What’s In a Word?

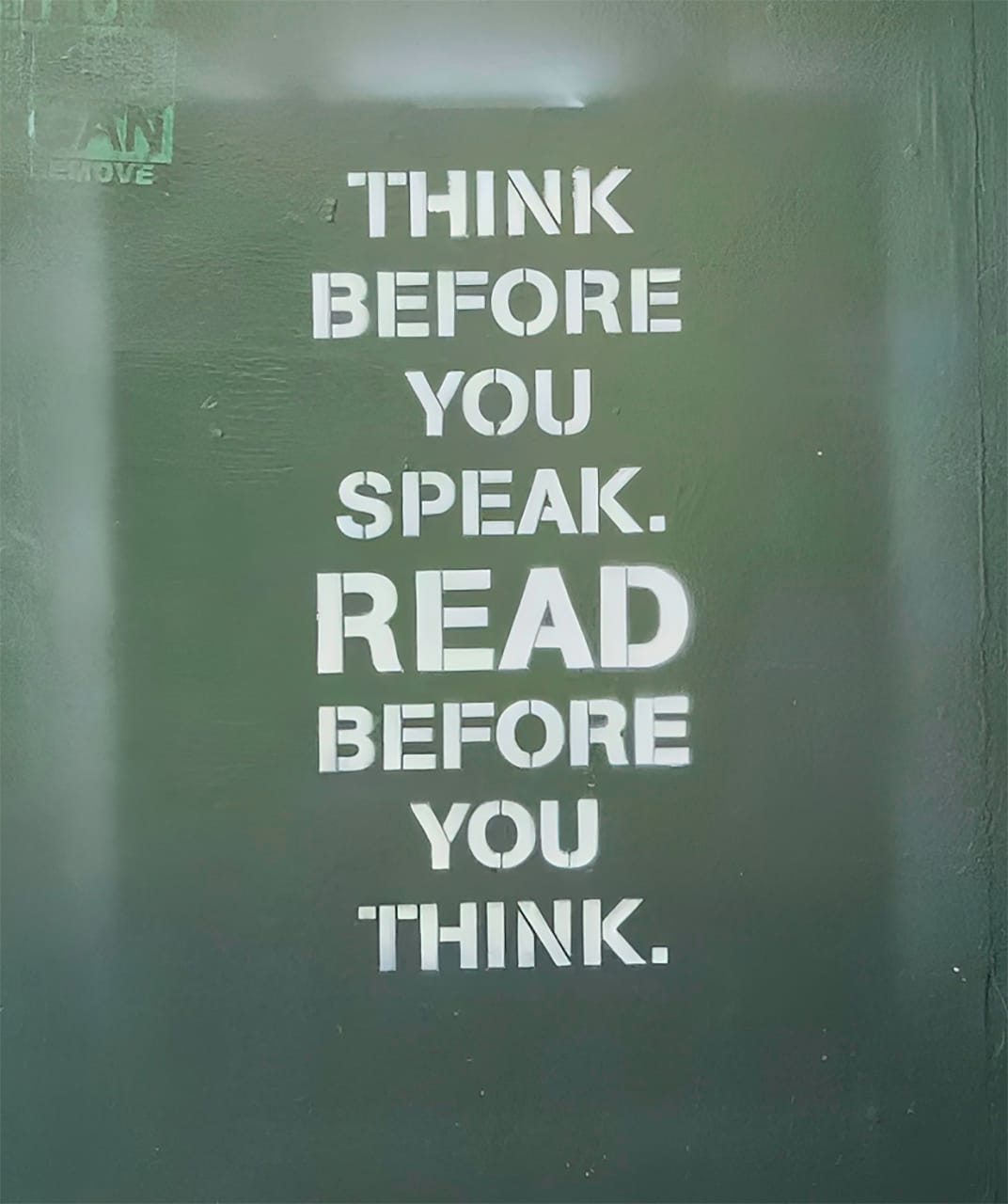

Think before you speak. READ before you think.

Dear Birgitte:

Two things we share in common, in addition to careers in high-tech and an interest in chocolate, are that we are both published authors and consider ourselves educators.

In our roles as authors and educators, we know how important our choice of words is. I have said that the words we use inform our beliefs, our beliefs inform our actions, and our actions have consequences. I am confident that we also both believe that it is important to be factually accurate and that we differentiate between facts and our analysis and opinions of those facts.

I grew up in a household of readers and my mother, in particular, was a lover of language. I have very fond memories of the word games we used to play on our summer extended car camping vacations. As we were exploring the majesty of state and national parks throughout the western states, word games were a staple tactic in the “let’s keep the kids occupied so they don’t get bored and start chanting, ‘Are we there yet?’ tool chest.”

My father was a mathematician who entered the computer industry in the mid-1950s and so I grew up in a home where curiosity about technology was encouraged. My father worked in the computer facilities at Stanford, UCI, and Victoria University in Wellington (New Zealand), so an interest in the application of technology in educational settings was just a part of my daily life and I remember my visits to the computer room at UCI and Victoria fondly. The computing technologies of the 60s and 70s have come a long ways, and I am still constantly astonished.

But, since the age of about 12, I knew I wanted to be a visual artist. When I asked about computers, my father would hand me books about programming in FORTRAN or COBOL, and the best computer graphics of the day consisted of dot-matrix printouts of Snoopy.

One way I was able to combine my love of language and technology was in my work at KBOO, a community-supported non-commercial FM radio station where I worked between my freshman year at The Evergreen State College and getting my BFA at Rhode Island School of Design. I studied for my FCC license, helped build the broadcast studio infrastructure, took classes on engineering remote recordings, spent uncounted hours on-air hosting music programs in many genres, interviewed emerging local and established world-renowned artists, and co-produced the monthly program guide. I even hosted a monthly live call-in trivia program that ran for about two years.

It was while I was at RISD that I discovered high-performance computer graphics workstations and was able to make the connection between computers and my interests in the fine arts. So, when I was given the opportunity, shortly after graduating, to take a full-time job at a computer graphics startup, I jumped at the chance.

One key role in that job over the next four years was to help artists familiar only with conventional tools make the transition to computer tools. I spent a lot of time, on the phone, at tradeshows, and in lectures/presentations, explaining complex topics in computer graphics to people whose most high-tech tool up to that point was often the waxer used for pasteups.

One tool I acquired during these years was the understanding that I needed to present my answers in ways that made sense to my audiences. I might have four or five different ways to describe the same concept or process, and I chose from among them depending on who I was talking to or training. (Because I was also a member of development teams, I took that learning back into the software design process as well as into my work specifying user experiences and interfaces.) Within a year of starting that job, I started writing monthly columns for industry trade journals and this is where I learned the importance of being clear, concise, and accurate. I had to say what I was asked to write about each month within a certain word limit – often as few as 300 or so words.

So, when I decided to make the leap from my (successful, high-paying) career in high-tech into chocolate, it was built on top of a foundation that had been many years in the making. While my epiphany was that, “while there were professional critics for just about everything you can think of, there were no professional critics for chocolate,” and I decided one afternoon to be the first, I also realized there needed to be a genre of literary criticism. Not just ratings, and not just reviews, but a larger literary context within which to place those reviews.

Graffito sprayed on the side of a dumpster. Humble source – great advice.

And that’s been my mission from the beginning of my ChocolateLife. I am sure there were formative experiences from your childhood and in the early phases of your career that similarly form the foundation of the Cacao Muse’s approach to writing about and educating people about, cocoa and chocolate.

With respect for our mutual love of language,

/Clay