A Golden Age: Chocolate in New York, 1850-1900

Corresponding to a chocolate “boom” experienced on a global level, this period also establishes New York City as an epicenter for chocolate production and consumption in North America with the emergence of several prominent, large-scale manufacturers.

From a survey of chocolate products available to consumers in an 1892 publication that “represented very nearly all the brands obtainable at the time,” one gets a clear snapshot of the chocolate industry at a time when, “the variety of preparations offered to American consumers is certainly very great.” By the 1890s the world was in the throes of what some have called the first great chocolate “boom.”

We might look back at this moment in time as a weigh station of sorts, an assessment of how chocolate evolved from the previous century, and how those trend lines would develop into what we think of as “industrial” chocolate in the 20th century.

How Pure is Your Chocolate?

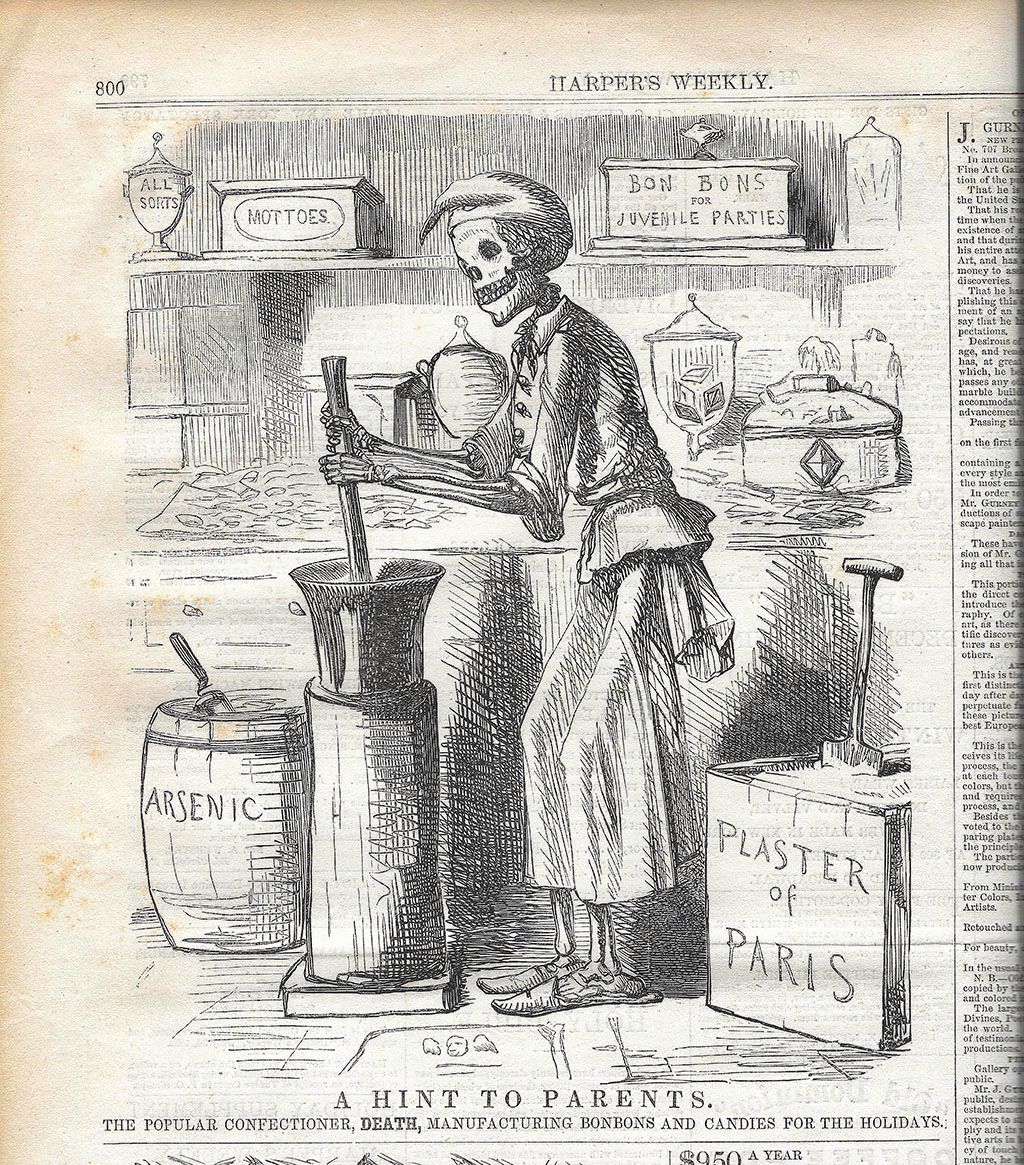

Part market study, and part scientific treatise on the composition and manufacturing of these chocolate products, the publication was born out of emerging ideas about consumer protection amid the growing industrialization of food production. Under the subtitle, Coffee, Tea, and Cocoa Preparations, this study of chocolate and cocoa was the seventh part of a broader investigation colloquially referred to as Bulletin 13. The reports were compiled by the chemistry division within the United States Department of Agriculture, established thirty years prior by Abraham Lincoln. The full title of Bulletin 13 was Food and Food Adulterants. Spearheaded by USDA chemist Harvey Wiley, the work was in response to decades of alleged malpractice in a virtually unregulated food system – from meat and dairy to highly processed products like chocolate and cocoa.

While today we enjoy manufactured food products like chocolate with a degree of confidence and trust in its listed ingredients, in the 19th century chocolate may have contained starches, colorants, and inedible fillers from cocoa shell to brick dust. Wiley’s efforts, begun in the 1880s, would ultimately lead to the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

Created were mechanisms to enforce greater transparency and standards of identity to establish a baseline of wholesomeness and quality not just in chocolate, of course, but for all processed food products.

A year before Milton Snavely Hershey began plotting his own chocolate business and seven years before launching what would become his iconic bar, New York’s makers dominated the market in 1892.

Roughly half of the dozen or so domestic brands included in the investigation, purchased from the shelves of grocers and druggists, were manufactured in New York City: Maillard, Huyler’s, Rockwood, Hawley & Hoops, and Runkel were the most prominent, alongside Whitman and Wilbur from Philadelphia, and, of course, Baker in Boston. An increasing number of imports had been entering the market since 1850, among them: from Britain, Epps, Fry, and Rowntree; Germany’s Stollwerck; Dutch firms Van Houten, Blooker, and Bensdorp; Menier, the most popular French brand. In addition to laboratory analysis, the survey offers a glimpse of the consumer chocolate experience in the 1890s, detailing the names of these products, how they were packaged, and their retail prices.

What Did Chocolate Cost?

If we were chocolate shopping on a budget in 1892, we might pick up a four-ounce bar of Runkel’s Vienna Sweet Chocolate for six cents (roughly valued at $1.80 today, or just over $7 per pound). A one-pound package of Huyler’s Family Chocolate sold for 40 cents (nearly $12 today), and for splurging, we might pick up the Triple Vanilla Chocolate made by Maillard for 75 cents a pound (in 2021 it would sell for $22). Menier’s chocolate, imported from France, competed with domestic brands at 60 cents per pound. And for a whopping $1 a pound (almost $30 today) one could enjoy a block of La India Vanilla Primera, manufactured by Fullié & Company in Caracas, Venezuela, founded by a Swiss family in the 1860s. By comparison, coffee might cost 50 cents a pound ($15) and for a bag of flour we might expect to pay 4 cents a pound ($1.20) in a major city.

The most experienced male worker putting in sixty hours a week in one of the city’s chocolate factories may have earned wages up to $4 a day (almost $120 today); female workers might have made half that amount, and unskilled or entry level positions may have only brought home as little as 75 cents a day.

For the lowest paid workers – likely the young women packaging finished chocolate – the cost of that most accessible Runkel chocolate bar represented what she earned from a full hour’s work.

The Makers

Between the years of 1850 and 1900 I count over twenty-five chocolate and cocoa processors operating in New York City. A few became well-known brands, and others appear in records for a year or two and disappear into the haze of history. As chocolate continued to cross over into the confections trade, I’ve tried to maintain a focus on those working directly from the bean; while many of the larger chocolate manufacturers also produced a range of confections from bonbons to marshmallows and fruit gums, fewer small-scale confectioners were producing their own chocolate.

In the first half of the 19th century, we saw factories following the city spread as far north as Houston Street. The 1811 Commissioner’s Plan set in motion the decades-long project of plotting and paving the remainder of Manhattan with a grid of east-west numbered streets and north-south avenues. Felix Effray was one of the first chocolate makers to land on the grid, moving his factory a dozen blocks up Broadway to East 9th Street around 1860. Commercial activity and manufacturing would largely remain in lower Manhattan through the end of the century, but some of the prominent makers would build large factories in developing neighborhoods.

The Huyler factory stood just north of Union Square on Irving Place, Maillard would plant a flagship boutique and factory in what would become the Flatiron District, and the west-side Runkel facility operated until the 1930s on the site of what is now the recently erected Hudson Yards development. As real estate became more precious, the 1890s saw some of the Manhattan makers moving across the East River into Brooklyn, and over the Hudson River into New Jersey.

The makers of this period are too numerous to profile in detail, but a closer look at the prominent brands of the day may help to put into perspective this “golden age” of chocolate in New York City.

Henry Maillard

Born about 1820 in the village of Mortagne-au-Perche in Normandy, Maillard (née Henri) grew up in the hospitality business as the son of innkeepers. Details of his early training in chocolate and confections are unclear, but he is known to have spent time in Paris as a young man. He sailed into New York in 1848 at the age of 29 amid a wave of other European makers. That his first factory appears the very next year suggests he had arrived with an eye for opportunity and some financial backing. The first advertisement to appear in The Evening Post announces, “Manufacturers of Patent French Chocolate and Confectionery, made by steam and newly invented machinery.” Located at 401 Broadway at Walker Street, the establishment included “an elegant Saloon for the reception of ladies” and served “Ice Cream, French Chocolate, Coffee, Sorbet… Oyster Parties and a great variety of cakes in Paris style…”

In 1853 the business moved up to 621 Broadway between Houston and Bleecker Streets and 160 Mercer Street, the former a hotel and restaurant, and the latter a connected factory. During this period, he develops a reputation as a caterer to the upper class and in February 1862 he prepared a presidential dinner at Lincoln’s White House. Holiday advertisements would list in detail the “choicest Parisian styles, such as new moulds for ice cream, mottoes, flowers, etc.” brought in from his frequent trips back to France. Among his chocolate products were, Chocolate de Sante, Chocolate de Famille, two varieties of Vanilla Chocolate, Spanish Chocolate, Chocolate Creams, and Chocolate Caramels.

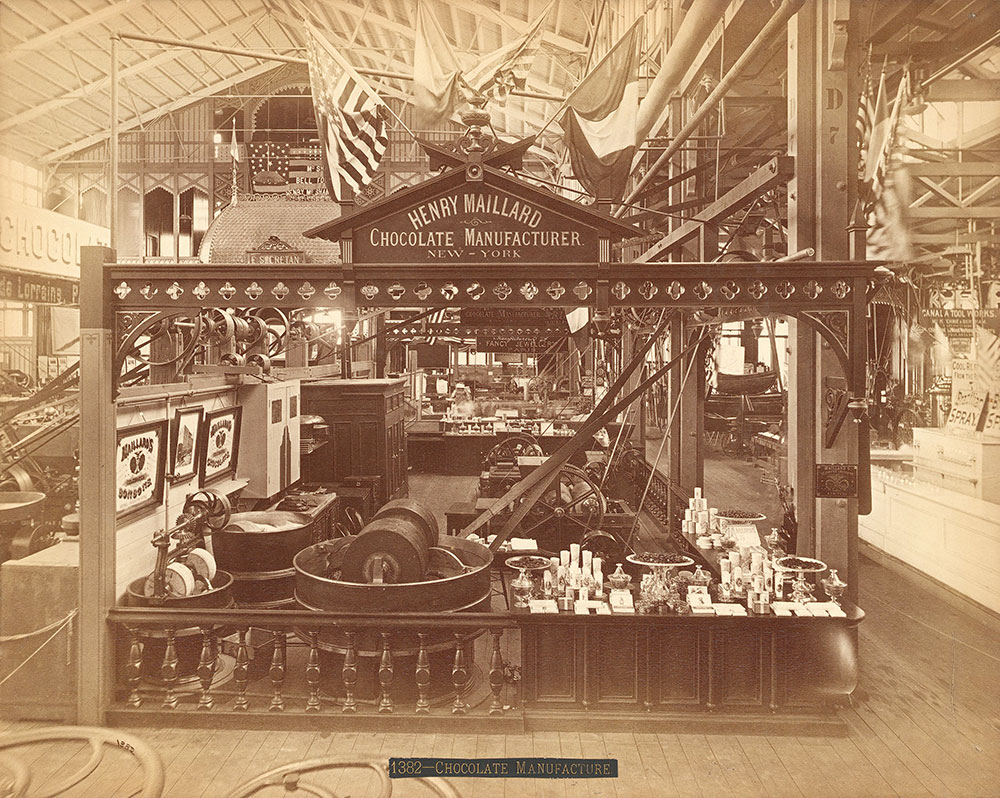

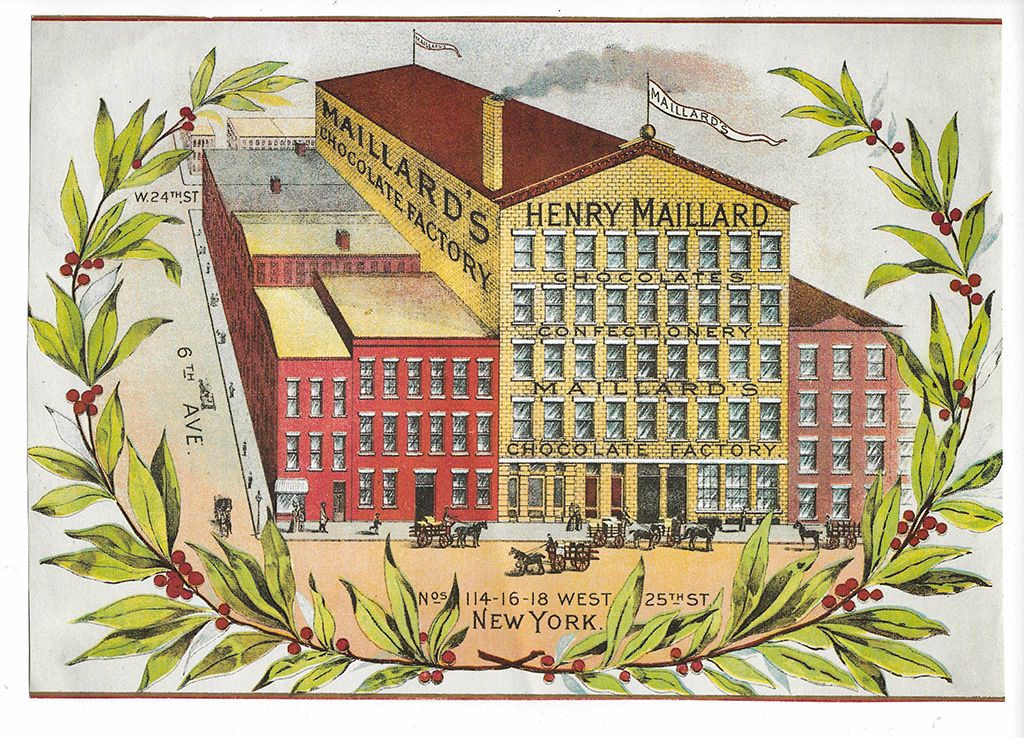

A fire in December 1872 destroyed the Mercer Street factory. According to The New York Tribune, “the ignition from a bag of hot cocoa shells the probable cause.” Despite a narrow escape by guests and staff, the hotel was spared significant damage. A year later Maillard reemerges with a lavish flagship store in the Fifth Avenue Hotel at 1097 Broadway across from Madison Square Park, and a larger factory running along 6th Avenue between 24th and 25th Streets. His display at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia included confectionery sculpture and several of his chocolate-making machines, which by this time would have been common in the city’s factories.

An 1885 profile describes, “the extensive chocolate and cocoa manufacturing establishment of Mr. Henry Maillard. The premises… affords an immense floor space every inch of which is utilized in the manufacture of the chocolates and cocoa for which this establishment is so famous. The interior arrangements are perfect. All the most improved machinery and appliances are at hand and a large force of skilled workmen are employed.” The article concludes with a glimpse of Maillard’s personal life, and that he, “enjoys all the happiness which wealth and prosperity can furnish. He moves in the highest social circles and is universally esteemed as an honorable and successful merchant, a liberal and public-spirited citizen.”

Henry retired to Paris with his wife Caroline in 1891, leaving the business to his son, Marie-Frédéric Henry Maillard who would steer the ship through the peak of the company’s renown. By 1900 Maillard products were sold from Vermont down to Atlanta, from New Orleans out to San Francisco. Henry died in 1900 and is buried at Montparnasse in Paris. For nearly five decades, Maillard represented the face of French refinement in New York’s chocolate culture.

Hawley & Hoops

John S. Hawley was a jack-of-all-trades who dabbled in several business ventures. Born in upstate New York in 1836, as a young man we find him in Texas and California, and among those who followed the silver rush in Nevada. Back in New York City by the early 1870s, he was employed by Wallace and Company, the established chocolate maker and confectioner at 29 Cortlandt Street. It’s in this period that Hawley also files a patent for something called the ‘elastic force cup’ – today we know it as the humble toilet plunger. It’s believed that the proceeds from the sale of this patent funded his first solo foray into the chocolate business.

Hawley’s Peerless brand chocolates and other confections were manufactured at 154 Chambers Street (more recently, the home of neighborhood fixture, Tribeca Hardware). One of his employees, Herman Hoops, born in New York to a German immigrant confectioner in 1855, became a partner in 1878. In the early 1880s, Hawley & Hoops developed the “A No. 1 Brand” and became one of the first brands of any kind to create a kind of pop culture licensing campaign though their collaborations with illustrator Palmer Cox. An 1884 advertising trade card was the first to to feature Cox’s popular Brownies cartoon characters – perhaps the 1880s equivalent to placing Reese’s Pieces in the movie E.T. or Bart Simpson hawking Butterfingers.

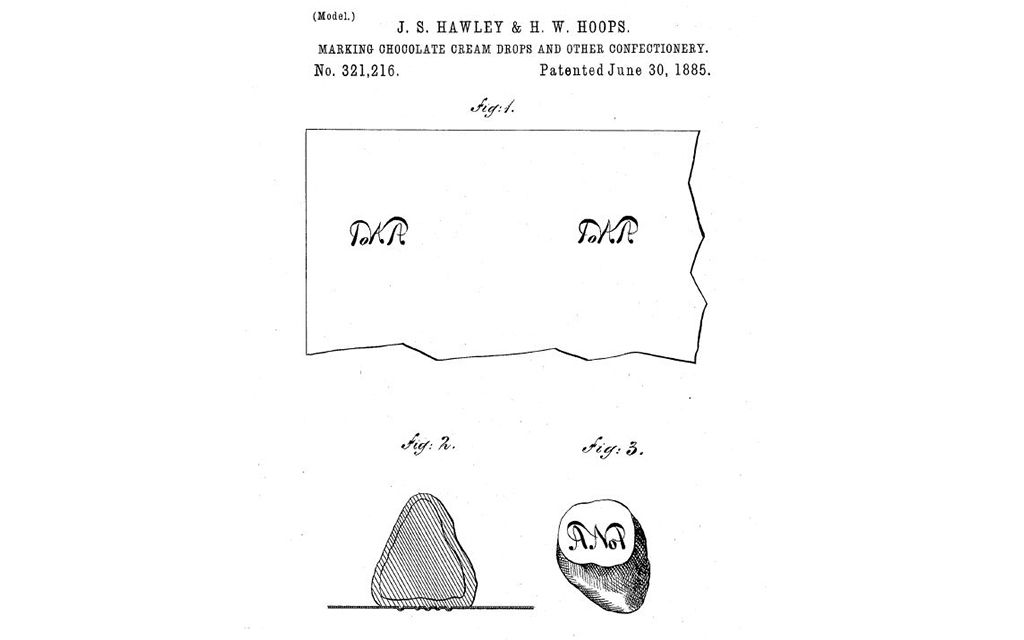

In 1886 Hawley & Hoops built a large factory just south of Houston Street between Mulberry and Lafayette Streets; it is the oldest of the few chocolate factories still standing in New York City. The Nolita building is now home to a branch of the public library and loft apartments owned by celebrity tenants. At its peak the factory employed 800 people. In addition to chocolate and cocoa products, the factory pumped out a variety of candies. Hawley & Hoops was among those experimenting with novelty molded chocolates and were well-known for chocolate cigars and cigarettes. The company filed several patents in the 1880s and 1890s, from candy-making machinery to toy chocolate whistles. Perhaps most interesting among them, a patent for embossed paper that transferred the “A No. 1” logo design onto the bottom of their dipped chocolate cream drops

By the late 1890s, Hawley left more of the managerial duties to the younger Hoops and diverted his energy toward philanthropic projects, eventually retiring to southern California. Hoops, his brother, and son would continue to expand the company into the 20th century.

Runkel Brothers

Born in the early 1850s in New Orleans to a German father and French mother with a garment business in the French Quarter, brothers Louis and Herman Runkel arrive in New York as teenagers. Departing from the family trade, the brothers began making chocolate in the Clifton neighborhood of Staten Island in the early 1870s. Their 1876 advertisement offered, “For sale, cheap – a five horsepower upright boiler and engine… now running in a chocolate factory,” marks the Runkels’ move from the island into lower Manhattan at 9 Maiden Lane where they produced chocolate and cocoa for two years.

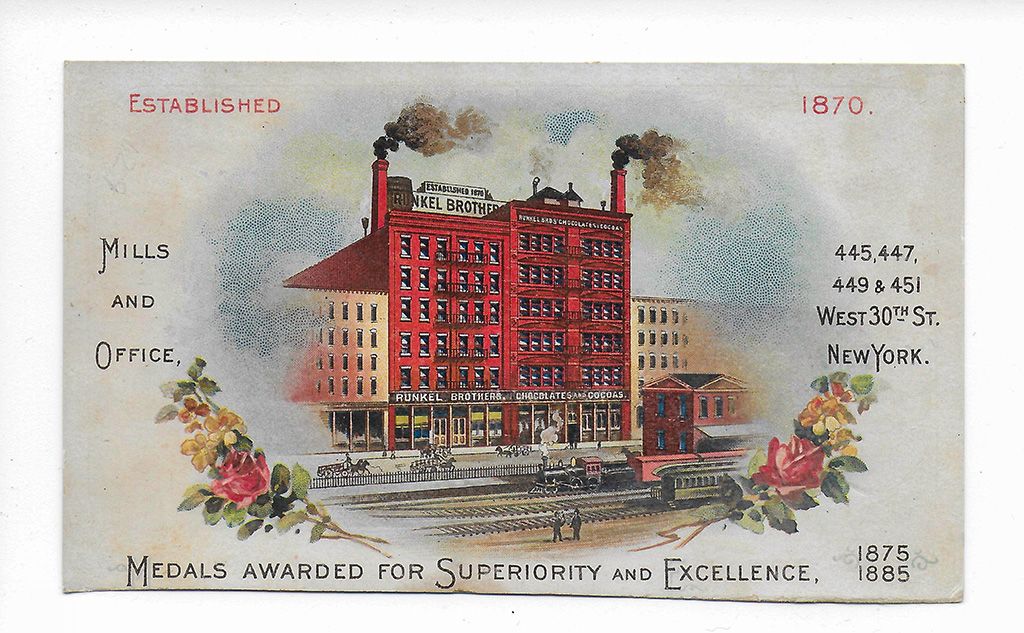

The brothers then operated a factory uptown at 230 West 30th Street near today’s Penn Station. The first of three major fires afflicting the company over a span of three decades occurred in December 1879. After moving around the corner to 328 7th Avenue, a second fire partly damaged the building in April 1885 (arson was the suspected cause). The move to 445 West 30th Street in 1888 would result in a permanent headquarters for the Runkels, where a factory remained into the 1930s; it was rebuilt after a three-alarm fire in 1901 destroyed the original six-story structure.

Runkel became known for their Red Ribbon, Vienna Sweet Chocolate, and Chocolat des Marquises, among other proprietary bars and cocoa powder products. Fully embracing the Victorian-era craze for advertising trade cards, the company made full creative use of the medium in the 18880s and 1890s. Runkel’s tagline was, “I want it, I’ll get it, right in it,” and eventually shortened to, “Right in it.”

A popular consumer brand, Runkel Brothers was also one of the first to widely market wholesale liquor and coatings to smaller confectioners. By the late 1890s, success in the chocolate business would increasingly depend on the capacity to produce volume.

Huyler’s

John S. Huyler was born in New York City in 1846. His father, David, operated a bakery in Greenwich Village and the family lived over the store. Huyler went to work at the family shop around 1863; after a time he began making a line of his own soft molasses candies. With the help of his father, he moved to a small retail store and factory at 863 Broadway just north of Union Square in 1876. The Huylers employed a strategy similar to Felix Effray’s in 1849; to attract foot traffic in the busy neighborhood, he installed a taffy pulling machine in the window of his shop.

He moved to a larger factory space at West 11th and Bleecker Streets, but quickly outgrew it. By the early 1880s Huyler was supplying additional branded retail shops in Brooklyn and the Northeast, and his product range came to include chocolate and cocoa. Outgrowing the West Village factory, Huyler expanded again in 1883, to 64 Irving Place at 18th Street. With additions over the years to the original six-story building (and repairs after fires in 1889 and 1907), the factory would operate for nearly five decades.

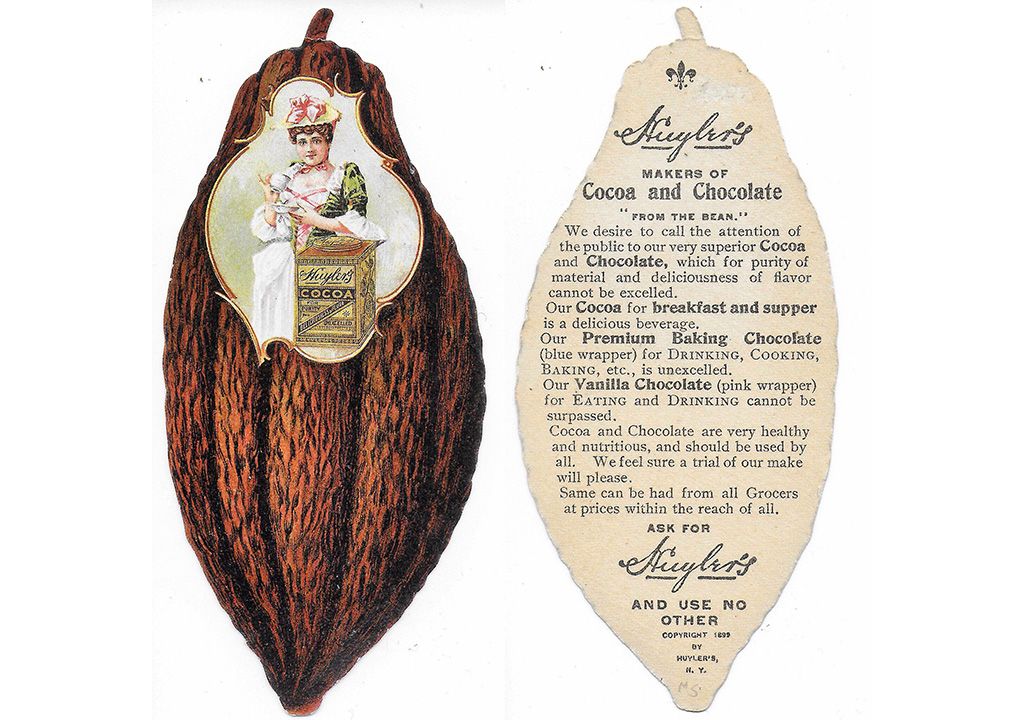

The signature chocolates Huyler sold were commonly known by the color of their wrappers – blue for Family Chocolate formulated for drinking and pastry applications, and their Vanilla Chocolate for eating wrapped in pink. The strong visual association he created even led other makers to imitate with their own color-coded bars; into the early 1900s Runkel Brothers sold a vanilla-flavored bar in similar pink packaging.

Huyler’s products were also notable for the cacao pod imagery and references to cacao beans in their advertising. An 1899 trade card was die-cut in the shape of a pod. Magazine ads claim that, “importations of cheap (low grade) beans have increased,” but assured customers, “we have used and are using the same quality of beans as always: the best only.” The term “bean-to-bar” is often believed to have been coined in recent years to identify small-scale makers by scale, method, or overall philosophy. In the 1890s, Huyler’s often used the phrase “from bean to cup” to connect the finished product with the raw material. The company may have been inspired by the title of an important book on coffee, From Plantation to Cup, written by Francis Thurber in 1881.

Chocolate and confections made John Huyler a millionaire. By the time he died in 1910 at age 64, he had built an empire with over fifty candy shops across the country and, along with the Irving Street factory, employed roughly 2,000 people.

Rockwood

Wallace Thaxter Jones was born in 1849 near Boston, and arrived in New York City by 1870. Employed for a time by the Duryea Starch Company, in 1872 we find him at the European Chocolate Company run by John Vansaun at 92 Bleecker Street. Vansaun had previously made chocolate in partnership with French chocolate makers Eugene Mendes and Evariste Martin at 165 Church Street. In 1875, Jones was working with chocolate dealer John Bassford. He worked with Henry McCobb – a colleague from his time with Vansaun.

All of this experience culminated with the founding of the Rockwood Chocolate Company in partnership with William Rockwood. Though the company bore his William’s name, Jones seems to have contributed the chocolate know-how. They established a factory at 468 Cherry Street, which today would lie in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Whereas chocolate makers like Maillard, Hawley and Hoops, and Huyler’s owed their success as much to candies and confections, Rockwood, like Runkel Brothers, largely specialized in chocolate and cocoa products. The company’s rapid expansion would lead to a move to Brooklyn in the 1900s. Just as New York City’s other prominent makers began to see a decline, Rockwood would thrive to become, for a time, the second largest chocolate manufacturer behind Hershey. We’ll continue to track Rockwood’s rise as the series continues.

Henry McCobb

Though not remembered for size or longevity, the company run by the quirky and mysterious Henry McCobb is worthy of honorable mention. Born in 1851 in Portland, Maine, McCobb attended Brown University and is thought to have started manufacturing cocoa and chocolate upon his return home in 1873. He appears in New York working with Vansaun in the mid-1870s. A trademark for his “Owl Brand” is registered in 1879 and we see McCobb making chocolate under his own name at 25 Vandewater Street near City Hall in 1880.

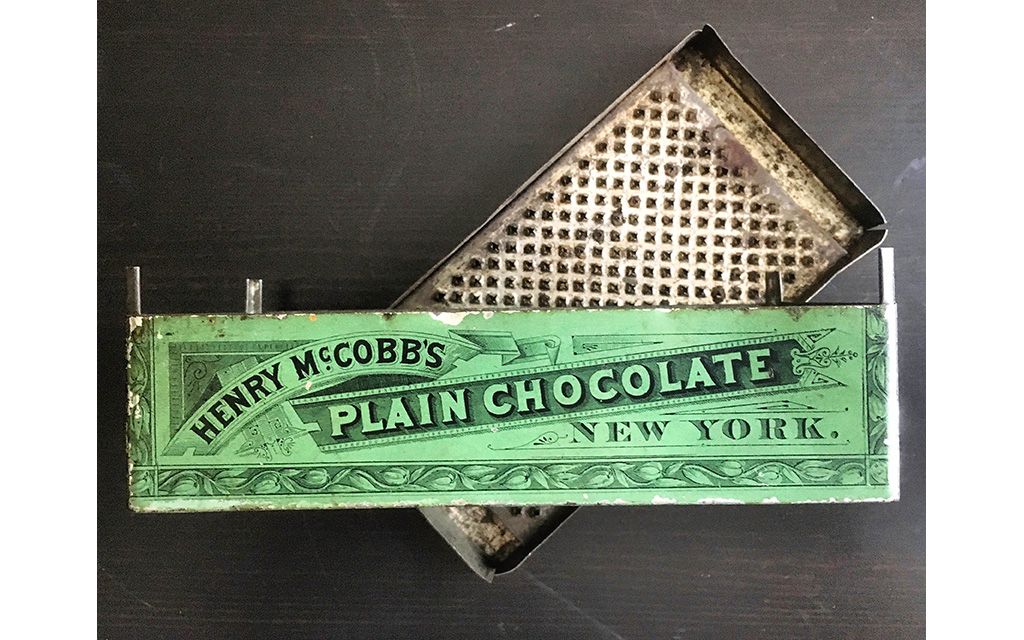

A patent filed by McCobb reminds us that even this late into the 19th century, given chocolate’s role in confections, blocks were still commonly grated for preparing drinking chocolate. His 1882 patent for a rectangular tin box holding a pound of chocolate included a built-in grater in the lid.

By 1885 McCobb moves uptown to 309-311 East 22nd Street, between 1st and 2nd Avenues; his factory was next door to the chocolate-making facility operated by Philander Griffing and Claude Crave. The McCobb and Owl Brand products included Plain, Sweet, and Havana Sweet Chocolates in addition to cocoa, broma, and bonbons. The chocolates had a national reach, and over 200 pounds of his chocolate happened to be part of the inventory of the ill-fated Greely expedition to the North Pole in the early 1880s.

Wallace T. Jones worked with McCobb briefly before leaving to form the Rockwood Chocolate Company in 1886, and in 1890 McCobb assigned the lease of the factory to his brother-in-law banker Louis Mendham for unknown reasons. Soon after, a partnership of Crave, Griffing, and Evariste Martin had taken over McCobb’s factory. Just as quickly as he appeared in New York City a decade prior, he disappears from records almost completely.

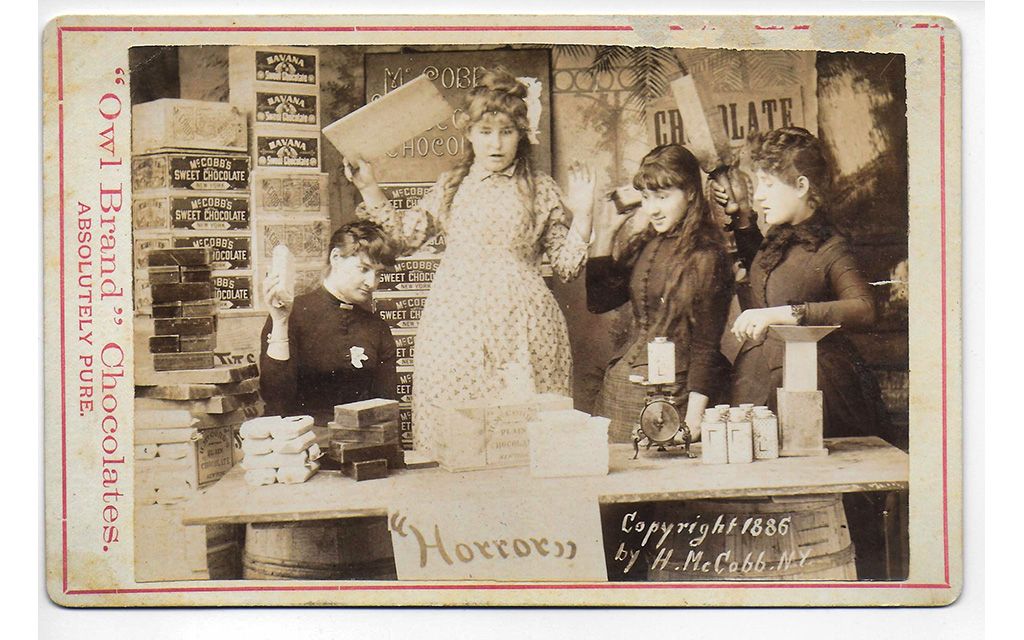

What makes McCobb fascinating to many is the surviving ephemera of his brand – interesting (and occasionally bizarre) photographic prints (some combined with illustration) that did not echo the typical illustrated themes of Victorian era trade cards. The year 1886 appears to have been especially productive, as that date is marked on many of the cards that survive – some of which depict McCobb himself. The card below was from a series, “200 Scenes in a Chocolate Factory.”

Hershey

After gaining some confectionery experience first in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania and then chasing opportunity in Denver, Chicago, and New Orleans, 26 year-old Milton Hershey arrived in New York City in 1883. He furthered his training at the newly built Huyler factory on Irving Place, where he stayed until 1885. Hershey opened a small confectionery shop at 6th Avenue and 42nd Street (later moved to 428 West 42nd Street), where he worked out many of the ideas and recipes collected during his training. Looking for a product that would put him on the map, it’s believed Hershey bet on cough drops as his golden ticket, and in 1886 the business failed. He returned to Pennsylvania and founded the Lancaster Caramel Company – Milton’s third business venture, and the one that finally stuck.

The familiar story then places Hershey at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where, upon seeing the German firm J.M. Lehmann’s suite of chocolate-making equipment on display, is inspired to pursue chocolate making in earnest. He reportedly told his cousin, Frank Snavely, that, “Caramels are a fad but chocolate is permanent. I am going to make chocolate.” A January 1894 letter from Lehmann’s importing agent in New York, Bothfeld & Weygandt, follows up on conversations, “with you yesterday in reference to an outfit of machinery for roasting, breaking & hulling and grinding cocoa, as also a cocoa butter press, we beg to recommend the following machines…”

Had Hershey seen success with his 42nd Street candy shop it’s quite possible we would be counting him as one New York’s prominent makers, or perhaps he wouldn’t have leaned into chocolate at all. Though by 1903 he would be breaking ground in Derry Township for his factory (and the town that would bear his name), within twenty years he would return to New York City once again.

Foreign and Domestic

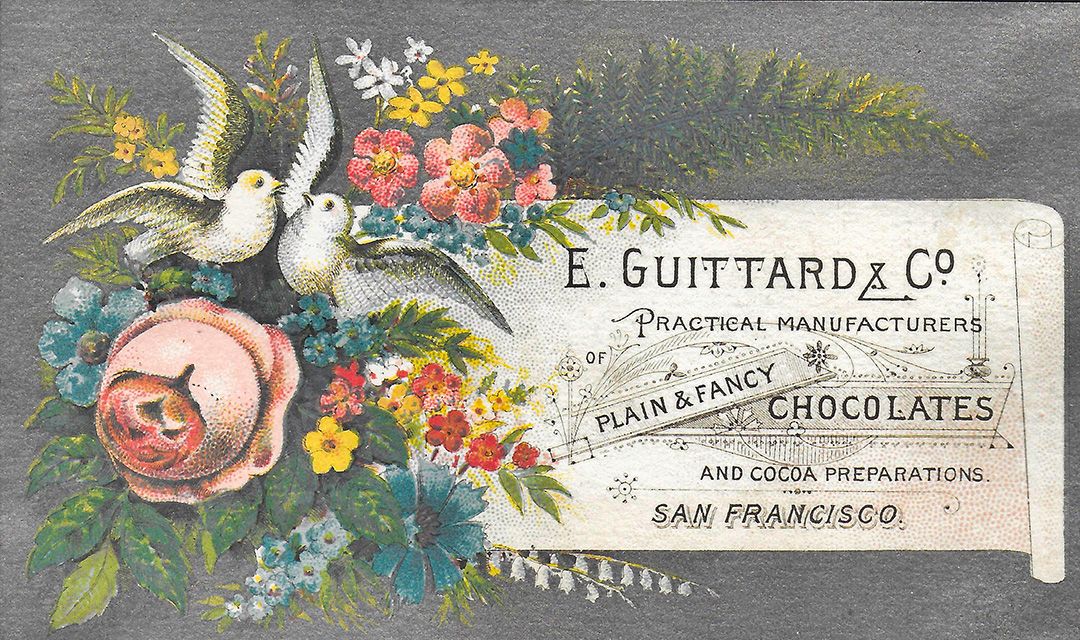

Of course, other prominent brands shared the market with the New York manufacturers at this time – the likes of Walter Baker and Webb in Massachusetts (Baker acquired Webb in 1881), or Stephen Whitman and Henry Oscar Wilbur in Philadelphia. Chocolate makers had arrived in San Francisco as well. Leaving Lyons, France in search of fortune in gold, Etienne Guittard never struck it rich, but he did open a small factory and store on Sansome Street in 1868. Italian-born Domenico Ghirardelli arrived earlier at the start of the Gold Rush, but quickly saw more opportunity in selling supplies to the prospectors; he began making chocolate in San Francisco in 1852.

Gary Guittard, the fourth generation to run his family’s business, has suggested the likelihood that flavor or stylistic differences existed between makers on the East and those in the West. Long before the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, we observe that manufacturers in the East used more Caribbean, Venezuelan, and Brazilian cacao beans, whereas the West Coast makers by proximity had better access to Ecuador, Peru, and the Pacific coast of Colombia.

Menier’s chocolate was regularly appearing in New York and elsewhere by the 1850s. The son of founder Antoine Menier, Emil-Justin grew the business to become the largest French manufacturer. In this period, the firm developed a presence at origin in Nicaragua, built a London factory, and transformed the small village of Noisel into a “factory town” to house its workforce.

By 1884, Félix Bonnat began making chocolate in Voiron.

From Britain, the century-old Fry Company in Bristol had a presence in North America. The opening of John Cadbury’s Birmingham store served as foundation for another prominent maker. Son George expanded the chocolate business, and perhaps inspired by Menier, established the Bourneville factory town in the 1880s. Meanwhile, in York, Henry and Joseph Rowntree were growing their cocoa and confectionery business in the 1860s.

Cacao by the Numbers

In 1890 a little over 9,000 tons of cacao entered the United States, primarily through the port of New York, up from 5,000 tons in 1885. Beans from the British West Indies, Dutch Guiana, and Brazil led among imported origins, followed by Venezuela, Ecuador, and Haiti. West African exports (apart from Sao Thome and Principe whose crop largely went to the UK and Europe) were virtually non-existent in the early 1890s, though the upward trend of production in the British Gold Coast and French Cote d’Ivoire colonies beginning in the early 1900s would lead to their current dominance today.

New York prices in late 1891 ranged from 13 to 15 cents ($3.85 to $4.44) per pound ($8.47~$9.77/kilo) for Caracas, Trinidad, Bahia, and Guayaquil cacao to 8 cents ($2.37/pound or $5.21/kilo) for Santo Domingo beans. Over 800 tons of finished chocolate and cocoa products were imported in 1890. While some raw cacao in this period was technically exported from New York by way of transit, virtually no finished chocolate was shipped abroad; almost all of the cacao imported supplied domestic demand. In 1900 annual imports doubled to roughly 18,000 tons. Increased demand drove these numbers, of course, but the removal of import duties also made the American market attractive; low prices further enabled manufacturers to expand increasing the accessibility of chocolate.

Tools and Technology

By 1850 grinders and melangeurs run on steam engines had become common in chocolate factories. Pressing liquor by various means (perhaps based on Van Houten’s hydraulic press) fractioned cocoa butter from the solids resulting in a range of powdered cocoa products and broma. the creation of modern eating chocolate was accelerated by the Fry Company’s reformulating with additional cocoa butter. An increasing variety of sweetened chocolates and chocolate-flavored sugar confections blurred the line between the realms of specialized chocolate makers and candy makers. Continued efforts of refinement from abroad would further shape chocolate.

Mechanization, diversified product range, innovation, and competition created an atmosphere I have come to refer to as a golden age of chocolate manufacturing in New York, with more makers in this period than any time before or after.

Milk Chocolate

The next most meaningful breakthrough was the effort to combine chocolate with milk. For all we know, Swiss candle maker Daniel Peter may never have made a name for himself in the chocolate business had he not married into the family of François-Louis Cailler. Cailler established his factory near Vevey in 1819, after training at the famed chocolate house Caffarel in Turin. Ten years after Cailler’s death – his company then in the hands of his wife and sons - Peter married Fanny-Louise Cailler, and by 1867 had taken over his in-laws’ business.

Determined to solve the inherent problems of adding watery milk to chocolate, the popular legend purports that his experiments were aided by friend and neighbor, German-born Henri Nestlé. Part chemist, part food scientist, Nestlé’s primary focus was milk processing – not chocolate making – and had developed stable condensed milk products and infant formula, or farine lactée. By 1875 Peter’s milk chocolate had been perfected, and soon after, Nestlé sold his own company shortly before his death in 1880.

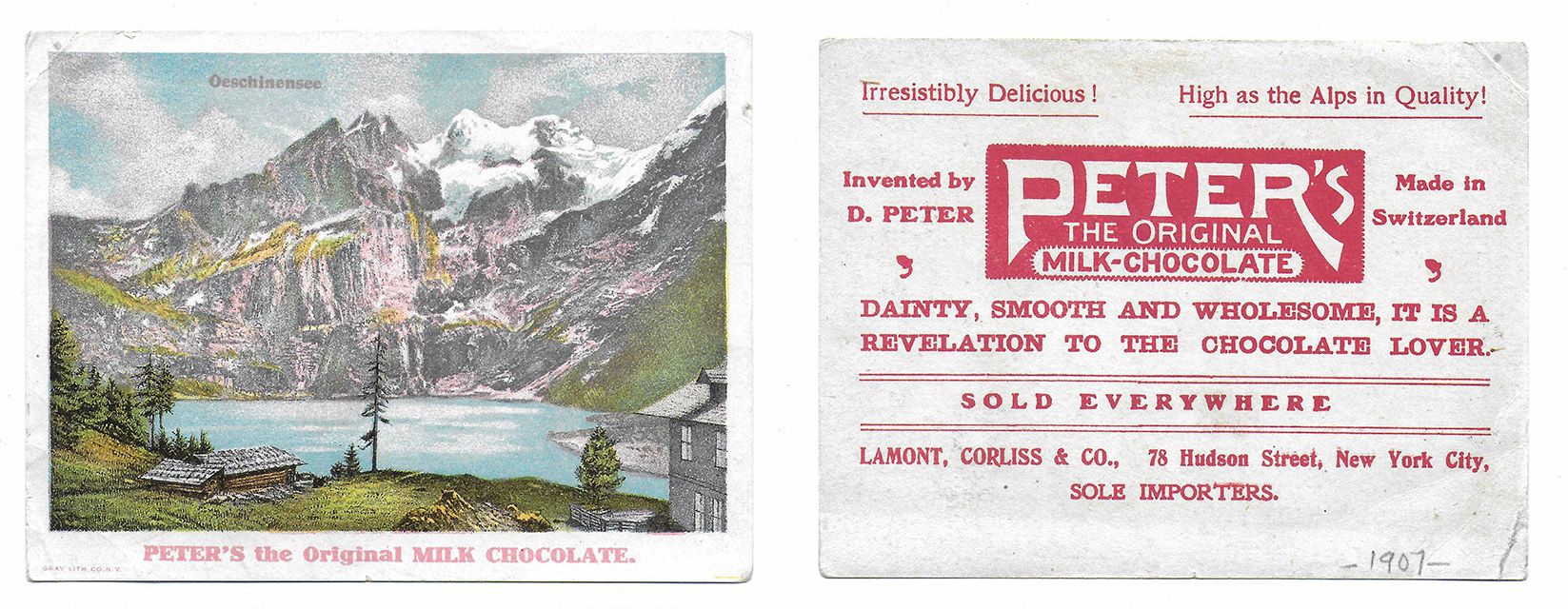

Peter’s milk chocolate had arrived in the United States around 1900, via importer Lamont, Corliss, & Company headquartered on Hudson Street in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood. The company established domestic manufacturing of the Peter’s brand by 1908 in Fulton, New York in close proximity to dairy farms. Though Henri Nestlé’s contribution to the collaboration with chocolate maker Daniel Peter was important, our coupling of milk chocolate and Nestlé is the result of rivalries and mergers and acquisitions that would play out into the 20th century. Needless to say, of all the names that would anchor the roots of the company – Cailler, Peter, Kohler (and even milk rivals George and Charles Page) – it was Henri’s name that would stick, as its supremacy in milk products overshadowed its confectionery business.

Nestlé is today the world’s largest food processor. Until its restructuring in the mid-20th century, the chocolate brands under the Nestlé umbrella remained under Lamont & Corliss management. Daniel Peter’s name lives on in the form of bulk chocolates produced by Cargill, who purchased the brand in 2002.

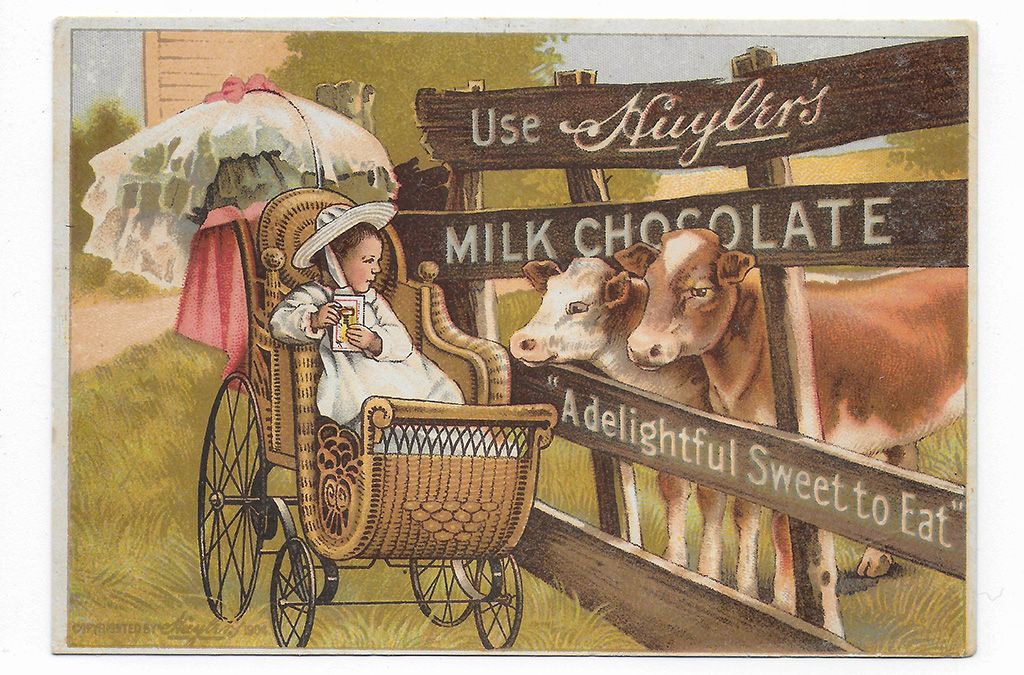

Milk chocolates – Swiss or otherwise – do not appear among the products listed in Wiley’s Bulletin 13 and New York’s chocolate makers don’t seem to have started making it until the imported brands arrived in the early 1900s. In this respect, Hershey beat the competition to the punch; the first bars resulting from his process were released in 1900. Maillard, Huyler, and others eventually responded with their own. Runkel boasted its Crème de Milk Chocolate was “essentially a food, and to be eaten as such,” and that “there is all the food value of a pound of meat in a 5-cent cake.” Manufacturers marketed the bars with images of cows and pastoral settings, perhaps adopting the marketing strategy used by Swiss makers to evoke bucolic Alpine serenity.

Initially touted for its healthy wholesomeness, milk chocolate would soon become the primary vehicle for candy bars and condition the taste of chocolate for generations to come.

The Conche

The final breakthrough that would elevate chocolate at the end of the 19th century occurred in the factory of another Swiss maker. Rudolf Lindt trained at the Lausanne factory run by the sons of Charles-Amédée Kohler, who began making chocolate in the 1830s. After a two-year apprenticeship in the 1870s, he opened his own shop in Bern. The story around the development of Lindt’s conche in 1879 sways from one of patient deliberation to happy accident.

If we separate the conching machine from the conching process, perhaps both are true. The invention of a new type of mixing apparatus – so-named for its resemblance to a conch shell – was certainly intentional. The process – extended mixing over a period of days distinct from refining – may indeed have been the result of a mistake by Lindt or his workers. Either way, the agitation, heat, and aeration the mixing provided, to quote one observer, “ennobled” the finished product.

Now performed in a variety of machines, those elements help develop flavor and texture by removing moisture and volatile acids, while also dispersing and coating the solid particles in fat. In some machines, such as Lindt’s original longitudinal design, the process may also smooth out the geometry of those solid particles. A closely guarded secret for years, the factories of New York installed banks of these conching machines, or “day mixers” in the early 1900s. A clue to the early use of a conche at Maillard is their product, Chocolat Fondant Lacté; the French word for “soft” or “creamy,” fondant was used to describe the improved texture created by the conching process.

A Temperamental Product

One more piece of chocolate’s technological puzzle involves the tempering process. As formulations began to incorporate more cocoa butter resulting in higher fat contents, its workability increased, but so too did the need to temper the chocolate. Tempering stabilizes that polymorphic cocoa butter into one ideal crystal structure for optimum snap, shine, and mouthfeel. Improperly handled, or exposed to temperature fluctuations, the solid fat crystals melt and recrystallize in unstable forms, marring the bar with a whitish “bloomed” appearance. Given the manufacturing and storage conditions of the day, one might assume much of the chocolate made in the 19th century suffered from this defect.

Emil Menier is said to have once turned this flaw into his advantage, the story retold by The New York Times in 1881, after Menier’s death.

“Among the many anecdotes connected with the late M. Menier… is one curiously exemplifying the ease with which a ready wit may convert a seemingly irreparable mishap into a source of profit and renown. It appears, that some years ago a large quantity of cake chocolate. which bad been for a considerable time "in stock,'' stored away in Menier's warehouses, was found, when required for sale, to have turned white. The manufacturer was in great perplexity as to how he might remedy so untoward an accident.” Menier then decided to advertise, “his chocolate as being the only chocolate in the world susceptible of turning gray through old age."

The story claims, "An enormous demand for the 'white chocolate' was the result; the whole damaged stock was sold off at a top price, and, if we may believe… there are still thousands of chocolate consumers in France who exhibit a decided preference for that particular description of the 'chocolat Menier' the cakes of which, when broken, exhibit a grayish hue throughout their entire substance.”

This Barnumesque marketing ploy aside, it does beg the question – given all the advances in chocolate over the 19th century – who was the first to understand and implement a tempering process?

The polymorphic nature of some fats was observed but barely understood in the mid-1800s. There are a few who have suggested Jean Tobler (creator of the iconic Toblerone bar) deserves credit, rounding out a sort of Swiss trifecta of innovation alongside milk chocolate and the conche. I have not yet seen enough corroborating evidence to confirm the claim. Rather, it is more likely decades of gradual accumulated knowledge among a generation or two of makers that would ultimately lead to the development of controlled tempering processes and machines at the turn of the 20th century.

This topic will be explored in depth as the series continues, but the methods and terminology of tempering that chocolatiers use today were codified much later, beginning with research published in the 1960s, particularly the work of Kåre Larsson, R.L. Wille, and Edwin Lutton (with further refinements, and perhaps some controversy, by others in the years since).

Homegrown Innovations

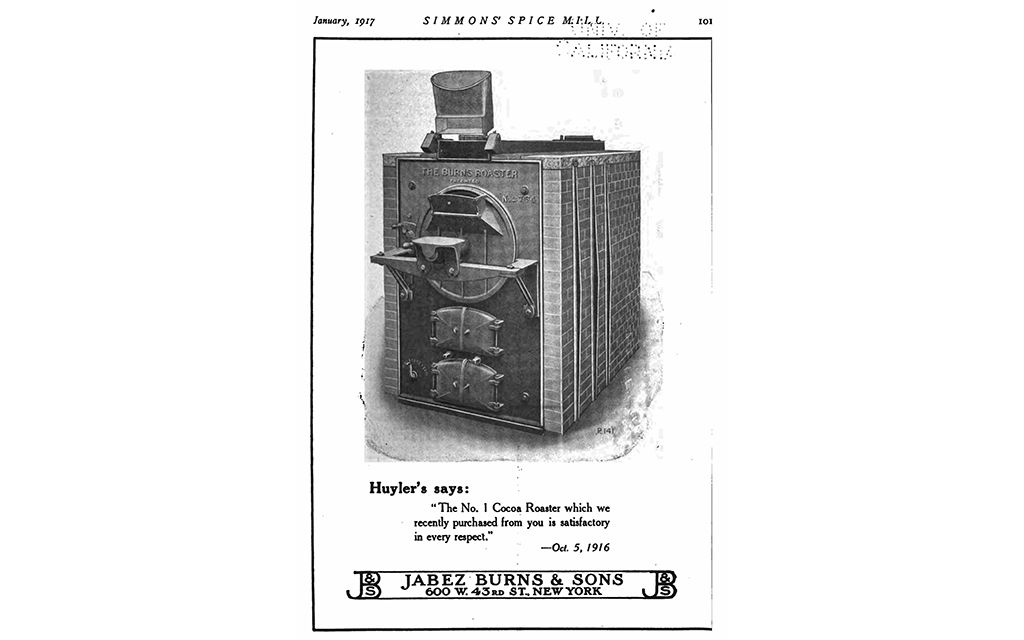

Buried in the gossip column of the New York Times in June 1890, a prominent but anonymous confectioner quipped, “With all the inventive genius of Americans,” said a prominent confectioner, “it is strange that until very recently all the cocoa beans roasted here by the big chocolate manufacturers have been roasted in the bungling machines imported from France and Germany, as our own roasters have been found entirely unsuited for this class of work.” The chocolate maker then explains the finer points of dampers and venting before announcing, “This has at last been achieved by an American, who has invented a roaster that with this attachment will roast perfectly 500 pounds of cocoa beans in fifty minutes.”

New York City’s millwrights were adapting alongside its chocolate makers. Thomas Gage and Chris Abele offered to chocolate makers custom millwork, roasters, and line shaft installation from their workshops in the west side Chelsea neighborhood. Charles Ross advertised “the best burr stone mills in the world” from Williamsburg, Brooklyn. It was British-born Jabez Burns, however, who had impact within the chocolate industry on a national level. Establishing his first factory on Worth Street in the 1860s, Burns specialized in coffee roasting and milling, as well as spice grinding (Burns also founded a trade journal, The Spice Mill, which published into the 1920s).

The business transferred to down to sons Robert and Jabez Jr.; expansion to a larger factory on 11th Avenue in Hell’s Kitchen coincided with the boom in the city’s chocolate manufacturing. They adapted their coffee roasters for cacao and added raw bean cleaners to their line. Burns roasters would operate in the New York factories of Auerbach, Bischoff, Greenfield, Heide, Huyler, Knickerbocker, Loft, Rockwood, Runkel, and Wallace among others; Baker, Hershey, Ghirardelli, and Wilbur were among the many others using their equipment.

Though the chocolate to connection is now largely overlooked, the Burns name survives as an independent American subsidiary of the German coffee roaster firm Probat and has revived some of the cosmetic features of the original 19th century designs.

Culture & Commodity

This golden age of manufacturing in New York City also transformed the culture. A wider range of products and applications made chocolate far more accessible. As this series enters the 20th century, we’ll explore in more detail the various forces that shaped chocolate’s role in daily life. Many of our complex, modern-day associations with chocolate emerged from this period, as did our preferences and perception of its role as part of a larger food system.

The “boom” that began in the 1880s would continue until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. The geographical spread of cacao cultivation and the rapidly increasing volumes produced firmly established chocolate and cocoa as a commodity of global importance and created the supply chain we recognize today.

With all of the technological advances of the 19th century in place, the conversation turns to how the chocolate industry responds by exploiting the economy of scale. New York City’s manufacturers played a role in transforming chocolate in the golden age, and will find themselves transformed as they adapt with the birth of a consolidating industry in the decades to come.

The dialog continues on Thursday, July 8th in The Chocolate Life room on Clubhouse, where Clay and I will place these 19th century developments in greater context. Catch up on previous posts in this series, and listen in to the recorded podcasts of our conversations.