Whither Geographic Indicators?

Would a Gruyère produced outside of Switzerland or France – here in the US? – taste just as sweet?

What happens when a judge misunderstands and confuses intellectual property (IP) protection regimes?

A US federal judge could have – mixmashing metaphors – pushed the first snowball down a slippery slope, leading to completely undermining the use and value of geographic indicators in the US. Not just in cheese but for any product currently protected by geographic indicators (GIs), protected designations of origin (PDOs), protected geographic indicators (PGIs), A(D)OC, and similar frameworks.

My (More Nuanced?) Take

Copyright laws protect the expression of ideas, not the ideas itself. There are some ideas, common tropes in literature and cinema for example, sometimes referred to as mise en scène, are not copyright protectable.

Trade and service marks protect the use of words, phrases, and images in commerce, and are designed to reduce consumer confusion in the marketplace.

Patents protect ideas that are (or can be) implemented in practical (as opposed to artistic, expressive) forms.

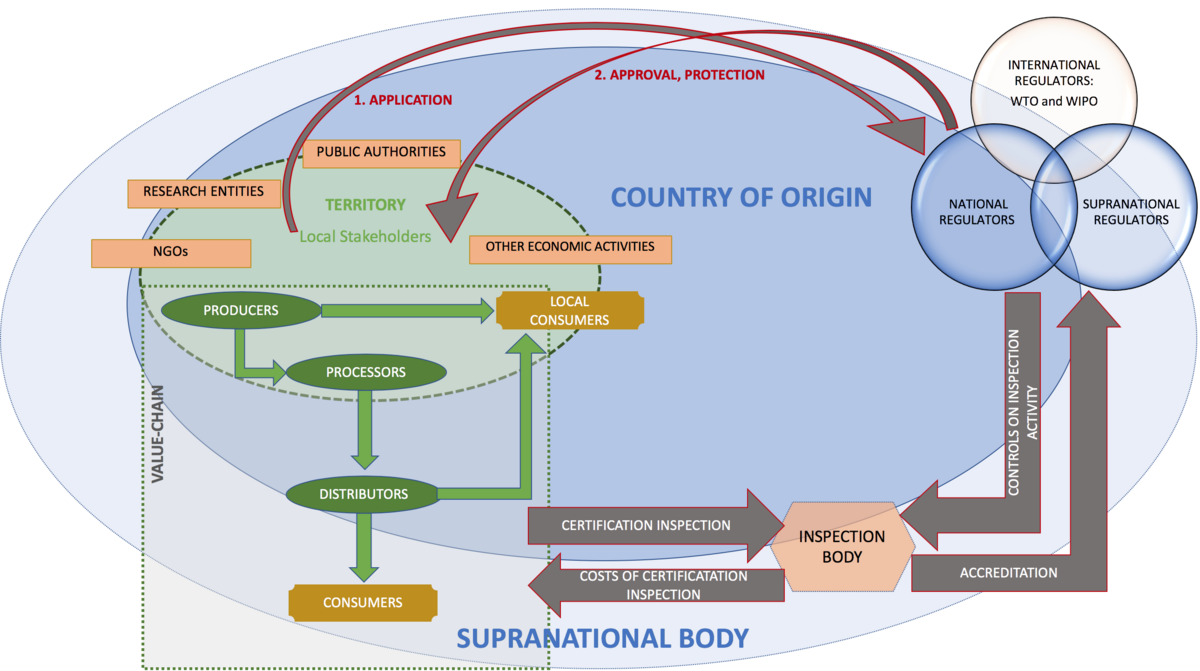

GI/PDO/A(D)OC designations incorporate elements of all of them – expression and nomenclature – uniquely tying the designation to a specific product and its location, methods of production and ingredients, and history.

Assuming the ruling is upheld on appeal, the judge, by saying that a cheese manufactured in the United States can legally be called Gruyère, despite being awarded protected status in the EU, makes it difficult if not impossible for the entities charged with regulating the use of the terms to ensure consumers they are buying authentic products.

Article 22.1 of the TRIPS Agreement (linked to under Resources) defines geographical indications as “...indications which identify a good as originating in the territory of a Member [of the World Trade Organization], or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.”

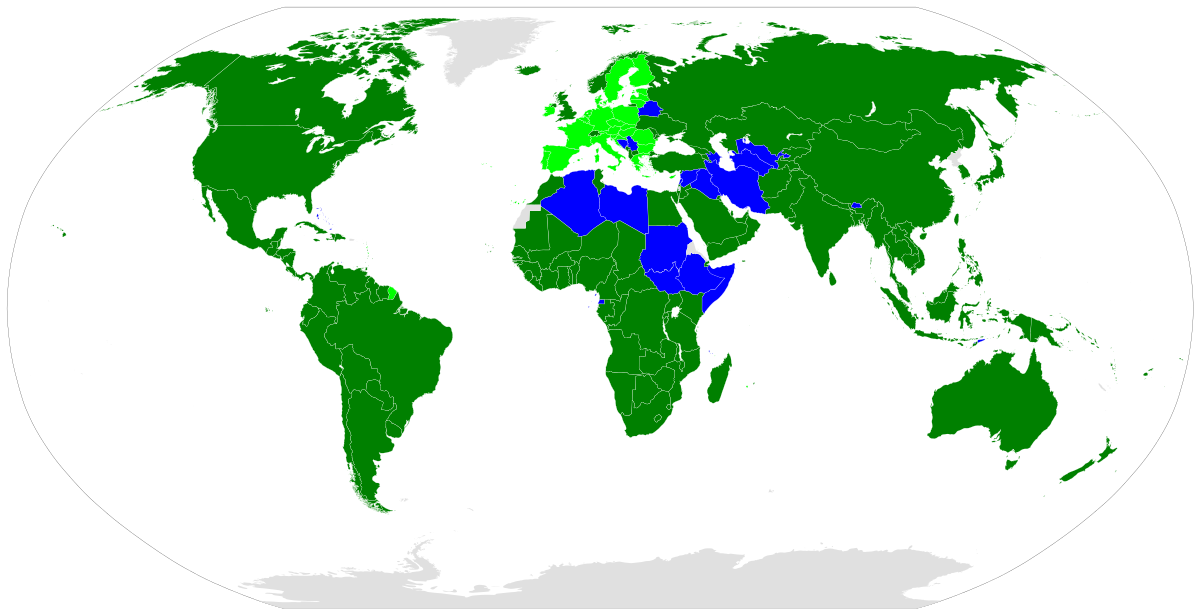

The United State is a signatory to the TRIPS Agreement.

The situation with Gruyère, as outlined in the Wikipedia article shows some of the nuance – there are differences between Gruyère made in Switzerland and France and there are rules about labeling that are designed to notify the consumer so they can make informed buying decisions.

The judge ruled that the term “gruyere” has become generic; that’s it’s like Kleenex® or Band-Aid® (brand adhesive bandages). And, that because the term has become generic, it cannot be protected under US trademark law.

The judge fails to comprehend, that a Geographic Indicator is not simply a trademark, it is much, much, more. IMO, this distinction is a distinction worth preserving.

GIs in Cocoa and Chocolate

The cocoa and chocolate industries are far behind other gourmet foods when it comes to place and process-based IP protection. There exists only a small handful of so-called DOs (denomination of origin/denominaciones de origen).

The OG DO in cocoa is Chuao. It has suffered from the beginning by being poorly written and the government of Venezuela has proven to be quite ineffectual (uninterested?) in protecting it against abuse.

There is a DO in Ecuador for Arriba (Nacional). It too is poorly written, and the rules and regulations governing its awarding and use are so onerous that there are very few who seek its protection.

This is a common challenge in the design of DO regulations. In Mexico there are more than 25 DOs and only two of them are in wide use, for tequila and mezcal. An analysis of the reasons why the rest are not widely used was a consideration in my work helping develop the rules for a DO for Cacao Grijalva in Tabasco and Chiapas from 2015-2019.

There is a balance that needs to be struck between what is being protected and how it is protected; too much bureaucracy and too high a cost create obstacles that few – especially poor farmers – want to even try to overcome.

The Belgian organization CHOPRABISCO has tried to create regulations around the use of the phrase “Belgian Chocolate.”

The main issues I see with CHOPRABISCO’s effort are:

- It lacks applicability/enforceability outside of Belgium

- Some of its definitions and regulations are non-sensical

A list of the companies who are signatories of the agreement shows some cracks in the protective armor – Barry Callebaut Belgium is a signatory, but not any BC company outside of Belgium; Godiva Belgium is a signatory, not Godiva Turkey or the US or elsewhere.

Confusing how? On the one hand, a chocolate (e.g., couverture) can be called truly Belgian if it is actually manufactured in Belgium. On the other hand, as I translate/interpret the regulations, a chocolate confection (praline) need only use Belgian chocolate in its shell to qualify to be called Belgian.

I know there is some confusion in the marketplace around what Belgian chocolate is and what being Belgian chocolate means because a lawsuit was filed against Godiva over this issue.

Conclusions and Actions

While we can all agree that the current copyright regulations really do suck in many ways and there are major flaws in the trademark and patent systems, there is no interest, from what I can tell, that those regulatory regimes need to be invalidated wholesale. There is widespread belief they need changing, but knocking them down to the ground is not among the changes being proposed.

This decision by the judge could affect how an entire class of intellectual property rights get protected, crippled, or killed. First it’s Gruyère – what’s next, Champagne? Maybe, under the same reasoning.

This may affect only consumers in the US. “Gruyere” made in the US probably can’t be exported to the EU and labeled Gruyère. “Champagne” made in the US probably can’t be exported to the EU and labeled Champagne.

It’s still yet another case of abuse of consumers’ wanting to trust in labelling. Now, when they go to the store and peruse all of the available options for Gruyère/gruyere they will need to pay closer attention to the label if they want to be sure they are getting the real deal.

Resources

Leave them in the comments below.