Review: Ridgewood Chocolate

While there may be no wrong ways to make chocolate, are all ways to make chocolate “right?” [Edited for grammar, punctuation, and clarity.]

Preface

I struggled with how many words (over 2500 ) I was typing and the time I was spending on this review.

In the end, I decided it would be informative if I published this extended review explaining more of my process.

In general, my primary goals in any review are to examine the following points:

- Is what I am tasting well made?

- Is what I am tasting a good exemplar of its kind/type?

- And, finally, “Do I like it?”

But other aspects of reviewing are a part of my unboxing-unwrapping-review process, and that includes a look at a company’s website. I (now) go through this extended evaluation process for all of the products – there’s more to the process than just sharing my impressions of the tasting experience.

I research:

- Why is the company making chocolate in the first place?

- What are their motivations and what are they trying to achieve?

- How are these ideas expressed online and on the packaging/wrappers?

While I am (eventually) going to get to the first three questions, the first part of this review will cover the second set of questions.

Some Backstory

Back in 2018, I was approached by Constantine K, one of the proprietors of Ridgewood Chocolate, asking me for my opinion about something he wrote on the conching process.

More recently, I learned that something I said (roughly, “There is no right or wrong way to make chocolate”) was being attributed to me in some of their materials, but incompletely.

I have said something like that in the past – there are hundreds of hundreds of different ways to make chocolate and none of them is, on its face, “wrong” in the sense you wouldn’t end up with chocolate in the end.

I think the questions are not whether a process is intrinsically right (good) or wrong (bad), they’re:

- “Is the chocolate that is the result of any particular process any good?” (Is the chocolate well made – a technical evaluation.)

- “Does it taste any good?” (And the corollary, “Do I like it?”)

- “Is the process efficient enough that a sustainable business can be created using it?” (Businesses should emphasize being sustainable as businesses.)

As I have said and written widely and often, there is no single objective standard for quality – the concept of quality comprises a basket of attributes and each of us values the attributes in that basket differently.

For some, taste is the most important attribute. For others, texture, or price, or genetics, or a technical characteristic such as free fatty acid levels is valued most highly. For others it might be around the ethics of production of the cocoa they source. There are many aspects to quality that can be considered, including the potential health benefits of cocoa and the way it is (and is not) processed into chocolate.

In the process of my recent correspondence with Constantine I asked for a sampling of 3-4 bars, in part to provide feedback (after taking a look at the way the chocolate was described and sold on the website), in part as a way of exploring the idea that there is no wrong way to make chocolate, and in part to examine their claim:

“Every step, a genius in culinary acumen ... analyzing infinite permutations to deliver a unique chocolate taste ... Five pounds at a time.

Nobody we know makes chocolate like this ... Literally like no chocolate bar you've ever tasted in your life.”

Unboxing and Decoding

While it’s never a good idea to judge a book by its cover – and by analogy, a bar of chocolate by its label – one question we can ask is if the label reflects what the bar costs and if the label is a reliable indicator of what will be found inside.

Ridgewood’s bars nominally weigh one ounce (28 grams) – more on that later – and are priced at $10/ea.

There is also some interesting (in the sense it calls attention to itself because it is not common) language on the front of the bars: Shelling, Oxi(dation), T/H (not sure what that refers to), and Size.

On the backs of some labels, I noticed that the ingredient list is incomplete, as the bars with nuts in them do not list nuts as an ingredient, and the bars with salt in them do not list salt as an ingredient. The nutrition panels list 0 (zero) grams of sodium for all the bars so my guess is that the “nutrition facts” do not include the salt or the nuts. This is problematic for many reasons, as are the incomplete allergen statements.

Unwrapping and Decoding

The labels appear to be printed in-house and cut (irregularly) by hand. They are then folded and glued. The glue was applied in such a way as to require careful manipulation with a knife to separate the paper label from the inner foil wrap without tearing it.

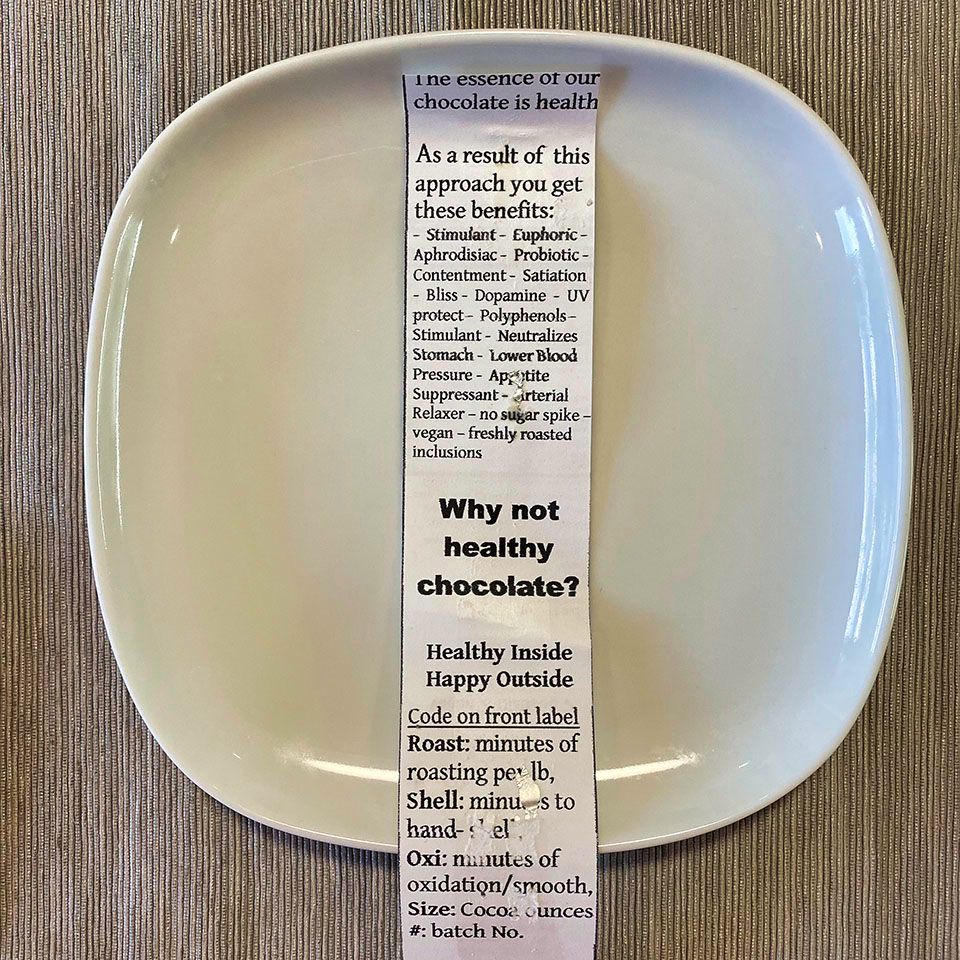

The information on how to decode the information on the front of the bar is on the inside of the label:

- Roast: length of the roast, per pound, in minutes – a very non-standard way to think about and report this metric.

- Shelling/Shelling/Shl: number of minutes required to hand-peel the beans – not sure why the consumer might find this important.

- Oxidation/Oxi: a non-standard way to refer to the conching process.

- T/H (plain bar): not explained on the inner label.

- Size: weight of cocoa nibs in the batch.

The data, presented in this way, is slightly confusing (in addition to being incomplete). Looking through product descriptions on the website:

“Bean to bar roasted chocolate. Every step, a genius in culinary acumen [emphasis added], employs hands-on, analyzing infinite permutations to deliver a unique chocolate taste. Five pounds at a time. Nobody we know makes chocolate like this. Seventeen hours between two people, in two days.”

Taking a look at the Almond & Sea Salt bar, it appears that the 68 ounces (4lbs 4 ozs, 1814.37 grams) is the weight of cocoa nib in the batch. If so, when we calculate for sugar, the batch size is ~5.3 pounds (~2.4kg), and if we assume a roughly 25% loss factor in roasting and shelling (to make the math easy), the roast time for this batch is on the order of 53 minutes.

Given the “Five pounds at a time. Nobody we know makes chocolate like this. Seventeen hours between two people, in two days” language from the website, Ridgewood Chocolate emphasizes small batch sizes and a lot of hands-on labor in the creation of their products.

Does this approach automagically lead to a higher-quality product? No. All it does, automagically, is increase the cost of labor priced into the chocolate.

Pre-Tasting Evaluation: Almond & Sea Salt

Before I can get to tasting, there are two important evaluation steps:

- Aroma: there is a strong cocoa aroma that is overlaid with a bright/sweet, fruity/vegetal component with a hint of underlying bitterness. What is interesting about the bright/sweet, fruity/vegetal aromas is that they disappear if the wrapper is left open for a length of time. What you’re left with is cocoa underlaid with nuttiness. The bitterness is pretty much gone, but there is a hint of brightness from the sugar.

- Look: see the photos:

L: back of the bar; R: front of the bar.

From these two photos ,I conclude that tempering and molding are uneven. The almonds appear to be mixed (incompletely) into the chocolate before the molds are filled. I don’t mind the look at all – in fact I found this the most appealing visual aspect of the bar.

L: scaling the bar; R: a closer look at the nutrition facts panel.

In this photo, you can see that this bar actually weighs a lot more than 28 grams (50% over weight). This is problematic when compared with the nutrition facts panel. One issue is the mismatch between the serving count, size, and the weight of a square. There are 20 squares in this bar, each weighing an average of 2.1 grams. 8*3.5 grams is 28 grams, not 42. The carb count and the sodium count appear not to include the almonds and salt, and – at 75% cocoa content – less than 1% added sugar in a bar made with “natural sugarcane” seems very low.

Why am I spending any time pointing these things out?

- Because one of Ridgewood Chocolate’s primary selling points is the health properties of chocolate in general and their chocolate in particular – because of the way it is made. (Visit the link below.)

- The Ingredients list and Nutritional Facts panel give incomplete and incorrect information. It looks like one ingredients list and nutrition facts panel are used for all four bars – which is bad practice.

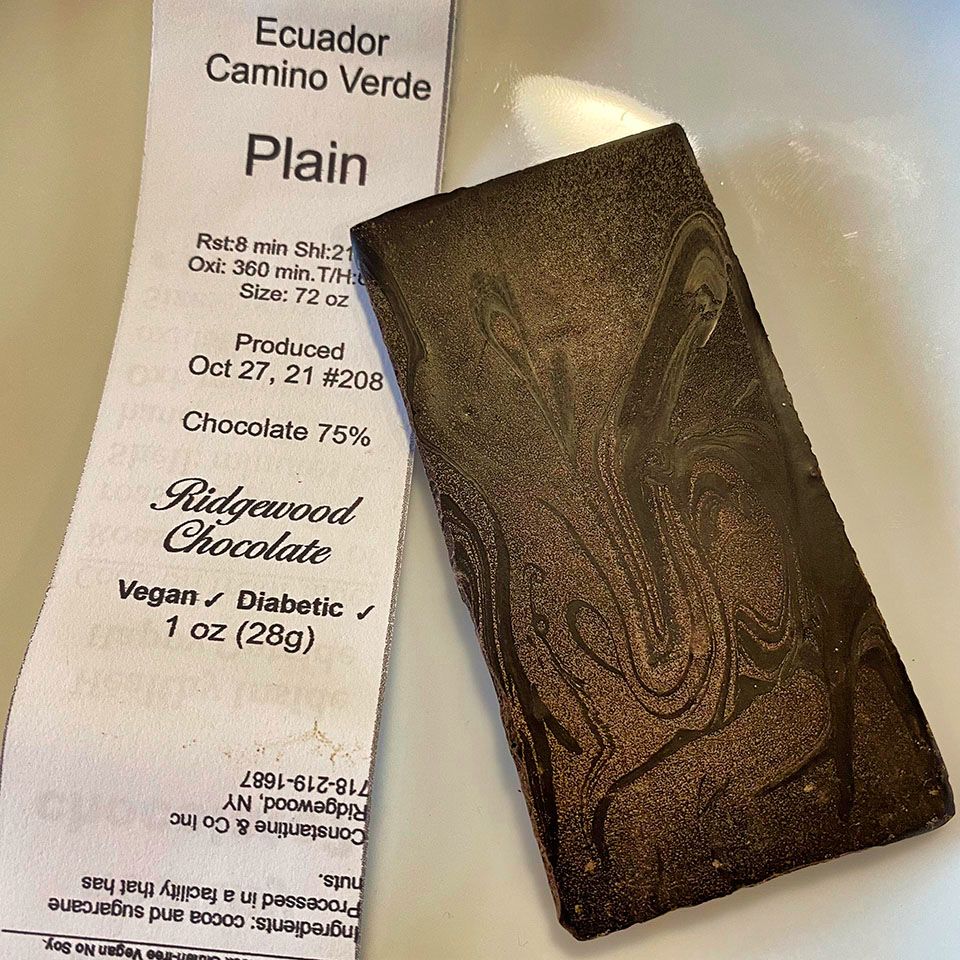

Pre-Tasting Evaluation: Plain

This bar weighed in at 35 grams, 25% over weight.

- Aroma: the cocoa aroma is present, more front and center, with the bright/sweet/fruit/vegetal aspect quite muted with the bitterness more prominent.

- Look: see the photos.

L: Back of bar, showing that though the bar is only about one month old there are some tempering issues that may affect bite, melt, and flavor release; R: The front is pretty scuffed but the pinholes that appear on the fronts of the Almond, Coconut, and Pistachio bars are missing.

Tasting Notes

Ecuador (Camino Verde) / Plain – Good snap. Slightly gritty bite and chew, easy and clean melt. The dominant flavor note upfront is the roast. There is a fleeting hint of fruity acidity with the roastiness dominating on the short/medium finish. There is a not-too-bright brightness from the sugar, and it seems like the grit on the bite/chew is from the sugar which explains the brightness. There is an earthy/vegetal quality on the long finish which gives way to the roast.

Tanzania / Almond & Sea Salt — The bright/sweet fruity/vegetal aroma note that was originally present disappeared after an hour or so and the dominant note on the nose became that of the almonds. Good snap. The bite/chew/melt is dominated by the almond inclusion. The primary taste note I detect up front is a bitterness I associate with almond skins that dominates the chocolate, and in the mix is a blast of sweetness that gives way to roast with faint notes of chocolate on the medium/long finish, giving way to hints of almond. There is a nice roundness in the mouth on the long finish dominated by the almonds (in a good way). I detect no obvious salt texture/taste in the bar, which suggests the salt was not used as an inclusion.

Ecuador (San José) / Coconut & Pink Salt — As with the Almond inclusion bar, there are some depositing artifacts (large pinholes) and bloomed areas on the back. The initial aroma reminds me of fennel seed or maybe coconut sugar in a weird way (because cane sugar is listed as the sweetener). That aroma dissipated pretty quickly to cocoa with a hint of sweet brightness. The bite/chew/melt is dominated by the coconut inclusion, and the whole profile of this bar is about the texture of the coconut more than it is about any particular flavor of coconut or chocolate or salt.

Trinidad (Bio Claro) / Pistachio & Pink Salt — As with the other two inclusion bars, the bite/chew/melt are about the inclusion, not the chocolate. Interestingly, the cocoa note is more present on the nose, absent any sugar brightness. The flavor reminds me of lightly burnt whole wheat toast; if you did not tell me there were pistachios in the bar I don’t know I would have been able to tell they were pistachios absent a very close examination of the back or the edges of a broken-off piece.

Concluding Impressions and Thoughts

At $10 for (nominally) a 28gr (1oz) bar, Ridgewood Chocolate’s offerings are comparatively expensive. (In fact, there is even one offering at $30/oz!) If the bars were true to weight, that would scale out to $160/lb or $350/kg.

Being this over weight is a bad business practice as it reduces gross sales revenue. Even so, Ridgewood Chocolate’s products are still at the upper end of the scale when it comes to price.

While priced as a luxury chocolate, the bars I was sent are not presented as luxury items.

They are presented as healthier-for-you chocolates. It is very much the case that products presented this way, especially those with a parallel pitch of hand-crafted in small batches command higher prices: A lot of hand labor is involved and so are priced in the luxury bracket.

It is also my experience that consumers who respond to healthier-for-you and hand-crafted claims tend to be more tolerant of certain classes of “defects.”

Is every step, “a genius in culinary acumen?”

Having tasted many, many, hundreds of chocolates over the past 20+ years, the fit and finish of the bars (tempering and molding alone) bely this claim as technique is part of culinary acumen. “Infinite permutations” were obviously not analyzed but this is just marketing hyperbole.

Were these bars well-made?

A visual examination says to me, “Not particularly.” But then my standards in this respect are very high. Will what I find to be below-par matter to others? Maybe not. Obviously not as Ridgewood Chocolate has been around for at least three years.

Is the way Ridgewood Chocolate makes chocolate “wrong?”

No. The way Ridgewood Chocolate chooses to make chocolate is not “wrong.”

But it is certainly not the way I would choose to make chocolate.

Their process results in a particular style/result, which is not one I personally seek out to eat on a regular basis – even though I really do enjoy salt, almonds, coconut, and pistachios in chocolate. The flavor ideas are ones I like, the execution is not to my taste and it’s not clear to me, tasting the chocolate, how the different origins used contribute to the final result.

In the final evaluation, these are not chocolates I would purchase a second time having tasted them. But then these chocolates are not made for the kind of consumer I am. When it comes to the health benefits of chocolate I prefer products that put a smile on my face. This lowers blood pressure and elevates my mood. The fact there might be chemical properties in the chocolate that also contribute to my health is a bonus.

If you are interested in, and attracted to, Ridgewood Chocolate’s marketing messages, then by all means give these a try ... and let us know your thoughts in the comments below.