Chocolat Bahia 2022 – A Festival Photoblog

I return to Ilhéus in Southern Bahia after a five-year gap. This is the oldest of the Chocolat Festivals in Brazil – and the first since 2019.

Prelude Part 1

My July travel schedule was ... hectic? Nuts? Exhausting? All of the above?

Keep in mind that since March 2020 I had made only one international trip, in September 2021, to Nigeria.

In July, I made three international trips (Brazil, Colombia, Brazil again) totaling eighteen separate flight segments, with six overnight flights in total, including two back-to-back overnight legs that bookended a 15-hour layover in Panama City. And, I was on the ground in NYC less than 24 hours between the return from Colombia and heading back to Brazil.

I am also a couple of years older and I was recovering from a mild case of COVID that I caught in mid-June, so I started out on my travel adventures out of practice and in less than peak condition. That’s why this photoblog has been delayed.

Prelude Part 2

My first trip to Brazil was to Chocolat Bahia in Ilhéus in 2017. I was there as a member of the press and so participated in the official press program. This year I was working on behalf of the organizers and so my participation in the festival – and the visit overall – was less scheduled.

Sightseeing in Ilhéus

Back in 2017, the only “free” moments I had to see Ilhéus were with the rest of the press group. On this trip, I had all of Thursday before the 19:00 official opening of the show to fill as I saw fit. That meant walking (the best way to learn a city, IMO), as well as a visit to local markets.

Back in 2017 I was staying in a hotel along the southern beaches. This year I was much closer to the convention center, and the northern beaches are not nearly as nice as those on the other side of the bridge. Still, I woke up every morning before sunrise to see if I could catch anything near as spectacular as the sunrise I caught back in 2017. No luck – but still quite pretty.

I would visit the Central Market (the Mercado Municipal) on the last morning of the trip – but on this, after visiting the site of the festival to orient myself, my destination was the Mercado Artesanato.

[L] Entrance; [C] Interior; [R] the Cacau Café

The Mercado Artesanato is a version of markets I have visited all over the Americas and Caribbean. It reminded me most of the Bazar Artesanal Mexicano in Coyoacán in Mexico City. Like many of these markets, the variety of offerings here is limited and repetitive – but what I was looking for was food items, and I found a lot to interest me. Spice blends, hot sauces, sweets – including a wonderful cocada maracuja (passion fruit-flavored flaked sweetened coconut), and something I had never seen before crystallized jenipapo. I tasted much, and purchased much, too, for gifts.

I had never tasted anything like it – and I did not like it one bit. I think this is one of those things you have to grow up eating to like. Tasted to me a lot like (a slightly off) young Parmesan.

[L] The Bataclan; [C] An old church; [R] The Casa de Cultura Jorge Amado.

As you can see from the above photos, it was a stunningly brilliant clear day for walking around – in the upper-20sºC – so warm, but not too warm. The Centro Historico in Ilhéus is a small but vibrant district with many old buildings, small parks, and busy commercial streets filled with vendors selling all manner of items from carts. One thing I was looking for but could not find was fresh jabuticaba, perhaps my favorite Brazilian fruit after cacau and cupuaçu (T. Grandiflorum) pulp.

One thing I do have to say about Ilhéus is that it looks like no wire ever attached to a pole has ever been removed. Wires dangling from poles and snaking up the sides of building are almost everywhere you look (as you can see in the photo of the Bataclan), making it discouragingly difficult to get clean shots.

About the Bataclan (in Portuguese). Not to be confused with the Bataclan Theater in Paris.

One thing I do have to say is that they have a lot of fun with trash bins in Ilhéus. Here is one shaped like a cacau pod and I saw one designed to look like a tennis ball at a beach tennis club’s courts. As near as I can figure out, beach tennis is sorta kinda like badminton.

During the Festival

Taken just minutes after the official opening on Thursday evening in the outdoor tent. At times, this area was uncomfortably crowded, especially because very few people were wearing masks. I have to say it felt really weird to me to be in crowded spaces where few were masking.

Taken late in the afternoon on the final day – busy but not crushingly so.

In the end, one festival looks tends to like like every other festival. There are stands and there are people and the people want to learn about what is being offered in each stand. In that respect, Chocolat Bahia is no different from Chocolat Xingu in Altamira, where I was just ten days previously.

What is/was different is who/what is occupying the stands; their product offerings and their stories. And sometimes my story.

[L] Temporary jagua (the dye is made from jenipapo) tribal tattoo; [C] Jar of crystallized cupuaçu; [R] Tree to Girl chocolates by Ju Arleo.

I missed getting a temporary tribal tattoo in Altamira so I was quick to jump on the opportunity to get one in Ilhéus. Unfortunately, it was so warm my arm was moist and so the dye did not set properly and the design quickly took on an unanticipated watercolor look. (I’ve been thinking about getting a second tattoo and if I go to Belém in September I will look for someone there to give me a design similar to this one in a similar location, in solid black. I like the way this looked on my arm.)

After fresh jabuticaba, my favorite fruit is cupuaçu in any and every form. On the last day I purchased every single remaining piece from an indigenous women’s cooperative (photo below). It is so good it’s all I can do not to eat it all in one go. Right now I am having cravings ... the remaining pieces in a container on the fridge are thrumming a siren “Eat Me!” call. (Is it just in my mind? Am I just imagining I can smell it?)

[L] Dinner Friday night; [C] Everyone knew all the songs (except for me); [R] A display of replica ceramic cocoa pods from Cores da Terra.

Rob Willemsen, the colleague with whom I was giving a talk on the global markets for cacau fino, is originally Dutch and has been working in cacau in Brazil for years. We were on the same flight from São Paulo to Ilhéus and staying in the same hotel. We took a cab from the airport to the hotel and along the way he started talking about acarajé; had I had it before, and, if not, that I could not leave Bahia without tasting it.

In the food court in the tent (which also was offering up some amazing locally-brewed beers), I got my chance to taste acarajé, along with abara, vatapá, camarão, and salad. Acarajé and abara and made from a similar dough whose main ingredient is a paste of beans, typically cow peas or black eye beans. Acarajé dough is drier and is fried in dendé (red palm oil). Abara dough is wetter and is formed and steamed in leaves, kind of like a tamale without any filling.

Vatapá is made from a fish broth (which may or may not include shrimps) into which finely-ground bread crumbs are added, stirring to form a lump-free thick paste.

The food court was in this tent where a stage was set up and bands played more or less continuously from 5pm to closing at 10. I did not recognize a single piece, but it seemed to me that everyone else not only knew every song but knew the lyrics to every song. Much food was consumed, beers were drunk, dancing was done, and fun was had all around.

Rounding out the photos above is a display of fine ceramics from Cores da Terra. In addition to huge displays of ceramic replica cacau pods of many varietals, there are more traditional items through people-sized sculptures. Fabulous work. I brought some back with me in 2017; unfortunately I knew I was going to be pressed for weight allowance in my luggage so I did not bring any back this time.

Fazenda Bonança

In 2017 I had the opportunity to visit the Mestiço workshop in São Paulo, helmed by Rogério Kamei and Claudia Gambia. Other workshops I visited on that trip included Baianí, Luisa Abram, Mission Chocolate, and CHoKolaH. This would be my first trip to a farm owned by one of these makers – Mestiço. (Mission Chocolate uses their beans as well.) The adventure began early Friday morning, headed in the direction of Itacaré.

A milestone sign on the way to Fazenda Bonança – burro crossing.

Fazenda Bonança has been in the Kamei family for more than 50 years. While at the moment there are more than twenty families working and living on the farm, at its peak production it had at least three times that many. Amenities include a school building and a fiber-optic Internet connection.

Fazenda Bonança is definitely a working farm.

One of several drying pads/solar dryers on the farm. We were able to stay ahead of rain most of the day, we got caught out walking back from the farm.

While at Fazenda Bonança, I learned of an approach to fermenting cacao I had never heard of. It has been used in coffee – “sprouting” – for some time, but experimentation had only recently begun in cacau in Brazil. (To be fair, there is a patent application for a variation of this approach by a big chocolate company, but that patent appears to describe a lab-scale method not suitable for production.)

Simplistically, sprouting is a 100% anaerobic fermentation that takes place in a light-proof container over the course of 12-15 days. While this is much longer than conventional fermentation, once the seeds are in the fermentation vessel and the airlock (to allow for the release of CO2) is installed, absolutely no work needs to be done. Another aspect of the process is that the temperature in the fermentation vessel never reaches 40ºC making this a truly raw fermentation (for those who care).

There is another intriguing aspect in that this approach appears to be a lot like sous vide cooking – there does not appear to be much risk of over-fermenting if the beans are left for longer than the 12-15 days.

While all the fermentation vessels I saw in use were 200L, there is no reason why this approach could not be used for microferments down to 1kg in the right vessel. There is one process in getting the beans ready for fermentation, which is to remove much of the juice (not the pulp), which can be done in a mechanical juice press, not a despulpador.

The photo of the mass of beans in the center was taken less than an hour after the fermented beans were spread onto the drying table in one of the tented solar dryers. As you can see on the right, the (Catongo – an albino Forastero) bean looks like it has been washed – and this is with the skin still on! The skin will oxidize and turn brown during drying.

One main benefit of the technique is that it produces beans with no acidity, bitterness, or astringency. While this may be good outcome for some varieties, experiments are underway with flavor varieties to determine if it produces beans that can make chocolate that is as good as, or better than, conventional fermentation techniques.

One other side-effect of this process is that the beans are EZ-Peel. At ambient temps the skins of the roasted beans are very easily removed. Not at 100% efficiency, but much higher than trying to peel conventionally fermented, dried, and roasted beans.

This Way to The Cabruca!

[L] Cabruca that is very open; [C] Rogério and the Bonança mother tree; [R] The FB nursery.

Cabruca is a form of planting that respects biodiversity that is fairly common in Bahia. One distinguishing characteristic is that the cacao trees are not planted in neat, even rows, and there tends to be a much higher percentage of shade than is typical. The cabruca in this part of the Fazenda Bonança farm is quite open and is partly the result of not replanting fallen shade trees over mature trees. Cacao yields under cabruca can be as low as 300 kg/ha, making it less profitable (or not profitable at all) when compared with other planting methods. However, because of the desire to no further harm the biodiversity of the second-largest rainforest in South America – the Mata Atlântica – cabruca farming is enthusiastically embraced by many for its many environmental benefits.

There is a variety that was developed on the farm named Bonança, and Rogério is standing in front of the mother tree in the middle photo. Material for grafting is taken from this tree. The nursery at FB is capable of producing up to 20,000 seedlings (all grafted) of mixed varieties – Bonança, BN 34, some EETs, parazinha (Amelonado Forasteros), and more – per year.

Before and After: One of my favorite activities – tasting the pulp of many different varieties of cacao one right after another. [L] The yellow pods in the lower right are the parazinhas.

Fazenda Capela Velha

Capela Velha translates to Old Chapel, and it is a working farm that is also a popular tourism destination located along BA 262, (known as the Estrada do Chocolate) on the way to Itacaré.

A group of us Ubered from our hotel along the north beaches to one along the southern beaches where we joined the press group for the trip. We arrived early, so after a coffee (better than that served in our hotel) with colleague Ron Willemsen, I wandered off to renew my acquaintance with the beach.

I like the formal tension in the arrangement of the two trees on the right with respect to each other and to the edges of the frame in this scene. A pleasing bonus on top of the salt smell and crashing sound of the waves.

[L] Not the nicest weather day; [C] Carlos Tomich, one of the owners of FCV, is the pioneer in exploring the use of “sprouting” fermentation process in Brazil; [R] A short tasting before the walking tour also gives visitors a chance to purchase merch.

I described a little bit about sprouting fermentation above, and the right two images show a little more detail about some of the setup employed at FCV. The 200L blue barrels are opaque and oxygen impervious. Beans, after having some of their juice removed (which is not wasted and is used in the tasting room and for other products) are added to the barrels until they are full. Once the barrel is locked tight and the airlock (which allows the gases that develop during fermentation to escape without allowing oxygen or bugs to enter the barrel) is installed, the barrels are left completely alone until fermentation is complete – a process that takes from 12-15 days.

The result is beans that, when dried, have very low levels of acidity, bitterness, and astringency. There is a chocolate factory on site and beans fermented using this process are converted into chocolate bars. I purchased four (below, left) and will be offering up my thoughts on them (and other bars I purchased while in Bahia) in the coming weeks.

I am not sure of the variety of the beans in the two other pictures, but I was gifted with a kilo. One thing I noticed while at FCV was that the beans were very easy to peel. While my success rate in getting whole beans was not 100% it was higher than with any other bean I had ever tried – except ones straight out of a roaster when peeling them courted second-degree burns. One thing this leads me to suspect is that these beans are also going to be very easy to winnow completely clean.

If you’re interested in getting a sample of these beans I am working on securing a large sample that I can break down and share. Let me know and I will put you on the list.

Chocolat e Muito Mais

Many people might look at the fact that beans from other countries cannot legally be imported except under very narrow circumstances (Brazil is a net importer and the beans that are imported are commodity/bulk) and from just one country – Ghana – because of the fear of the introduction of another cacau disease that could have the same effect as the introduction of witches broom in the 1980s as a hindrance to creativity.

From a chocolate-making perspective, however, Brazilian craft chocolate makers get to rely on the fact that there is an enormous amount of diversity in the cacau that grows in their country. Some of the varieties have been introduced from other countries, some are locally-bred hybrids, but many are native, and this includes a wide selection of wild varieties.

One of the other things I mentioned in one of my presentations is that between Pará and Ilhéus I had noticed that the overall quality of the chocolate being produced by local makers has improved considerably since my first visit in 2017, and noticeably since my visit in 2020.

Another thing I mentioned during one of my presentations at the festival, one of the things that impresses me most about the Brazilian specialty/craft/bean-to-bar chocolate industry is their creativity with flavors.

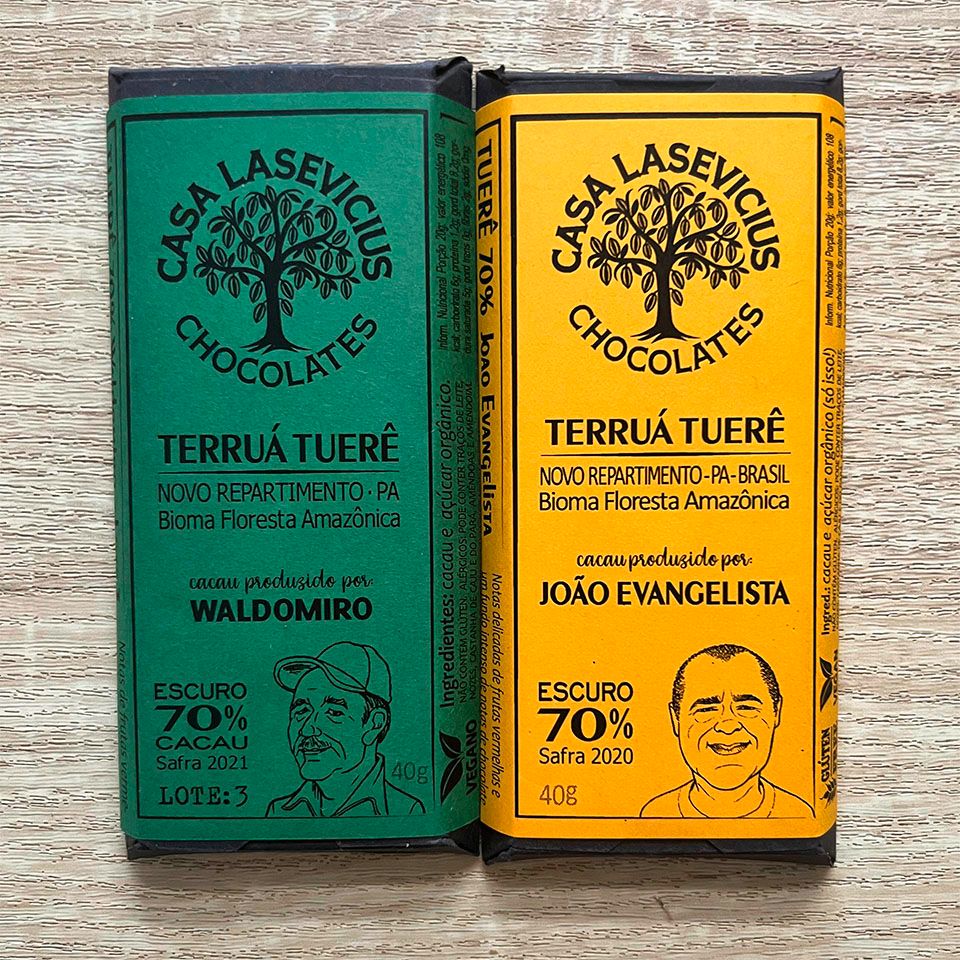

[L] A selection of seven bars using award-winning beans from the Brazilian Cocoa Awards; [C] A selection of two bars made from wild beans from the Terruá Terrê project in Pará state; [R]; A selection of flavored bars and bars with inclusions. All from one maker: São Paul-based maker Casa Lasevicius.

I want you to pause a moment and consider that the above fifteen bars are from one maker, and that nine of them highlight different cacaus – all from Brazil. That maker is the iconoclastic Bruno Lasevicius, the current president of the Associacão Bean-to-Bar Brasil, which counts more than 50 members. In all Bruno, these days Bruno works with as many as fifty different beans each year from all over Brazil, sometimes in quantities that are less than a full bag. While there are some I definitely prefer over others, they are all very well made and on their own demonstrate the vast potential that is Brazilian cacau.

Brazil is a net importer of cocoa, but it does export, and ICCO has declared that 100% of exports can be classified as cacau fino. However, total exports in 2021 were less than 650MT to all customers globally, with a significant percentage making their way to Japan, reportedly.

TOP row: [L] Bean-to-Girl bars from Ju Arleo; [C] A mixed bar (flavored white and dark chocolates in the same mold cavity); [R] An assortment of bars from other makers at Chocolat Bahia. BOTTOM row: [L] An assortment of bars picked up in Bahia and São Paulo.

My interactions with young (she was at the time I met her a week shy of her tenth birthday) Ju Arleo are the most special and inspirational moments I had at the festival. While the Arleo family has long been growing cacau, tw0 years or so ago young Juliana was convinced to start making chocolate – and convinced family members, too. Today they are making eight different varieties of what they call Bean-to-Girl chocolate, with young Ju out front representing the brand. And I found her to be a great brand advocate – better in some respects than other makers three to five times or more her age. With young people like Ju – with the support of her family, of course, and which can not be overstated – the future of Brazilian craft chocolate is in good hands – especially if she can learn from the generation that has preceded her.

Benevides was not in business when I was in Bahia in 2017, but was in 2020 when I first encountered the name in São Paulo. In 2020 they are having fun experimenting with flavors and formats commercially. This bar consists of two parts – a white chocolate that is flavored with cinnamon, and a dark chocolate that is flavored with coffee beans. The bar is deposited in such a way that most bites contain both the white and dark chocolate. This concept is something I started playing with about fifteen years ago with what I called then 50/50 bars; my first being a layering of Guittard Orinoco (48% milk) and Nocturne (90% dark). What’s fun here is that two entirely different tasting experiences are present in the same bar, depending on which side is up (experienced first in the nose) or down (experienced first on the tongue). Demonstrating this effect to the head chocolate maker, talking through the process and experiencing it with her, was a blast, and we got into a long discussion about how this effect might be used in conjunction with other flavor combinations.

The photo on the (top) right shows five bars from five different makers that I purchased or were gifted at the show – and this is on top of the bars I picked up in Pará. Clearly, I have my work cut out for me over the next couple of weeks as I work through my bounty, struggling to keep the chocolate from melting in the NYC summer heat.

The photo on the (bottom) left shows another assortment of bars. The first five are from makers based in SP using a variety of Paraense and Baiano cacaus, with the bar from Mission including another endemic Brazilian nut – castanha de baru. When shopping in SP on my return I saw a bag of these nuts and snapped one up to familiarize myself with it before tasting the bar. They’re fabulous.

The photo on the (bottom) right shows two examples of quebra quebra (literally ‘break break’) barks from Dengo. Those who have been following me for a long time know that I am a staunch advocate for what I call “bean-to-bark” products – chocolates that are slabbed rather than deposited and molded that contain inclusions and toppings. You will notice a similarity between Dengo’s quebra quebra and Läderach’s FrischSchoggi™. They are similar in some respects (the main differences, to me, are that FrischSchoggi incorporate traditional European/Swiss flavor attitudes and Dengo’s don’t) and they are merchandised at retail in the same ways, in stacks that can be purchased by weight in a pick-and-mix fashion. If you’re a craft chocolate maker and you’re not doing this – in my opinion you need to be, even if you don’t operate your own retail shop.

On top of that is all the incredible diversity of fruits (including cupuaçu, jabuticaba), nuts (fresh castanha do pará (Brazil nuts) are so much better than what can be found in most products sold in the US), and other ingredients that come from the Amazon and the Mata Atlântica. And that’s before we factor in culinary influences from a wide variety of cultures.

[L] Cupuaçu; [R] Dried, processed, cacau leaves

As I have mentioned elsewhere, cupuaçu is one of my favorite fruits and there was no lack of products using the pulp in one way or another. One of my favorites, shown above, was in a soft dehydrated form – chewy and delicious. Addictive, too. On Sunday afternoon, the last day of the festival, I bought all I could find ... and it’s already all eaten, less than two weeks on.

I saw dried, processed cacau leaves being used for packaging in a variety of ways, including as outer wrappers for chocolate bars and in decorative lamps. The leaves are surprisingly supple and the processing steps eliminate most surface contaminants.

As with the sprouted beans I have developed some supplier contacts in Brazil for people who are interested in getting their hands on them. Prices will be determined, to a large extent, on demand and how they are shipped. I can’t say that the leaves shown are food contact safe (so most of the bars I saw also had an inner barrier wrap), but a quick phytosanitary inspection, which is planned, will let us know what the microbial load is (or isn’t). Again, if you are interested, let me know.

In Closing

Despite the fact that I have spent much of the past week recovering from the compound effects of jet lag and residual fatigue from my bout with COVID, I would do it again in a heartbeat. I know that I will be returning to Brazil in December and I am hoping to return in late-September for the festival in Belém.

Brazil is a huge country and it is impossible to cover its diversity – in cacau, chocolate, food culture, you name it – in just a few short visits. All of my visits are about increasing international visibility for Brazilian cacau and chocolate.

If you’re a chocolate maker and you’ve been hesitant about adding Brazil to your list of origins, it’s way past time to start becoming active on that front. If you want or need sourcing help get in touch with me and I can put you in touch with people on the ground who can help out.

If you have never visited Brazil for cacau and/or chocolate, you should consider it. There are chocolate festivals all over the country in many different states, and each offers a different view into cacau, chocolate, and food culture. Again, if you’re interested, please let me know and I can introduce you to the festival organizers. (Keep in mind that if you are a US citizen you will need a tourist visa, because the US requires Brazilians to secure visas.)

Finally, if you are a chocolate fan who has never tasted bars made using Brazilian cocoa because you’ve heard it’s not very good, well to quote the estimable Bob Dylan, “The times, they are a changin’.” While much of the more easily available bars are made by makers outside Brazil (including Heinde & Verre, Zotter, and Dick Taylor), there are excellent bars that are being exported that are worth seeking out from makers that include Luisa Abram, Bainí, and Mission Chocolate, among a few others.

Brazil is also at the forefront of some interesting experiments in fermentation, including the aforementioned “sprouting” process as well as “Anima” fermentation from Bertus Eskus, who is the innovator behind TropMix (what Valrhona calls double-fermented), and a founder of the Cocoa of Excellence program. Keep watching both of those techniques as they are destined to become more well kn0wn.

Finally, if there is just one prediction I can confidently make about Brazilian cacau and chocolate over the next five years, it is that it will burst forth on the international scene as a hugely desirable origin given its quality, diversity, and sheer joie de vivre – the exuberant enjoyment of life, which, to me, is the best single descriptor of Brazilian cacau and chocolate culture.

Or maybe we should say alegria de viver ... because the Portuguese is more on point than French.

Leave them in the comments.