste anything and everything put in front of me, and I enjoy (unlike many others), if not prefer, judging the flavored white chocolate bar category and bonbon categories in competitions.

The truthful answer is that I don’t dislike Ruby and I would not turn it down if offered. However, it would probably not be my first choice if presented with an array of chocolates from which to choose.

When eating chocolate recreationally, I gravitate towards dark milk chocolates, especially 5 5% and above. For me, a good dark milk chocolate combines the flavor intensity of a darker sweet chocolate with the creaminess and melt/mouthfeel of a milk chocolate and, because lactose is not as sweet as sugar, at any given percentage the dark milk will usually seem less sweet than a sweet chocolate of the same percentage.

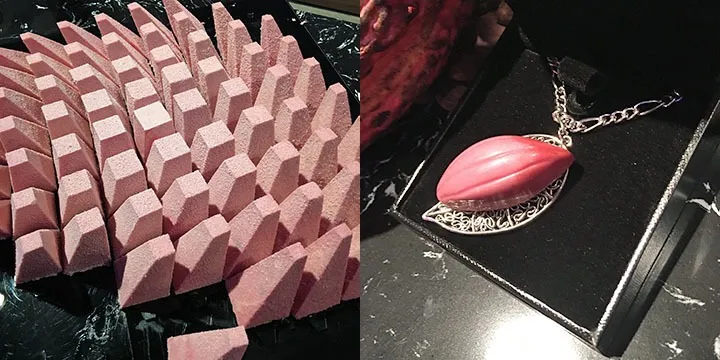

The Ruby I have tasted shared some of those characteristics, especially not seeming as sweet as I expected. It had the melt and mouthfeel of a well made milk chocolate. I don’t miss the lack of chocolate flavor (though there is a faint hint as it passed under the nose as it enters the mouth) because the red berry flavor is satisfying, though the finish is short. The short finish makes it easy to reach for another piece—Ruby is eminently snackable. The Ruby–panned fruit and nut items I have tried (you can see some of those in the photo of the Ruby pod) were all remarkable.

I also feel compelled to say that, quite frankly, I would choose Ruby over many chocolates I have tasted that won awards in the International Chocolate Awards, the Academy of Chocolate awards, the Good Food awards, and/or the Northwest Chocolate Festival awards, to name just a few awards programs. Though award-winners, I quickly tire of chocolates made from the same beans on the same equipment according to the same basic recipe, and that exhibit hard breaks, tough melts, and gritty textures—even if there are some interesting flavors in them.

I do appreciate Ruby for what it is, and I understand completely why people who say they like it, like it. The color matches the flavor. It’s bright and refreshing. It is not a challenging chocolate that’s hard to like or appreciate, and it doesn’t require any special understanding to enjoy.

[ Author’s note – edited on 9/21 to fix typos, punctuation, and grammar, to expand upon a point around bean naming, and to add a photo.]

JD – The concepts of patenting and trade secrets are not related in the way you describe. Ideas covered by patents cannot also be treated as trade secrets. They can’t overlap.

In order to obtain a patent you must disclose what you are doing and how. This is so someone can determine if what you’re trying to patent is, in fact, eligible to be patented. One reason something might not be patentable is that there is prior art that shows that this is not new, not uniquely different. Publishing the method also gives others notice, and can spur invention on to try to find other ways to do the same or similar things in different ways. In return for this disclosure companies are given the exclusive rights to commercialize the patent for a limited period of time. One commercialization option is to license the patent to some other entity for cash. Importantly, patent protection enables enables the holder of the patent to sue anyone who uses the patented subject matter without securing a license first.

Trade secrets, on the other hand, rely on complete non-disclosure, or security through obscurity. One way trade secrets are protected is through NDAs. This approach fails if, somehow, the secret is stolen and/or leaked. While there may be some legal recourse against a person who had a valid NDA revealing the information, there is no mechanism in law to pursue a third party using the information. Let’s say someone stole and published that certain secret recipe of eleven herbs and spices. If an employee with an NDA stole and leaked the recipe the company could sue the employee, especially if the employee was profiting from the release of the info. If the employee distributed it for free by posting it on Reddit the genie is out of the bottle and the recipe is no longer secret.

Barry Callebaut patented the post-harvest portion of the process they go through to make Ruby chocolate. This covers the ways beans can be fermented (or not) to keep them from oxidizing and turning brown.

Separately, Barry Callebaut treats the manufacturing processes as trade secrets. Once the beans arrive at the factory there is the need to keep them from oxidizing and turning brown during all of the manufacturing processes. This is not a trivial problem. I would guess there is little to no roasting and temperatures are kept as low as possible. I don’t know exactly, of course, and that’s the point.

So patents and trade secrets don’t overlap in this case.

I’m very late to the party here, but still quite puzzled. My understanding of patent law in the US is that it gives a period of time during which you are the exclusive licensor of the invention, and in exchange you describe the invention in sufficient detail that a person skilled in the art should be able to duplicate the invention.

So how can they patent it AND reserve part of the knowledge as a trade secret? It seems the quid pro quo between inventor and society at the heart of a patent is subverted.

The neat thing about this technology isn’t the color, in my opinion, it’s the flavor. They’e implemented it in a way that focuses on the color – but literally the same approach can be used to direct flavor. Now, being a bit of a purist i personally tend to favor that which is the least processed, even if that means that it comes with some imperfections from time to time – but i do think this is a novel application of technology. We’ll see if consumers think it’s interesting or not. One of the very large CPG companies was given the opportunity to commercialize this years ago and passed on it.

In the short term, I think BC’s goal is to provide an open playing field for their customers who will be using ruby as a way of reducing market confusion. As the purpose for making the trademark generic, it should be possible for anyone to create a product that has the same flavor and color profiles by flavoring it and coloring it and calling it ruby. However, the ingredients list would have to include those flavorings and colorings so consumers might not be all that keen on it. Valrhona wanted to create a category around blonde chocolate, which was actually just flavored white chocolate, and there is no good natural flavor association in food with the color blonde.

BC are likely to be aggressive in protecting ruby if someone were to try to reverse engineer it and get around the patents. Once the patents have expired then I can see the possibility (likelihood) of companies coming in with competing versions of ruby, assuming that ruby is successful in the marketplace in the interim.

Also – the FDA would allow the use of a term like “ruby chocolate” with a temporary marketing permit – so maybe a trademark would be okay in that context. Again, IANATL.

The question is moot because Callebaut have decided not to trademark the term. Having spent quite a bit of time talking with Callebaut reps on this specific topic, I don’t see it as a strategy to avoid rejection of their trademark application here in the US. I think it’s part of a long-term (>15 years) approach to the product and the market.