A Second Revolution: Chocolate in New York City, 1800-1850

After the country gained independence, New York City grew its cultural and economic influence (and size) with the emergence of the Industrial Revolution. The same winds of change would propel the nature of chocolate into the 19th century with new methods and applications.

The opinionated French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin is probably best known for his aphorism, “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are.”

It’s not surprising that he also had a few things to say about chocolate.

In The Physiology of Taste published just months before his death in 1825, Brillat-Savarin extolled the virtues of chocolate as a digestive aid and muses on the addition of sugar as a condition of the bean’s inherent aroma and degree of roast. He also references the evolution of chocolate making machinery.

“For a long time machines have been employed for the manufacture of chocolate. We think this does not add at all to its perfection,” he declared, “but it diminishes manipulation very materially, so that those who have adopted it should be able to sell chocolate at a very low rate.” The first English edition, translated by Fayette Robinson in 1849, includes as a footnote to Brillat-Savarin’s sentiment, “One of those machines is now in operation in a window in Broadway, New York. It is a model of mechanical appropriateness.”

In Catherine Havens’ Diary of a Little Girl in Old New York, we catch a glimpse of mid-century Manhattan as seen through her ten-year old eyes. She grew up in a wealthy family and lived on East 9th Street near present-day Astor Place. In an entry dated December 10th, 1849, Havens writes, “On the corner of Broadway and Ninth Street is a chocolate store kept by Felix Effray, and I love to stand at the window and watch the wheel go round. It has three white stone rollers and they grind the chocolate into paste all day long.”*

The Doggett’s New York City Directory for 1849 lists Felix Effray as a “French confectioner and sweet chocolate maker” whose residence and business address was 457 Broadway, between Howard and Grand Streets. At the time, he was 41 years old, a widower, and the father of four children. A native of Paris, we first notice Effray on Fulton Street in Brooklyn making “sweet chocolate for family use” in 1838; he opened his Broadway factory store in 1841. A prominent advertisement in The New York Herald on September 26th, 1842, lists among his chocolate offerings, “very fine” sweet chocolate, cocoa paste, ground cocoa in bags, and chocolates flavored with vanilla, cinnamon, and pistachio. Also included is a sweet chocolate “of Good Health,” and molded “figures” of fruits and animals. His “confectioner’s hall” of retail and wholesale goods must have appeared a colorful, sweet-smelling oasis in the busy shopping district – stocked with goods from whole vanilla beans and marshmallows to gum paste ornaments and fancy imported papers and boxes.

In Effray’s shop we see the evolution of chocolate slowly shift over the fifty years from its humble colonial roots. The means of production had moved from primitive chocolate-works in dock-side warehouses and into tony commercial districts, the process and machines now prominently displayed in shop windows under the mark of the maker’s name.

Though chocolate would remain a staple beverage through the end of the century, its full potential in an array of confectionery and pastry applications was just being discovered.

NOTE: While Effray did move his shop to 771 Broadway at the corner of 9th Street around 1860, he had operated at Broadway and Grand Street a dozen blocks to the south for almost twenty years. That Havens mixed up the date and the location is, perhaps, an honest mistake, and suggests the entry was not written contemporaneously, but filled in by memory well after the fact.

The City

It’s difficult now to imagine the concrete jungle of Manhattan in its once natural state. New Amsterdam was established at the island’s southern tip, and for much of the Dutch period in the 17th century, was confined to the streets and canals below Wall Street. At the turn of the 19th century, the grid of numbered streets and avenues that would fill in the length of Manhattan had yet to be conceived. Consider, if you will, a time when the city was largely contained below present-day Canal Street, beyond which lay meadows and marches, hills and streams, the landscape punctuated with farms and sparsely populated settlements. That would soon change. The rise of manufacturing and technology, the primacy of its port, and its position as a gateway for multiple waves of immigration all contributed to the city’s rapid growth The city’s population doubled from 1775 to 1800, doubled again by 1820, and again by 1840. As New York City spread out, so too did the city’s chocolate makers.

City directories and other records show that prior to 1800, most of New York’s known chocolate makers operated in close proximity to the slips along the East River. The factories were built along Water Street and Queen Street (present-day Pearl Street), situated a few blocks inland on Beekman Street and Maiden Lane toward Broadway, and on Broad Street, today the beating heart of the city’s financial district. Following the city's spread, chocolate makers would fan out along the thoroughfares - up the Bowery into what today is the Lower East Side, along Cherry Street into the Two Bridges neighborhood, and up Broadway into the future-fashionable districts of TriBeCa and SoHo.

Meeting and exceeding the local demand for chocolate, New York City’s manufacturers would also expand their reach into a growing country.

Cacao

Browsing the digitized pages of The Evening Post starting from 1801, I find in each day’s edition news of the brisk shipping business at the port of New York. Ships’ captains solicited passengers and cargo for their pending departure, and arriving vessels announce the bounty of goods to be unloaded. Many of the brigs and schooners making the three- to four-week journey up from the West Indies held cacao within their hulls. The merchants buying and selling the beans noted their port of origin: Caracas, Santo Domingo, Cap François, Grenada, St. Lucia, Cayenne. Cacao from Trinidad was less common, as the British for a time only allowed exports from the island in their own ‘bottoms.’ And though they may seem small compared to today’s volumes, the quantities of cacao beans in the merchant stores were not insignificant. On any given day their inventory might range from half a ton to five tons, put up in bags, boxes, and barrels (logged in archaic units of tierces and hogsheads). Sold by the hundredweight (cwt), prices fluctuated; Caracas beans originating from coastal Venezuela consistently fetched prices at least 25% higher than ‘common’ or ‘island’ beans from elsewhere in the Caribbean. By mid-century, increasing volumes of cacao from Maracaibo (Venezuela), Guayaquil (Ecuador) and Para (Brazil) are also entering the port of New York.

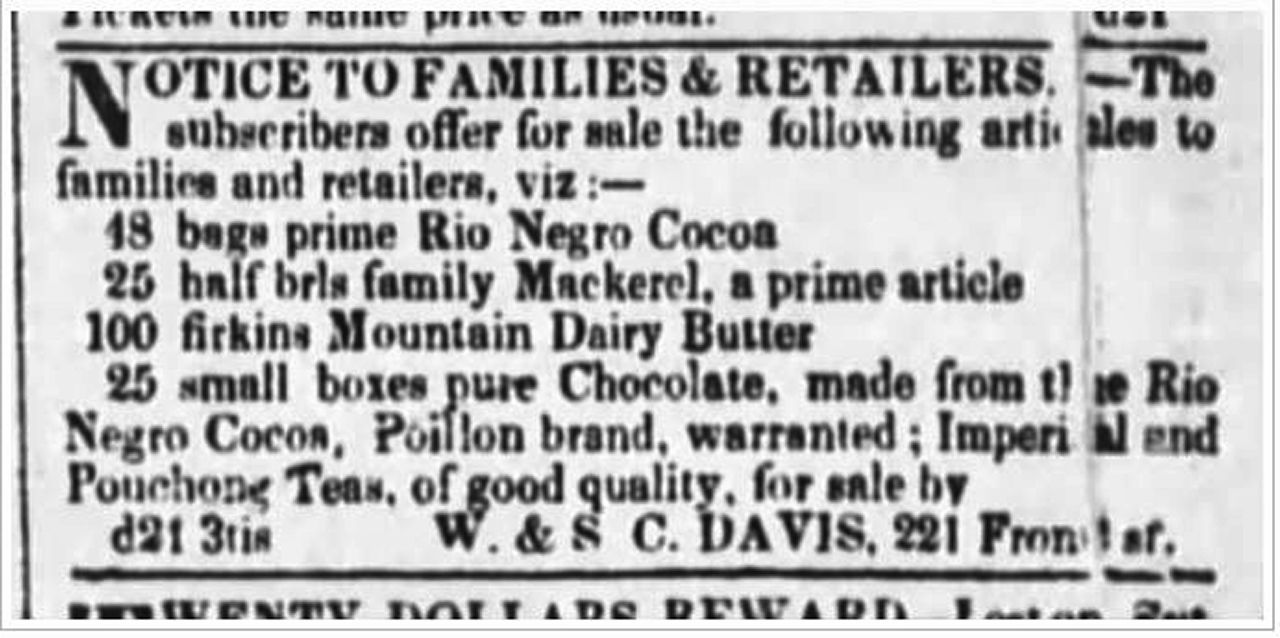

An 1830 newspaper advertisement posted by a New York merchant marks one of the earliest attributions of origin to finished chocolate, “pure chocolate, made from the Rio Negro Cocoa, Poillon brand, warranted,” referring to the Amazon basin tributary that flows from Colombia along its border with Venezuela and into the Amazonas state of Brazil.

In addition to raw material, the wholesale dealers were also selling finished chocolate made elsewhere in the Northeast. Despite any differences in chocolate that might be attributed to the methods and means of the maker, the city of manufacture, or the quality of raw material, the product of the 1700s was often marketed generically. One begins to see chocolate advertised simply as ‘Boston’ or ‘Philadelphia,’ occasionally with quality grades ‘No. 1’ or ‘No. 2,’ though it’s unclear what might have distinguished one from the other. In this period we also see the manufacturer’s name appear on chocolate products with more frequency. In 1802, a listing offers for sale “first and second qualities warranted chocolate” from well-known Albany maker James Caldwell.

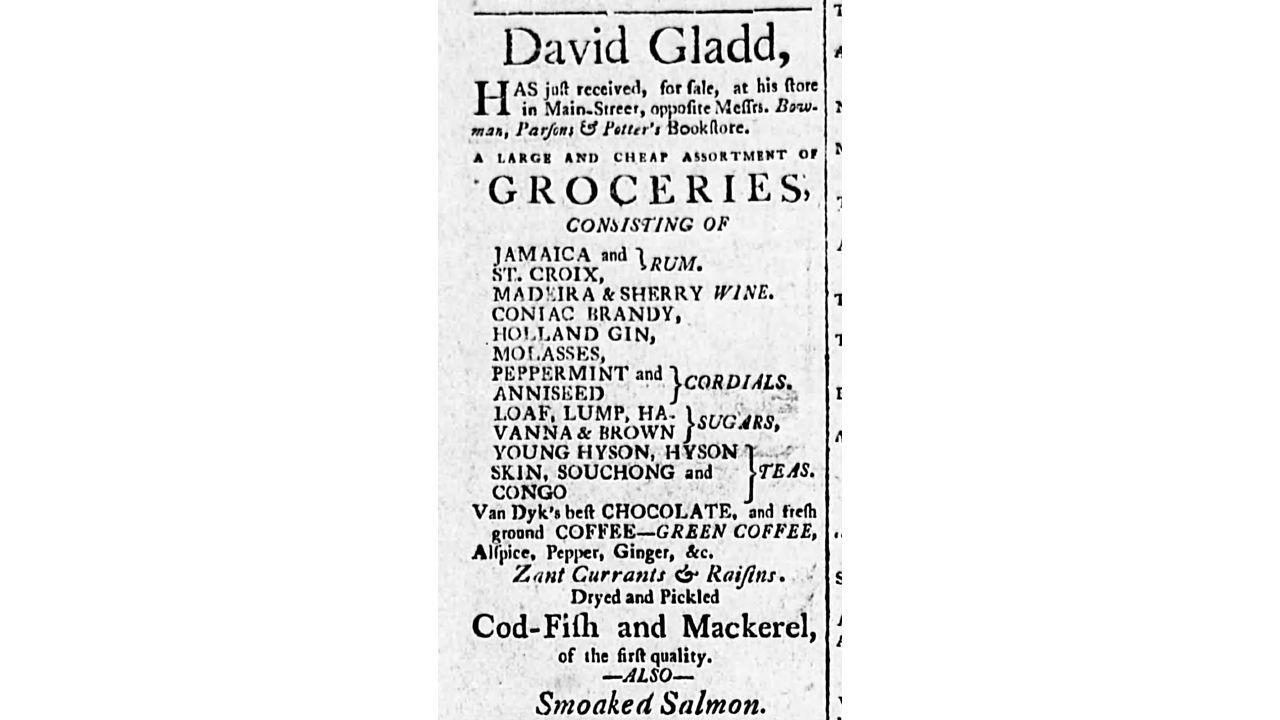

A year later, Saltus, Son & Co. posted notice of New York maker Francis Van Dyk’s chocolate for sale. While many makers began to specialize in chocolate manufacturing in the post-colonial period, there remained wholesale grocers and merchants who processed their own cacao alongside other goods (mustard, in particular, was commonly milled alongside chocolate). One of the earliest notices of machinery for sale was in 1806 for, “a set of works for manufacturing chocolate, complete, for sale, either to be removed, or can be employed as they now stand in a fireproof store,” at 297 Water Street, a warehouse formerly occupied by merchant Robert Thurston.

There is little evidence of imported chocolates from abroad being sold in New York in the earliest years of the 1800s. When it does arrive, it will infuse a noticeable French accent to the language of American chocolate.

Makers

While the names of many of the grinders working in the 18th century remain lost to history, at the turn of the 19th century we see more of them emerge from the shadows of anonymity. In part due to specialization of the craft, and perhaps in part due to the increased volumes they may have produced. The visibility to researchers is also the result of preserved records. The newly formed United States tallied its first census in 1790. Bear in mind, however, that for sixty years these records would primarily list male heads of households, their dependents represented by check marks under inquires based on gender, age, and race. As those census records become more nuanced throughout the 1800s, we can tease out the identities and activities of these makers: their age, where they lived, their immigration history, and family connections. Most useful in charting the spread of chocolate are the annual New York City directories, the first of which was published in 1786.

These early records list the city’s occupants by name, occupation, and address (in years that followed, making the distinction between business and residential). By laying these records out over a broad timeline we see individual chocolate makers moving their factories around, from older parts of the city uptown into newly developing neighborhoods. We see cross-pollination of partnerships forming, dissolving, and reforming among makers, which suggests chocolate-making was a competitive business that also fostered a sense of community. We see among the wax and wane of individual businesses that a few addresses remain constant as sites of chocolate-related activity, which helps us understand some of the early transfers, mergers, and acquisitions that may have taken place.

By 1800, many of the names associated with chocolate in the late colonial period fade away and new makers emerge. Active in the 1790s, John Austin and Tobias Van Zandt were among the first makers that comprised a cluster of chocolate factories along Water Street. Previously operating on Broad Street, Joshua Levy appears at 2 Water Street in 1800. Jedediah Waterman married Van Zandt’s daughter Johanna and began making chocolate in the 1790s; he later moved his business up to 322 Water Street and remained in operation into the 1820s. John Poillon’s grocery business, found at 59 Whitehall Street in 1801 (today near the Staten Island Ferry Terminal) would shift its focus to chocolate and cocoa. By 1805 his first factory appeared on the Bowery, and continuing on with his son Peter, the Poillon chocolate works moved as far up as Houston Street, in the heart of what would become the Lower East Side until 1860.

A retail business begun by the Crommelin family near the “Meal Market” in the 1740s would launch another ‘dynasty’ in chocolate that spanned a century. Subsequent generations had steered the family business further into the wholesale grocery trade, and in the 1810s Robert Crommelin was processing chocolate at 227 William Street, alongside the production of mustard, coffee, rose water, and other goods. After Robert’s death in 1815, his nephew Charles Crommelin Cogswell continues making chocolate on William Street for another decade; his son Jonathan Cogswell appears to have continued grinding uptown on Spring Street into the 1830s. In this same period, Robert Crommelin’s sons Frederick and Joseph set up chocolate factories in Brooklyn which would move around the borough and operate into the 1860s. A separate branch of Crommelin cousins, George and Armand, appear in Philadelphia maintaining a chocolate making business there in the 1830s and 1840s.

Another tangled web of familial chocolate making is found in the Van Dyk story. Beginning with a mill run by his father Nicholas in Newark, New Jersey in the 1760s, John van Dyk (active in many of the Revolutionary War battles in the greater New York area) and his brother (or cousin) Francis continued the trade in Manhattan in the 1790s. John’s business operated on Broad Street until he settled in Brooklyn in the early 1800s. Francis made chocolate at Beekman and Nassau Streets. By 1808 the factory Francis built was run by Noel Blanche for several more years, in partnership with Peter Malard and then John Black. Blanche and Malard appear separately in different locations in the subsequent years, while a John Black (perhaps a son) is listed as a confectioner on the Bowery at Delancey into the 1850s. John Van Dyk’s daughter Sarah married Joseph Meeks.

Meeks is best known as a furniture maker, his pieces on view in museums and sought after by collectors. His Broad Street workshop, where he is listed as a “cabinet maker” in 1804 is shown for a brief period to be making chocolate around 1815. Meeks’ would return to woodworking and enjoy his most productive and profitable period in the decades to follow. The Van Dyk chocolate business would later shift to coffee and remain a regional importer and roaster into the 20th century.

As chocolate-making ventures specialized and moved into new (and one presumes larger) digs throughout the city, it’s unclear how much production was influenced by ongoing advances in manufacturing technology up to the 1830s.

Mechanization

The mechanization of chocolate appears to follow the path of the greater Industrial Revolution, originating in 18th century Great Britain and proliferating into continental Europe and later over to North America. Textile mills were among the first industries to mechanize, and improved grinding methods followed. Adapting the technology they saw evolving around them, it seems inventive chocolate makers themselves drove most of the early innovation. Walter Churchman may have been the first to operate a chocolate mill with a “water engine” he developed in Bristol, England in the mid-18th century. Already making chocolate for a decade, Joseph Fry purchased Churchman’s business (and intellectual property) in the 1760s and in the 1790s installed a steam engine after the well-known improvements made by James Watts. Specific references to steam-powered chocolate works in New York City appear with regularity in the mid-19th century; among the first to prominently boast of his steam manufacturing was Henry Maillard in 1850 after the launch of his first factory at 401 Broadway.

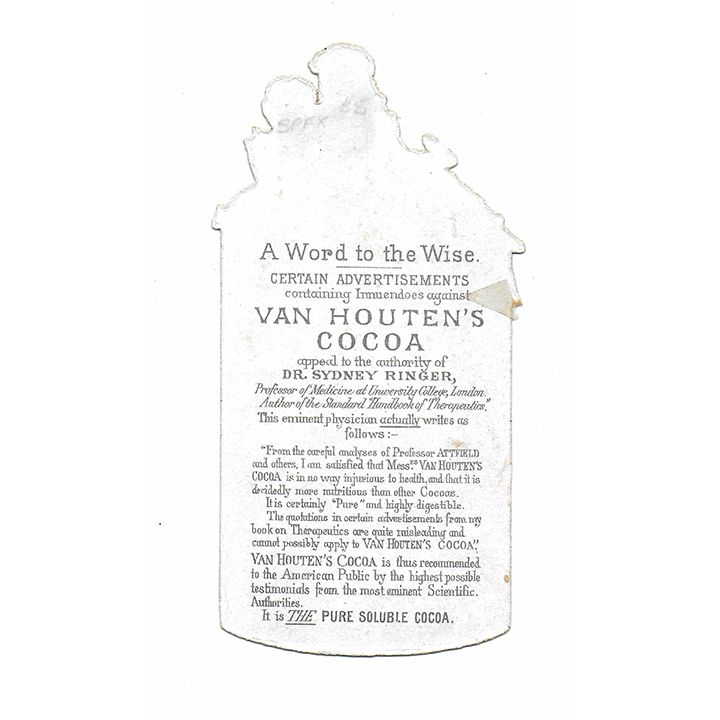

What began as a mill run on manual labor, the Amsterdam chocolate business of Casparus Van Houten would evolve into one of the world’s most recognizable cocoa brands. His 1828 patent for an efficient hydraulic cocoa butter press marks for many an important inflection point in the evolution of chocolate. The desire for lighter, less-fatty drinking chocolate led to various attempts at removing the bean’s cocoa butter prior to Van Houten’s invention. Various kinds of manual presses were employed, as well as the “broma” process, which involved hanging bags of ground liquor in warm rooms, the slow drip of fat leaving behind a partially defatted product that would remain popular throughout the 19th century. Van Houten’s press, and his son Coenraad’s process for alkalization paved the way for cocoa powder – almost instantly dubbed as “digestible” or “soluble” – for use as a beverage and, later, in confectionery and pastry applications. The Van Houtens’ technology became more accessible when the original patent expired in 1838. It is unclear exactly when machines based on Casparus’ original design were in use in New York City, but references to prepared cocoa powder emerge early in the 1840s. Coenraad’s son, Casparus Johannes (C.J.) joined the company in the 1860s and helped propel the brand on an international scale. By the 1890s, C.J. Van Houten and Zoon maintained a branch office in New York City at 106-108 Reade Street.

L-R: Van Houten's Cocoa, Die-Cut Advertising Trade Card, 1890s (recto); Van Houten's Cocoa, Die-Cut Advertising Trade Card, 1890s (verso); Business Card, C.J. Van Houten & Zoon, 106-108 Reade Street, New York City, 1890s. All images Collection of the Author

The hydraulic press created more versatility and opportunity for the solids of the bean but use of the cocoa butter byproduct was slow to catch on. Though cocoa butter is today considered the most valuable fraction of the bean, its early use was mostly confined to pharmaceuticals, which took advantage of the fat’s unique melting properties.

Largely confined to the cup and consumed with a ritualized regularity akin to coffee and tea in the first half of the 19th century, the origins and frequency chocolate being used in other applications is not well-studied. Experimentation with chocolate’s versatility as an ingredient likely began in Europe; the first products resembling bonbons and chocolate-flavored candies in New York appear in the stores of grocers specializing in imported French goods. Delicate sticks or ballotins of chocolate began to appear alongside the large cakes meant for grating into beverages. Virtually unknown in colonial America, vanilla began to find its way into chocolate alongside conventional spices.

Descriptions of early attempts at producing solid or “dry” eating chocolates suggest they provided an instant dose of energy, but perhaps not much gustatory delight. With the addition of sugar and improved milling methods, we might more generously compare the “sweet” chocolates produced by mid-century to the “two-ingredient” style of chocolate popularized by today’s craft movement.

It is generally accepted that the Joseph Fry Company in England “invented” the modern chocolate bar with the supplemental addition of cocoa butter to liquor and sugar in 1847. A higher fat content improved the eating experience and made possible delicate dipped confections that require a fluid consistency. After steam-powered mechanization, and the efficient fractioning of cocoa solids and fat, Fry’s innovation is often seen as another great leap in chocolate’s evolution. Seeing this achievement in the context of what other chocolate makers were doing in this period might force a shift in perspective.

Rather than a leap forward from a standing start, Fry’s pivotal moment is an important passing of the baton, an opportunity to accelerate on the momentum provided by previous chocolate makers.

Chocolate Ex-Machina

But what of Felix Effray’s stone wheels, that so captivated a young Catherine Havens and represented the latest in technology in the eyes of Fayette Robinson? Was this machine the type of stone melangeur that, in part, later inspired the modern craft chocolate movement?

The machinery used by early 19th century chocolate factories may have been based on generalized milling technology, perhaps modified for the particular needs of chocolate. References to New York millwrights who produced equipment tailored specifically to chocolate only begin to appear in the 1860s (we also begin to see a common cross-over between chocolate and coffee processing). The invention of the heavy melangeur-style mill consisting of stone wheels that rotate with the action of a spinning stone base – and the basic design of inexpensive tabletop wet grinders used widely today – is attributed to Swiss chocolate maker Phillippe Suchard in the 1820s. As trained chocolate makers and confectioners from Europe arrived in New York City beginning in the 1840s, it is plausible that they brought with them not only skills adapted to emerging chocolate confections but also the tools and technology that hastened their popularity. Indeed, an 1844 advertisement taken out by Effray in the New York Daily Herald describes his “French-style sweet chocolate, made with a French machine.” In an earlier ad, Effray “takes this opportunity to inform the public that he has at work a machine in his store to show how nicely the article is made.”

Effray was one of the first immigrant chocolate-makers to arrive in New York City. Behind him was fellow Frenchman Eugene Mendes from Lyon, who we initially find on William Street in 1844 and later that decade, on Fulton Street between Broadway and Church Street. By the early 1850s Louis Thourot, Evariste Martin, and Louis Battais have also arrived from France, as well as Joseph Govaerts and Nazaire Struelen from Belgium, and Albrecht Klix from Germany. With their arrival, confectionery becomes more closely tied to chocolate-making; the city directories and census records list their occupations as chocolate makers or confectioners, or both. As a researcher primarily looking to narrow my focus on those who worked directly from cacao beans, this period begins to present challenges.

Many of these early confectioners (and large candy manufacturers that emerge later in the 19th century) made their own base chocolate, but as time goes on the distinction between makers and fondeurs becomes blurry.

It’s interesting to note the age of these immigrant chocolate-makers, many of whom were in their late twenties and early thirties – old enough to have developed skills as craftsmen, but young enough to uproot themselves in search of opportunity. Whereas the wave of Irish arrivals in the 1840s were compelled to leave out of necessity, fleeing years of famine, one might imagine these continental arrivals had entrepreneurial motives. We can only speculate what potential they saw for themselves in the fast-growing city. The convergence of technology and confectionery applications with the arrival of these Europeans certainly changed the course of chocolate culture in the city. Arriving in New York City in 1848, it would be Henri Maillard, among this group and others that followed, who perhaps left the most lasting impression in the decades to come.

The Birth of Brands

Some of New York’s chocolate makers in this period began to enjoy some degree of brand recognition beyond the immediate region. Poillon cocoa and chocolates were available from Burlington, Vermont and Hartford, Connecticut down to Nashville, Tennessee and Charleston, South Carolina. Eugene Mendes’ “French chocolates” appear in Charleston and Wilmington, North Carolina. Effray’s was sold in Newport, Rhode Island and Thourot’s chocolate made it as far as Kansas.

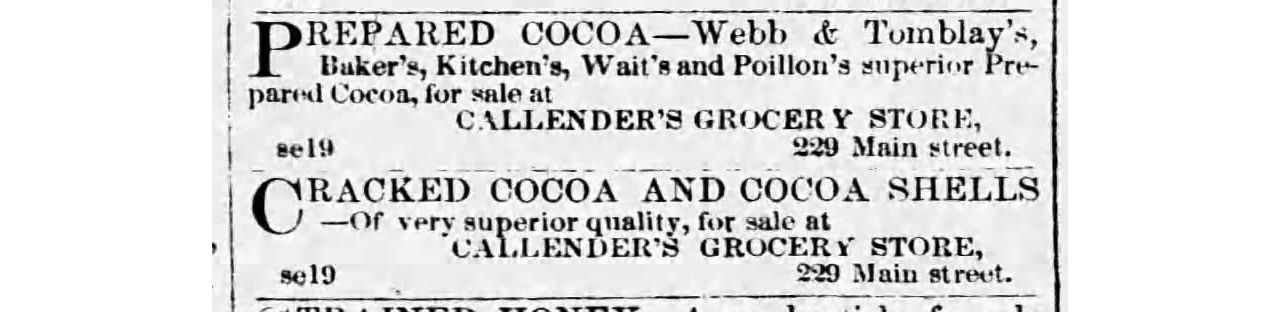

The potential reach of these brands increased with the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 (and the introduction of steamboats), decades before the boom of overland railroad construction. Situated at the mouth of the Hudson River, the city’s port served as the Atlantic coast gateway to the canal. Inland water access to developing markets connected to the Midwest through the Great Lakes, and to the South via the Mississippi River system to the Gulf of Mexico. A grocer’s advertisement in The Buffalo Commercial in 1850 lists for sale multiple brands of prepared cocoa; alongside Boston brands Walter Baker and Webb & Twombley are products from New York makers Poillon, George Kitchens, and John Wait.

On a national level, the Baker Company was just beginning to solidify its dominance in the market. As for imported chocolates, Masson of Paris is among the first to arrive from France, and British firms such as Taylor and Fry only appear sporadically in newspaper advertisements prior to the mid-1800s.

Diversification

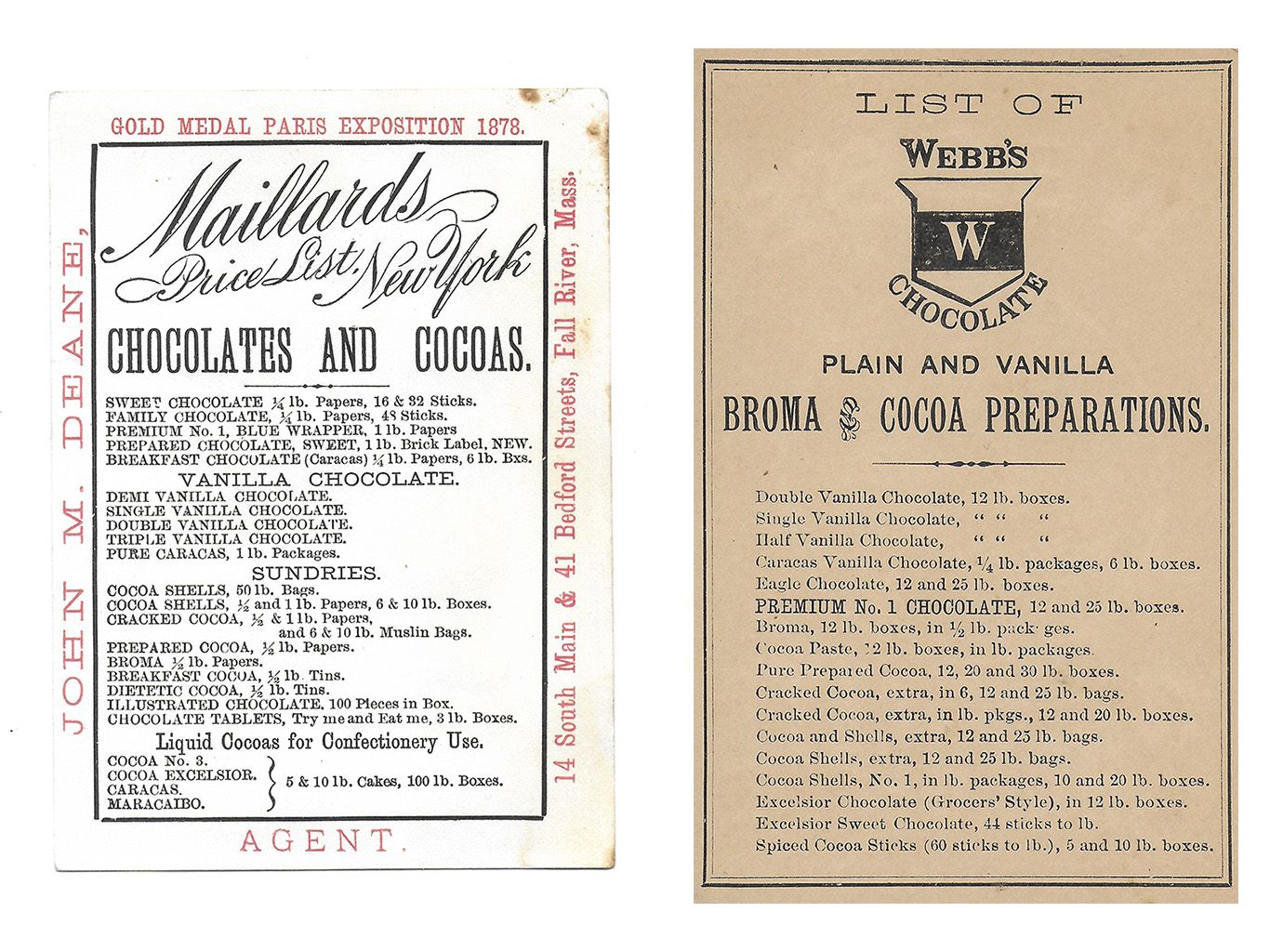

Just as chocolate began finding its way into more varied applications and confections, the products available to consumers also diversified. Makers offered solid chocolate in shapes and sizes beyond simple cakes, formulated for drinking or for eating, and in some cases, highlighting the qualities of a single origin bean or thoughtful blending of multiple types of beans. Vanilla became increasingly popular and makers began dosing it in varying amounts. Proprietary names given to new products became synonymous with their makers. Cocoa powders appeared under a variety of formulations, sometimes with added sugar or starches. Richer broma was also common. Makers sold nibs, or “cracked cocoa,” and shells. Some were preparing liquor and chocolates in bulk for sale to other confectioners.

The advertising cards below – one from New York City’s Maillard, the other from Boston’s Josiah Webb – though both dating to 1870s and 1880s, show this range of products that were appearing in grocery stores by the 1850s.

Cookery Books

Though we see the worlds of the chocolate maker and confectioner intersect in this period, it is difficult to say for sure how prevalent the use of chocolate and cocoa powder as a base in cakes, pastries and ice creams was, at least among North American cooks. Newspapers of the day can tell us what ingredients were for sale by grocers, but they had little in the way of recipe or lifestyle content as we think of it today. Attempting to chart this transition from beverage to culinary uses, I undertook a brief (if not incomplete) survey of a few prominent cookbooks published throughout the early 19th century. I discover a range of responses to the use of chocolate in recipes. Three factors seem to influence the appearance of chocolate-flavored applications in the mainstream: the date of publication, whether the author was writing from a European or an American perspective, and whether the intended readers were the home cook or professionals.

- The Art of Confectionary [sic], Edward Lambert, 1761. This professional-leaning text from the 18th century published in London concerns itself primarily with fruits, nuts, and sugar work, but no chocolate.

- The Complete Confectioner: Or The Whole Art of Confectionary Made Plain and Easy, Hannah Glasse, 1765. Published in London, Glasse offers an interesting beverage combining chocolate with cream, white wine, lemon, sugar, and rosemary. Two more recipes, "chocolate almonds" flavored with orange flower water, and an egg white-lightened "chocolate puff" suggest some of the earliest confections.

- The Practical Confectioner, James Cox, 1822. Largely intended for the home cook, published in London, it includes just two recipes incorporating chocolate – ice cream and chocolate drop candies.

- American Domestic Cookery, Maria Rundell, 1823. Offers two recipes for drinking chocolate.

- Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats, Eliza Leslie, 1832. With several editions printed after it first appeared in 1828, this book was popular among home cooks. The 1832 edition, however, contains no reference to chocolate.

- The Cook's Own Book: Being A Complete Culinary Encyclopedia, “a Boston Housekeeper,” (Mrs. N.M.K. Lee), 1832. Perhaps the first alphabetically organized cookbook published in America, It is fairly thorough in presenting roughly a dozen recipes for chocolate confections, conserves, ice creams (and a type of sorbet), chocolate-infused brandy, and petit pains.

- Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien, Marie Antonin Câreme, 1834. Câreme is, among other things, credited with codifying many of the standards of modern French haute pâtisserie. This complete collection book was published a year after his death in 1833, which places this work amid the period of experimentation with chocolate in pastry applications. Reading the many recipes that incorporate chocolate, one gets a sense that Câreme is not only exploring its flavor potential, but also understanding chocolate on a functional level. Chocolate appears in soufflé, bavaroise, numerous creams, cakes, pastry fillings, glazes, fritters, profiteroles, blanc manger, and as minor decorative elements in his well-known pièces montées. In addition to chocolate, we find Câreme working with nibs and whole cacao beans.

- The Virginia Housewife, Mary Randolph, 1838. Along with one recipe for a drinking chocolate, Randolph includes a “chocolate cake,” which is a plain cake to eaten with chocolate.

- The Good Housekeeper, Sarah Hale, 1839. Published in Boston, it contains one recipe for drinking chocolate and another for an infusion of cocoa shells.

- Book of Household Management, Isabella Beeton, 1861. This mammoth, encyclopedic treatment of over 1800 recipes (in some cases, mere serving suggestions) is considered a quintessential cultural document of Victorian England. Chocolate and cocoa beverages are given very basic treatment. Its pastry and baking applications are limited to a soufflé, a chocolate cream set with isinglass, and cheekily, perhaps, a ‘recipe’ for a simple box of chocolates, for which Beeton advises, “Seasonable. May be purchased at any time.” Despite her spare coverage of chocolate, she does concede, “from the facilities of travel, we have become so familiar with the tables of the French, chocolate in different forms is indispensable to our desserts.”

- The Complete Confectioner, Pastry Cook, and Baker, Eleanor Parkinson, 1864. Originally published in Philadelphia in 1844 this revision of the 1849 edition contains surprisingly little use of chocolate. Among its “upwards of five hundred receipts” the only chocolate applications (cocoa in powder form does not appear) are simple drops and pastille confections, a chocolate ice cream, a ratafia infused with whole roasted cacao beans, a glazed biscuit, and decorative uses. Most interesting is the supplemental material Parkinson offers on the chocolate making process and her recipe for a sweetened chocolate, specifying a blend of preferred cacao origins.

- Handbook of Practical Cookery, Pierre Blot, 1868. Blot is often referred to as one of the country’s first ‘celebrity’ chefs, opening the first French cooking school in New York. In addition to guidance on chocolate and cocoa beverages, Blot offers chocolate bavaroise, soufflé, ice cream, eclairs, a type of macaroon, and several creams and custards. There are no confections, nor any use of cocoa powder in desserts.

- Boston Cooking School Cookbook, Fanny Merritt Farmer, 1896. For comparison’s sake, a look at this wildly popular cookbook reveals that by the end of the 19th century chocolate had made inroads as a common household baking staple. This book includes several variations of drinking chocolate (including infusions of shell and nibs) and nearly twenty recipes featuring chocolate in fritters, cakes, pies, cookies, creams, icings, and candies.

Fire!

Walking from an early breakfast near City Hall one Saturday morning in September 1852, a young English-born illustrator named Thomas Butler Gunn was caught up in the commotion of a passing fire brigade carriage and followed it to a fire on Duane Street near Broadway. “It was at a Confectionary & French Chocolate Manufactory,” he writes in his diary. “The flames were raging within the top-most story & soon darted off of the casements, red and luridly wicked looking, volumes of dusky, murky smoke choking the clear fresh morning air and soaring up into the pure blue ether.” The fire consumed the factory and nearly destroyed the six-story building at 75 Duane Street, run by a short-lived partnership of Eugene Mendes and Nazaire Struelens. A fireman was killed and several bystanders were injured by falling bricks as the building crumbled. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports the fire originated in a “drying room,” further claiming that “sugar soon began to melt and came trickling through the interstices of the flooring and down the stairway, forming streams of liquid fire.” The story of the conflagration was printed in newspapers around the country.

Fires were common in 19th century New York City. The so-called Great Fires of 1776, 1835, and 1845 leveled entire neighborhoods; tightly packed wood-framed structures allowed them to spread rapidly. With no centralized fire department, competing volunteer fire brigades arriving at the scene of a blaze often added to the chaos. As increased mechanization shaped how chocolate was made, it also began to affect the working environment itself. Flammable raw materials and packaging, roasters, sugar kettles, coal furnaces fueling steam engines and the machines they powered all posed a risk of fire and other occupational hazards. From the fire at John Roosevelt’s chocolate mill at Golden Hill in 1736 through to the 20th century, I count nearly thirty fires and explosions among the city’s chocolate and candy factories. As the decades unfold, factories – and the workforce needed to run them – will grow. Future posts will further explore aspects of labor and what is known about daily life in the chocolate factory.

In Closing

Innovation in chocolate advances at a quickening pace in this period, leaving much more to be discussed. Join the conversation as Clay and I highlight some of these topics in greater detail on Thursday, July 1st in The Chocolate Life room on Clubhouse. Follow along on this six-part series by reading an introduction to the series and the first installment digging into the rich history of chocolate in New York City.

Featured Image Credit: Broadway, New York, from Canal to Grand Street, West Side, Julius Bien, 1856. Public Domain, Retrieved from Metropolitan Museum of Art.