A Consuming Culture: Chocolate in New York City, 1750-1800

In the search for traces of chocolate in old New York, each discovery raises new questions about the merchants, makers, and consumers during the birth of chocolate culture in colonial North America.

Within the pages of The New York Weekly Journal dated January 10th, 1736, was a report of fire affecting “the Oil-Mill, Chocolate-Mill and Bolting-Mill…” operated by John Roosevelt on Maiden Lane in a part of the city known as Golden Hill near the bustling Fly Market. This marks one of the earliest references to offer a name and location in connection with chocolate manufacturing in 18th century New York.

Evidence suggests that by the 1750s chocolate had established itself, with at least a dozen makers in the city, but:

- Where was the raw cacao coming from?

- What methods were used to produce chocolate? and

- Who was consuming it?

A taste for drinking chocolate certainly followed European settlers into the American colonies, but it was the formation of the trans-Atlantic triangular trade routes (moving raw material, finished goods, and slaves) that brought an increasing amount of cacao into colonial port cities – primarily Boston, Philadelphia, Newport, and New York City (and to a lesser extent, southern ports from Virginia to South Carolina).

The earliest recorded arrival of cacao was aboard a Boston-bound ship in 1686. There remain, however, significant gaps in shipping records from this period, so one might assume that small amounts of cacao unofficially found their way into the colonies earlier. The Dutch, who established New Amsterdam in the 1620s, and the British, who took control of the newly christened New York in the 1660s, were both creating trade networks and colonial settlements in the West Indies which increases the possibility of early arrivals of cacao in New York. Of all ports, New York was also to some degree safe harbor for privateers (and pirates), whose stolen cargo may not have been recorded.

The slow, steady stream of cacao beans from the West Indies increased in the early 18th century, and as more of them passed through New York, more of them stayed.

New York’s early cacao trade was heavily influenced by a chain of events that began nearly two centuries prior, with the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion and subsequent migration of Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula into other parts of Europe, and eventually to North America. The migration of Jews and the spread of chocolate would sync up, most notably perhaps, in the Basque town of Bayonne in France, and later in the Caribbean under Dutch protection. By the 1650s the first Jewish immigrants began arriving in Dutch New Amsterdam, and with them, knowledge and experience that certainly forged a significant contribution to the city’s chocolate culture – trade, manufacture, and consumption – by the early 1700s. The ledgers of important merchants like Nathan Simson and Daniel Gomez reveal a steadily increasing flow of raw cacao coming in and out the port; among other points of origin, Jamaica and Curaçao dominate these records. By mid-century, there is also evidence of some finished chocolate being exported from New York.

As for makers, there are few clues leading to those who produced chocolate prior to Roosevelt, but surely finished product was circulating among this network of New York traders. Upon his death in 1708, the estate inventory of merchant Joseph Bueno de Mesquita appears to include ‘chocolate stones’ that found their way into the hands of Justus Bass and Giles Shelly – possible candidates as early makers whose trails otherwise go cold. Aaron Louzada is reported to have produced chocolate for Simson in the 1720s. William Dugdale, a businessman whose interests touched both milling and West Indian trade, is also thought to have sold finished chocolate in the 1720s, and enough of it to finance a home on Wall Street. Gomez advertised his own chocolate for retail sale near Burling Slip in the 1750s, and as we’ll read later, that extended family’s business would operate up to the end of the century.

Tight family and business connections emerge as a common thread among many of the chocolate-makers working in colonial New York.

Two generations of chocolate making begin with John (or Johannes) Roosevelt’s mills, the business handed down to sons Oliver and Cornelius. Also of note is that John is the progenitor of what we call the ‘Oyster Bay’ branch of the family, whose descendants include Theodore Roosevelt and his niece Eleanor. John’s nephew Isaac founded one of the city’s first important sugar refineries. The family’s reputation for wealth and power was established in this period and though his mills appear to have been his primary business, he dabbled in politics as a city alderman and had a taste for fine imported Dutch art and furniture.

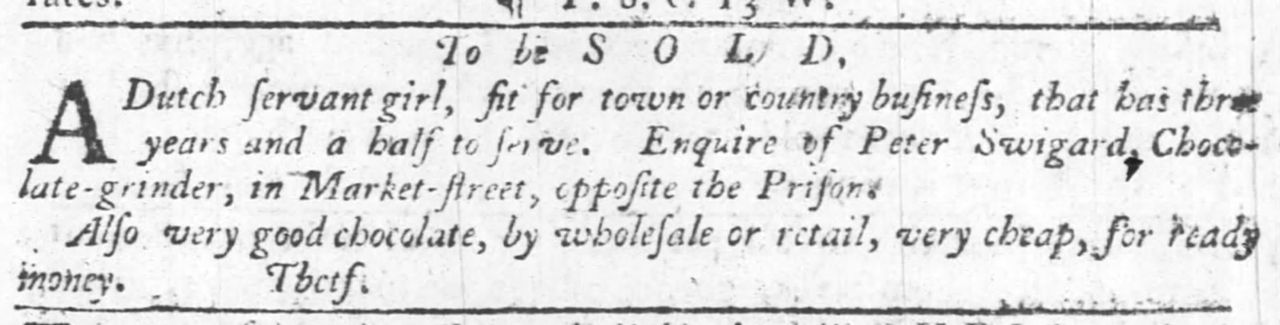

Another prominent maker active into the 1770s, was Peter Low, son of John Roosevelt’s sister, Rachel. His business was located at the corner of Maiden Lane and Broadway. The Pennsylvania Gazette notes in 1752 that Peter Swigard, a ‘chocolate-grinder’ supplying ‘very good chocolate by wholesale and retail’ on Market Street in Philadelphia; by the 1760s he was established in New York near Cow Hill (presumably so-named either for its proximity to the pastures of the Bowery, or for the slaughterhouses that lined the nearby Collect Pond). Peter’s son Jonathan, a loyalist to the British crown during the Revolution, appears to have fled the city after the war to continue chocolate-making in Canada. Dirck Schuyler, who in 1762 “continues to make and sell chocolate and candles, by wholesale and retail” also organized eleven other chocolate makers in the city in petitioning the New York General Assembly in 1775, “praying that the colony duty of four shillings per hundredweight, on all cocoa imported, may be taken off.” Ann Mary Schuyler, Dirck’s widow, bequeathed, “to Harmon Ling, the young man that now lives with me, my smallest chocolate mill and one hundred of the chocolate pans.”

Abraham Wagg, a wholesale grocer and chocolate maker, was the son of London-based Meir Wagg, a client of cacao trader Nathan Simson in the early 1700s. Abraham arrived in New York prior to the Revolution, and, as a loyalist like Jonathan Swigard, returned to England in 1779, but not before marrying Rachel Gomez. Rachel was the daughter of Mordecai Gomez, the brother of cacao merchant Daniel. Like his brother, Mordecai was involved in chocolate commerce; upon his death, the business continued in part through his son, Moses, but also by his widow, Rebecca. Though records reveal a few women selling prepared drinking chocolate, such as Susanna Dally, who was granted, “a license to sit in the said [Fly] Market and sell coffee, chocolate, cakes, and pies.” Rebecca Gomez stands out as the first woman known to operate as a manufacturer. Advertising from her “chocolate manufactory, no. 57 Nassau Street,” at the corner of Ann Street in the 1780s, she promoted a product that was “superfine, free from any sediments, and pure,” that was, “manufactured in the best manner.”

Sadly, we’ll never truly know what colonial chocolate looked like, how it tasted, and what “stylistic” differences may have existed from one maker to another, or from one city to another.

Solely by the numbers of known chocolate-makers offered by some researchers, it is suggested that Boston and Philadelphia may have produced more chocolate than New York during the colonial period. My own research, however, turns up several names that others seem to have overlooked. That said, while we assume chocolate was made in relatively small quantities for local communities, there was some inter-colony trade; in this early period, one was less likely to see the maker’s name and more likely to see chocolate identified by a sense of place, such as “Boston” or “Newport” chocolate.

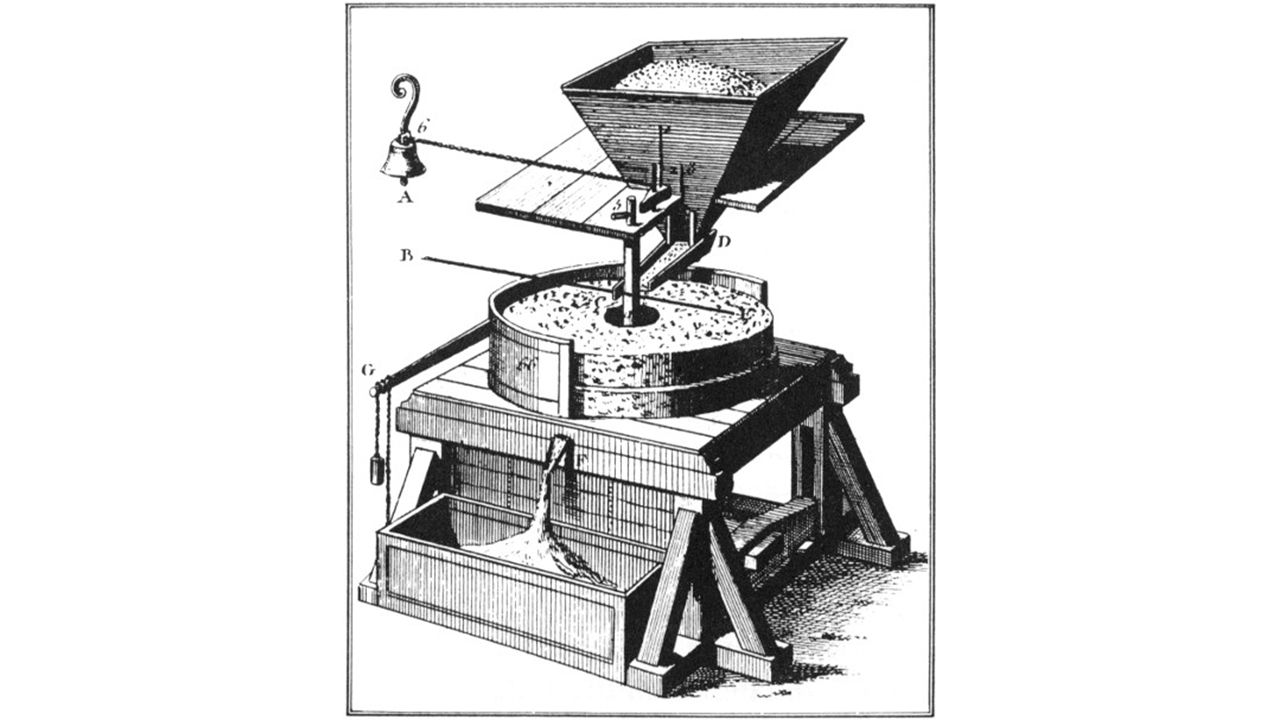

Methods used to roast, winnow, and grind cacao varied considerably. Milled in small quantities by hand, in larger mills under wind, water, or animal power, or by some combination of the two, it is well understood that many chocolate makers ground beans alongside other products using general-purpose mills that may have also processed spices, grains, mustard, or even pigments. Roughly hewn blocks or cakes of untempered chocolate likely whitened with bloom at the first hint of heat and humidity. Simply wrapped in paper or packed in crates, one might imagine that these unsweetened, coarsely textured chocolates also picked up any number of odors from their storage environment. Though spices and flavors were often added to the grated blocks at the preparation stage, some makers may have incorporated spices when grinding the cacao to produce something unique (or perhaps to mask off-flavors of sub-par beans).

We might have a tendency to shrug off colonial-era chocolate as ”primitive” or “bad” when judged by today’s standards and methods. I reject such a broad assumption and prefer to give our predecessors some benefit of the doubt as craftsmen who sought to create a quality product with the means at hand. Savvy consumers also developed preferences and a taste for quality.

The emergence of chocolate in North America coincided with the growing popularity of coffee and tea. In an era of poor sanitation, these “hot liquors” provided a hygienic alternative to drinking fresh water, joining alcoholic beverages like beer, fortified wines, and rum-based punches as preferred sources of hydration. Chocolate, coffee, and tea all offered stimulating effects, yet chocolate had a slight advantage due to associations with health and nourishment. Relative proximity to cacao-growing regions and the lack of import duties also worked in chocolate’s favor.

Taxes imposed on tea are what ultimately inspired the Boston Tea Party in 1773, and subsequent boycotts of British-trafficked tea may have spurred an increase in chocolate consumption on political grounds. Chocolate was enjoyed as a convivial social beverage, and by the end of the century from market stalls, but we might assume most of the chocolate consumed was with meals, or as a restorative, prepared in the homes of those who could afford it. Lighter infusions made with spent cacao shells were favored by some, George and Martha Washington among them.

Just as many of the makers and merchants involved in chocolate commerce were well-to-do, one might also assume that chocolate was consumed primarily among the wealthy households of New York City. The wills of the gentry often listed among other items of value, chocolate pots and serving pieces, as well as significant quantities of chocolate itself. Established makers were supplying to wholesale trade and retail, but the wealthiest New Yorkers with a staff of servants may very well have been roasting, shelling, and grinding small quantities by hand in the home.

Though New York from its earliest days enjoyed a distinctly cosmopolitan air and independent (if not progressive) spirit, its role in the slave trade is often overlooked. A surprising amount of forced labor in the city persisted and peaked in the middle of the 18th century. Slaves and indentured servants were imported in the early days of the Dutch colony. The slave market (colloquially known as the “Meal Market”) constructed at the foot of Wall Street at the East River operated from 1711 to 1762; in that period up to 20% of the city’s population was comprised of enslaved men, women, and children. Incremental legislation toward the abolition of slavery began in the post-war years of the 1790s, but full emancipation in the state of New York was not fully realized until 1841.

From the households of wealthy cacao merchants to the mills and workshops of chocolate makers, slave labor is intrinsically tied to the culture of chocolate in the American colonies.

Though forced labor and the slave trade were foundational to the economies of northern cities and farms from Massachusetts down to Pennsylvania, New York bore the distinction of having the second-largest slave population of all thirteen colonies. Recent and forthcoming work from historian Christopher Magra explores slave-made chocolate in Newport, Rhode Island, and research has unearthed notices in New York and Philadelphia newspapers either advertising the sale of slaves or offering rewards for escaped slaves.

Among them, the notice posted by Peter Swigard in 1752 before arriving in New York; in addition to promoting his wares, he announces:

Peter Low on Maiden Lane in 1771 describes the appearance and mannerisms of “Symon”, a runaway slave, offering “two dollars, and if taken out of the City of New York, four dollars reward.” Low’s uncle, John Roosevelt, was a slave owner as well; though Roosevelt did testify to his innocence, a young man under his ownership named Quack was found guilty and executed for his role in conspiring in an alleged “slave rebellion” in 1741.

Most of the written histories of chocolate focus on the 1765 founding of a chocolate mill in Dorchester, Massachusetts ...

... claiming it to be the first chocolate factory in North America. The company begun by John Hannon and later rebranded by James Baker and grandson Walter would indeed evolve into an iconic brand that would dominate the chocolate and cocoa market in the 19th century. It’s a convenient hook on which to hang the story of chocolate and thus the tale has persisted, thanks to the power of marketing and brand recognition. It obviously overlooks decades and the dozens of makers at work grinding chocolate throughout the colonies. We might, however, rightly give the Walter Baker Company some credit for the company’s ability to produce on a scale to reach a wider customer base; the growth of regional brands serving Boston, New York, and Philadelphia and the competition between them would drive the chocolate market as methods improved and trade expanded in the 1800s.

Other chocolate makers discovered during the colonial period of 18th century New York include John Austin, Daniel Hogan, Joseph Leary, Joshua Levy, Peter and Benjamin Montayne, James Wilkes, and David Whitehill. Others emerged after the Revolutionary War, which marked a cultural and economic reset of sorts for the city. Francis and John Van Dyk, Tobias Van Zandt, and Jedediah Waterman were among the makers who, by 1800, were specializing in chocolate-making, a subtle but significant shift from multi-purpose mills. The post-war boom also provided a growth spurt for the city; its population doubled from 1775 to 1800. The trends toward urbanism, industrialization, and capitalism would all help propel chocolate culture in the years to come. Chocolate entered the 18th century and the port of New York as an exotic elixir shipped in from faraway lands and consumed in large part by the wealthy.

Chocolate welcomed the dawn of the next century, much like the fledgling country of the United States, democratized to some degree. It was enjoyed less as a rarified luxury and more as a part of daily life.

I look forward to an opportunity to discuss this period of chocolate history in New York City in greater detail on Thursday, June 24th in The Chocolate Life room on Clubhouse. Clay and I will open up the conversation to explore both the particulars of the colonial chocolate experience and the larger issues that emerge from the research. Follow along on this six-part series by reading an introduction about my motivation and methods used in researching these little-known stories.

Featured Image Credit: Fly Market, William P. Chappel, 1870s, Oil on Slate Paper, Public Domain, Retrieved from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.