TheChocolateLife::LIVE – How I Learned To Taste ... Anything & Everything

OR: How I approached training my palate on my journey to becoming a professional chocolate critic. Streaming worldwide on Tuesday, August 23rd, from 12:00 EDT.

Prolog

I had my entrepreneurial epiphany to become the world’s first professional chocolate critic back in March, 1994. (Professional in the sense that I thought of it as a business, not a hobby.) This was a very long time before there were any formal chocolate tasting training programs.

At the time, there were many programs for learning to taste wine to become a professional sommelier or critic. About this time there was an uptick in interest in both coffee and beer. But we’d have to wait until the mid-2010s for their to be the first credible organized training programs for chocolate.

I struggled for more than five years to develop a rating system for chocolate that was not based on some other food or beverage. In fact, I waited until I had one I was happy with before I officially launched chocophile.com in May, 2001. In the end, my rating system did not involve arriving at a unique number/score/grade on a 1-10 or 1-100 scale. Instead, my rating system focused on value and was comprised of three components:

- Price. Market research reports at the time divided the market into Mass Market (under $15/lb), Mass Market Premium ($15-25/lb), and Gourmet (over $25/lb). I modified this to accommodate more expensive products, adding a Prestige category and adjusting the price points for Gourmet.

- Style. In my research and experience, I identified three unique styles of chocolate – Northern European, Southern European, and American. These were based on stereotypical flavor profiles. Northern European (Belgium, Switzerland) style was lighter and sweeter than Southern European (France, Spain, Italy) style. I soon added another category, Nouvelle-American, which combined elements of the American style with French approaches and techniques. The style quickly communicated overall expectations for flavor and other, technical, aspects. Again, these were styles, and the company did not actually have to be located in a mentioned region to produce chocolate in that style.

- Rating. I decided on a seven-point scale. The bottom rung was Bad and the top rung was Extraordinary. The inbetween steps – from the bottom up – were Poor, Ordinary (much more damning than Average; I spent a long time thinking about that difference), Good, Very Good, and Superior.

In use, reviews would include all three elements, often with a description of the company as a whole and descriptions of individual products. The idea was that, for any given product, what value did it deliver for the price paid? A piece that might have been awarded a high value at one price point might only deliver a lower value at a higher price point.

I am Still Only Part Way There ...

I was fortunate in 1998 to start working for Pierrick Chouard of Vintage Chocolates, then the exclusive importer for Michel Cluizel and Domori in the US. Over the course of the next five years or so I sold chocolate into some of the most demanding hotel and restaurant kitchens in Manhattan and beyond. It is through my interactions with chefs that I learned what they were looking for and how to communicate with them about chocolate.

While arriving at a rating system was just one aspect of my journey to becoming a chocolate critic, I still had to figure out how to evaluate what I was tasting and put it into a linguistic framework. And, I felt it was important that the framework had to respect the simple fact that eating chocolate is different from drinking wine, beer, spirits, coffee, etc. It did want it to be a simple translation from wine, and I wanted a system that did not require a calculator.

The Breakthrough

Most evaluation systems are what I have come to refer to as Descriptive. They are focused on developing a person’s taste memory through exposure and repetition so that when something is tasted it can be identified. Component flavors and aromas are recalled and clearly articulated. Descriptive tasting relies on the fact that it is necessary to have an actual referent, i.e., you must have tasted something before and committed it to memory, in order for you to be able to identify and recall it. If you’ve never tasted jabuticaba then you’ll never be able to identify it without prompting.

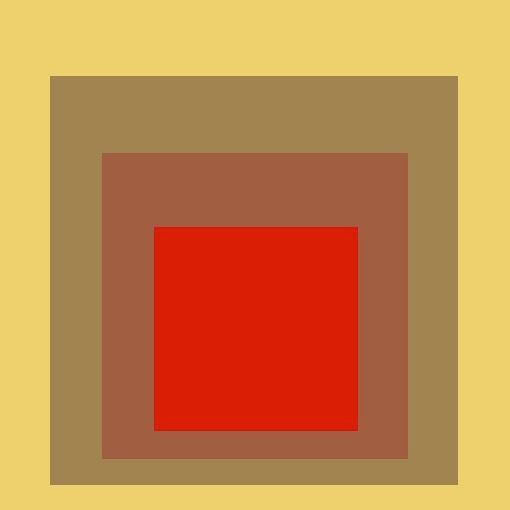

Enter the work of the painter Josef Albers and his series, Homage to the Square. I had encountered Albers’ work as a student at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design), where I earned a BFA in Photography in the early 1980s. This series of Albers’ explored the idea of simultaneous contrast, the idea that the juxtaposition of colors affects our perception of those colors: change one and the perception of all of the surrounding colors changes.

Does anyone else remember the smell of Color-Aid paper and paint – and not necessarily in a good way?

I had the pleasure of touring the house/studio/musuem of Luis Barragan when in Mexico City in 2019 and was able to put my nose within an inch of an original Albers canvas – no glass, no ropes, and because of my guide, no guard to tell me to keep away. It was a breathtaking moment to be that close and see weave of the canvas and the techniques Albers employed to apply the colors to it.

Digression

Upon reflection, it turns out I had been introduced to the concept of simultaneous contrast in 1980 by the acclaimed nature/wildlife painter Jan Janosik, whom I met and befriended while I was living in Portland, OR. I remember vividly (still, after more than 40 years) being on a group picnic in the Oregon countryside one late-Spring day. I don’t remember the precise context, but at one point Jon pointed to a tree and the sky, saying to me, “The leaves are the color green they are because of the blue of the sky behind them. Change the color of the sky, and the green of the leaves will change ... and vice versa.”

These two experiences form the basis of how I trained my palate, a process I now call Comparative (as opposed to descriptive) Tasting. This approach also informs how I give tasting and pairing classes.

The underlying concept is that the human nervous system is built to compare things. This car is closer than that one. My shirt is bluer than your shirt. This peach is sweeter than that one. And so on. We make these comparisons all the time, every day, without ever stopping to thinking about how we do it, let alone that we are doing it. And we don’t need any special training; millions of years of evolution have given our nervous system these innate capabilities. We do it naturally, reflexively, unconsciously.

And, it turns out, chefs rely on simultaneous contrast too, not just painters, photographers, musicians, and other artists.

Chefs adjust levels of salt, acid, sour, sweet, bitterness, and other components of their recipes to achieve specific results. Too much acid can hide a flavor; reducing the acid lets that flavor shine through or in some circumstances enhance another taste component. It’s also true that the order we taste things affects our perception of the flavors, as do the textures – and especially the fat melting points – of what we’re eating.

The Comparative Tasting Method relies on the fact that everyone can taste two pieces of (for example) chocolate – the concept is not limited to chocolate – and make simple comparative evaluations:

- This chocolate smells/tastes sweeter than that one.

- This chocolate melts more easily than that one.

- This chocolate smells/tastes burnt while that one does not.

In this live stream we will explore my Comparative Tasting Method in depth, using two different exercises I developed.

After the live stream is over I will be uploading tasting mats I produced for each of the two methods. The download links will be directly below.

A Closing Note

I think the Comparative approach is more useful and productive than the Descriptive approach for the vast majority of people because its primary focus is on understanding what a person likes – and why they like it. This is an aspect of learning to taste that I recognize as being incredibly important, if not the most important thing, and is one that is largely overlooked in Descriptive tasting curricula.

Resources

Cocoa of Excellence Flavor Wheel (link to .PDF)

Cocoa of Excellence Glossary (link to .PDF)

Cocoa of Excellence Sensory Evaluation Form (link to .PDF)

Live Stream Links

Watch/Participate on YouTube, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

My LinkedIn profile

TheChocolateLife page on Facebook

The Seven Levels of My Original Rating System in Detail

This is the original rating system from chocophile.com It has evolved, a lot, since then. I have made it simpler and started using emotive language designed to convey what I feel about a chocolate, not what I think about it. I had to refrain from editing the language in any way – this following is just as I wrote it 20 years ago.

- E / Extraordinary: The quality of the chocolate is transcendent; 96+ on a 100 point scale. Who cares what it costs?!

- S / Superior: The chocolate is among the best of its kind; 90-95 on a 100 point scale, and/or offers extremely good quality for the price.

- VG / Very Good: The chocolate is much better than average with a small number of minor flaws and/or is a better than average value for the price. 80-89 on a 100 point scale.

- G / Good: The chocolate is better than average and/or represents a good value for the price. 70-79 on a 100 point scale.

- O / Ordinary: The chocolate is average, there is nothing special about it, and/or is of only average quality for the price. 60-69 on a 100 point scale.

- P / Poor: The chocolate is edible, but barely, and/or is of low quality for the price. 50-59 on a 100 point scale.

- B / Bad: The chocolate is basically inedible. 49 or less on a 100 point scale.

Some Closing Thoughts

The Comparative Tasting method is by no means the only way to learn to train your palate. Is it the best way? Maybe, maybe not. YMMV – because it’s a different way to approach the issues involved, with different initial starting goals. What is it about what you’re tasting do your like? Why do you like what you like? How do you use this understanding to develop confidence in your palate and communicate that confidence to others?

One way in which I do believe that the Comparative Tasting method is more useful than other approaches is that the approach is applicable to a wide range of foods and beverages as well as to understanding pairings – without any modification or special training.

Let us know in the comments, below.