Birth of an Industry: Chocolate in New York City, 1900-1930

The global chocolate boom of the late 1800s reached its peak by 1915. In its wake a new type of industry was born, amid a race to compete at an ever-growing scale.

New York’s prominent makers enjoyed extended prosperity, but the foundations built in the ‘Golden Age’ started showing cracks as the Roaring ‘20s gave way to the Depression.

By 1900 the New York City grid had filled in, and bound by natural borders, real estate began to go vertical. The first skyscrapers darted upward, giving shape to the skyline. The boroughs expanded, too, after the Brooklyn Bridge was built (quickly followed by the Williamsburg, Manhattan, and Queensboro). Planning was underway for the network of underground subway tunnels that would soon replace the streetcars and elevated trains. With continued immigration and urbanization, the population swelled to 1.5 million dwellers.

Author Luc Sante once referred to the city as an “unfinished project,” echoing the notion that, “New York is a city that will be replaced by another city,” put forth by architect Rem Koolhaus in his 1978 classic, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. The constant regeneration suppresses a connection to the past, or perhaps the flux distorts our perception of it. Sante notes in his book, Low Life, that generational nostalgia is cyclical, and inevitable. New Yorkers have a tendency to look back fondly at ‘simpler times,’ or pine for the ‘good old days.’ Much like the jaded hipster of today, New Yorkers in the 1890s were probably already grumbling that the city had lost some of its charm (or edge).

Much of New York's character is stitched into what is essentially a patchwork collection of settlements and neighborhoods, with fluid borders that expand and contract, remapped by assimilation and gentrification. Immigrant communities lingered in tenements and storefronts for a generation or two before dispersing, leaving only traces behind. Bustling business and manufacturing districts stood for decades, too, bulldozed by the march of progress. Some still exist as shells of their former selves, like the Meatpacking, Garment, and Flower districts. Nothing remains of lower Manhattan’s Washington Market, the vibrant commercial center for food and produce of all kinds, anchored by the processors, importers, and warehouses in Tribeca. Dismantled in the 1960s and moved to Hunt’s Point in the Bronx, what was once the city’s pantry was paved over to make way for construction of the World Trade Center complex.

Cocoa Corners

According to the March 29th edition of The Sun in 1904, “folks living in apartments within a block of a certain big East Side chocolate and confectionery factory,” came to view their proximity as a mixed blessing. It’s possible the factory in question was the East 22nd Street operation run by Claude Crave and Evariste Martin (and Henry McCobb before them). “The aroma from the factory pervades the whole neighborhood. To the occasional passerby it is delightfully fragrant, but after living near there and sniffing it every day the tenant soon cuts chocolate out of the list of things he wants to eat or drink.”

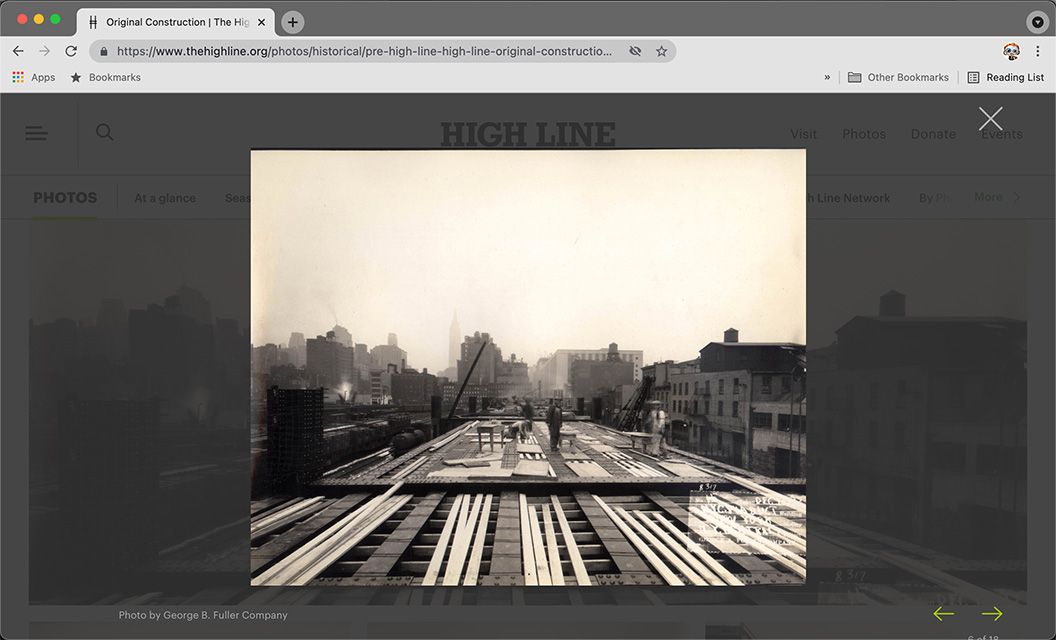

From the early 19th century, New York’s chocolate makers were loosely concentrated by neighborhood, from the East River waterfront, up into the Lower East Side, and over to Tribeca and SoHo. I’ve seen a few passing references to ‘Cocoa Corners’ designating, perhaps, a particular neighborhood, or the city itself as an important locus of the chocolate industry. If one such cluster of factories was worthy of the title, it might be the stretch of 10th Avenue around 30th and 31st Streets. For a time, the manufacturers Runkel Brothers, Knickerbocker, Poyet, and Hess Brothers all occupied this area, where the tracks of the New York Central Railroad turned toward 11th Avenue. The grade-level railroad – dubbed ‘Death Avenue’ for the number of pedestrians struck by trains – was eventually elevated and is today an urban park known as the High Line.

The image linked to below shows the construction of the elevated rail line in the early 1930s, looking east on West 30th Street, toward the Runkel factory at 10th Avenue, and the silhouette of the recently built Empire State Building further behind.

The New York Times on January 9th, 1927, memorialized the neighborhood with:

“What is perhaps the sweetest and most intriguing scent in all the city is that which permeates West Thirty First Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, where factories devoted to the delectable occupation of manufacturing chocolate bars, with almonds and without, are situated. The chocolate aroma did not win its place without struggle for the engines that haul and shunt freight cars on Tenth Avenue give off a gassy, sooty smell that makes an acrid plea for recognition.”

By 1910 another chocolate making district arose in the old Wallabout neighborhood of Brooklyn near the Navy Yard, today in the shadow of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway as it winds its way from Williamsburg into Dumbo. Bischoff, Rockwood, and Wallace had all moved into the neighborhood from Manhattan by the early 1900s. Greenfield, established in Manhattan in the 1850s, set up a factory on Lorimer Street in nearby South Williamsburg. Newer companies popped up, too, including Atkinson on Bedford Street and Pirika on Dean Street further south in Crown Heights. The completion of the Queensboro Bridge in 1909 also spurred development in Long Island City into the 1920s; Maillard built a new factory near the Sunnyside Yards, and Loft relocated to Vernon Boulevard from its original SoHo facility at Broome and Centre Streets.

New York City’s busy chocolate neighborhoods are not that far removed from living memory, yet the tangible remnants are few. The smells that filled the streets are, of course, long gone. The handful of old factory buildings still standing, once processing mountains of cacao beans, have been carved up into loft-style apartments, offices, and retail stores.

Consumer Trends

A host of factors fueled the chocolate boom as it entered the 20th century, influencing both the consumer experience and the types of new chocolate products flooding the market.

- Chocolate and cocoa had become household pantry staples, used to prepare beverages and desserts. Increasingly accessible in price, grocery shelves stocked multiple regional and national brands.

- Chocolate packaged in larger ½- and 1-pound quantities for cooking were supplemented by smaller 5- and 10-cent snacking bars. ‘Plain’ sweet dark and milk chocolate bars led the way for varieties with simple inclusions like nuts and fruits.

- Beyond the grocer, two additional pipelines split the flow of chocolate: fine bonbons could be found in branded boutiques and upscale department stores, while smaller retailers sold cheap candies to anyone with a penny to spend.

- Beginning in the late 19th century newspaper and magazines printed recipe and lifestyle content with greater frequency, and chocolate manufacturers began publishing their own promotional recipe books.

- Chocolate companies invested heavily in marketing and brand image as the era of ‘Madison Avenue’ advertising emerged by the 1920s.

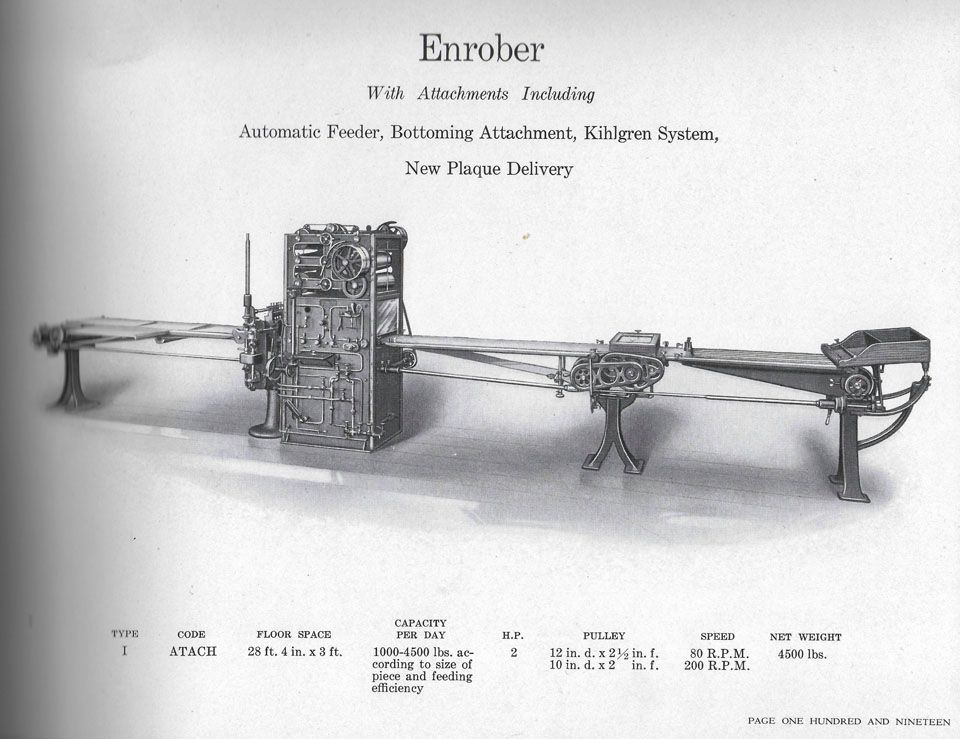

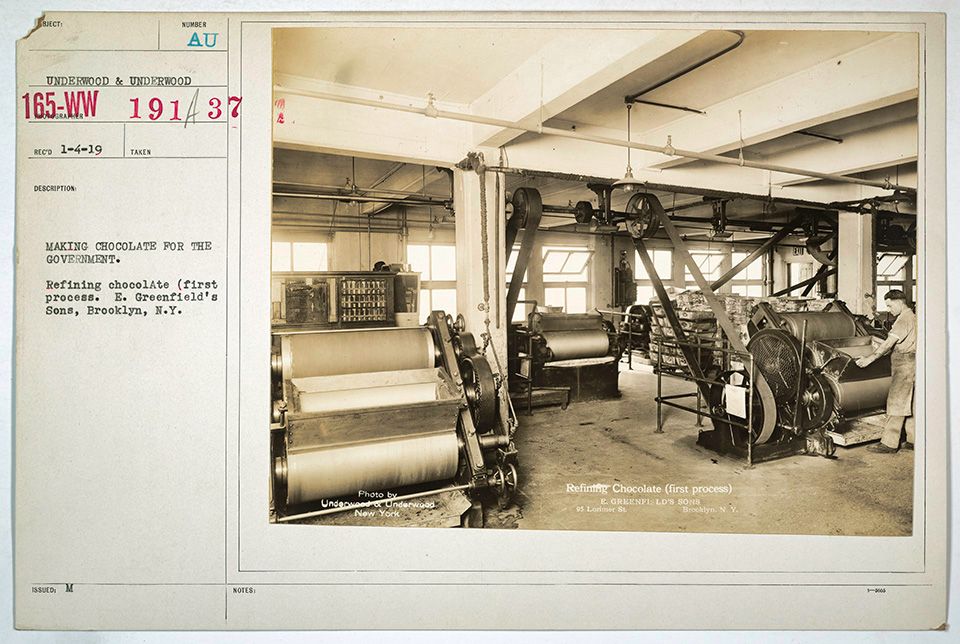

- Chocolate making machinery got bigger and faster in the early 20th century; greater throughput boosted a factory’s potential capacity to several tons per day. Roller refiners were installed alongside older stone grinding technology, resulting in finer, more consistent products.

- Development of the enrober, attributed to French machine maker Savy around 1903, replaced skilled hand dippers and paved the way for more sophisticated, mass-produced bonbons and candy bars.

- Perhaps driven in part by marketing, by the early 1900s chocolates and candies had become tightly woven into holiday traditions, like Christmas and Valentine’s Day (and the Loft company was making chocolate ‘gelt’ coins for Hanukah in the 1920s).

- Though health and wellness played a smaller role in chocolate marketing by the 1900s, chocolate consumption was loosely tied to the moral inclinations of the temperance movement. The crusade against alcohol grew in popularity in the latter half of the 19th century, culminating in the passing of the 18th amendment in 1919 and a decade of Prohibition.

State of the Industry

The confectionery trade journals that survive from the first decades of the 20th century offer a fascinating glimpse of the industry at a time of rapid growth. Within the flip of a few pages, one finds the latest in product lines, machinery, and supply chain news. One also gains insight into the range of wholesale chocolate buyers being marketed to – the grocers, soda fountains, ice cream manufacturers, and retail confectioners. We see the wares of the satellite ingredient and supply trades, the cocoa bean and butter brokers, and the rise of the flavor houses that drive product development today. As the 1900s progress, what becomes overwhelmingly evident is the trend toward fewer chocolate manufacturers producing larger volumes. They supplied a growing hunger for chocolate bars in the retail market, but also funneled base products and ‘coatings’ into a secondary manufacturing market of candies, syrups, and baked goods.

In an article written for The International Confectioner in April 1914, T.B. McRobert lays out the simple economic realities and high barriers of entry segmenting the industry and further fueling the growth of larger firms:

”The chocolate trade indeed is now more or less suffering from what might be called illegitimate competition. The day is long past in this country when anyone with small capital and a few antiquated machines can start into the chocolate manufacturing business with any hope of success. It has become a business needing large capital, perfect equipment, and selling ability to find a market for products, since profits are to be found not in lower percentage on sales but small profits on a large business.”

“The writer has been connected with the cocoa and chocolate trade for many years and can say as a matter of knowledge, knowing material costs, labor costs, and overhead charges, as well as the costs of selling, in the case of the cheaper grades of coating, selling cost today is little or no more than a small brokerage. I say that no coating user can make an actual saving by making his own coatings in place of buying them.”

“It is to be considered also that the big chocolate maker has a market for every part and sorts of cocoa beans. What would not do for coatings, or powder, can be turned into ‘Penny Goods’ and sold in large volume, but to produce this class of goods a considerable outlay is required, especially in moulds. This class of goods the average good confectioner would hardly care to make, and if he did so might find it hard to find a market for them.”

“The writer knows of a number of manufacturing confectioners who have started to, and for a while did, produce their own coatings and finally gave it up. They told me that they found that they could not produce a satisfactory coating for their fine lines and could not save anything on cheap coatings. Cheap coatings are and always have been sold exceedingly close to cost by the big chocolate houses... Asked how large a user a buyer should be before attempting to make their own coatings, I should say, at least, 3,000 lbs. per day and this production would not be much more than 10% of the amount of coating produced by any one of the leading chocolate houses in this country.”

“Then, too, granted that all needed machinery has been bought and installed, there yet remains what may be called the ‘Human Equation,’ in other words the ‘knowing how.’ Really high-class men, men who know cocoa from the bean up to finished goods, are rare birds...”

McRoberts continues with a thorough cost-benefit analysis on the production of chocolate and cocoa, and the conclusion is obvious to those of us familiar with chocolate production today: chocolate as an industrialized product inevitably put the power and profits into the hands of the few who were able to compete at economies of scale. Also implied by McRobert is that at volume, high quality or “fine lines” of chocolate were in danger of being choked out by a market flooded with cheap, low quality products .

A few of New York’s chocolate making holdovers from the 19th century – now in business for up to fifty years – benefitted from the surge of industrialization, and many new companies sprang up. While an ever-widening variety of 5- and 10-cent candy bars fed a hungry domestic market, the tremors of war abroad would also give a boost to American makers. European production and exports of finished chocolate plummeted during World War I, creating a new opportunity for domestic companies at a global level. Cacao bean trade was also disrupted - consider that many producing origins remained colonies of those very nations at war (British colonies accounted for roughly 40% of global production – Ghana, or the ‘Gold Coast’ was not yet independent) and much of the supply that might otherwise have been destined for Europe ended up in North America.

Annual cacao arrivals into New York City increased from about 1 million bags in 1914 to over 2 million bags in 1917. As the United States entered the war, massive government contracts for cocoa and chocolate rations led to bidding wars and an influx of cash – often reinvested into factory improvements to produce yet larger volumes. A final driver of the continued investment in post-war chocolate and confections manufacturing was the promise of a profitable boom with Prohibition and the banning of alcohol. Existing makers expanded in anticipation of increased candy sales, followed by speculators new to the confectionery business, and even a few brewers and distillers looking to pivot out of necessity.

The shifting market share of chocolate manufacturing in the early 20th century, distributed among fewer and larger companies, was perhaps, at first, a war of attrition. We note the demise of the older chocolate brands in the fine print of bankruptcy filings and unceremonious real estate sales. As company founders retired or died by the early 1900s, we find heirs mismanaging growth, or selling their interests outright. Murmurs of secret strategies to form chocolate cartels and trusts date back to the late 1890s – Walter Baker, Huyler’s, Maillard, and even Menier were among the suspected deal-makers – but universal denials among the concerns quickly quashed the rumors that resurfaced every few years. Some consolidation in the industry was occurring. The Griffing brand was acquired by Crave and Martin in New York City, Baker had absorbed much of its early Boston-area competition by 1900, and in the 1920s Wilbur in Philadelphia purchased Swiss brand Suchard and the Ideal Chocolate Company (itself a merger with Brewster, an old New York maker dating back to the 1870s).

Though the rising tide of chocolate production appeared to lift all ships as they sailed into the 1920s, the turbulence of economic downturn in the 1930s led to more consolidation of those companies unable to weather the storm.

Supply for Growing Demand

As New York was still the primary port of entry for cacao coming into North America during this boom period, one finds some fascinating trends harvested from the data – now far more reliable than the fuzzy figures available for 19th century trade.

- Between 1900 and 1950, worldwide bean production increased six-fold.

- In 1900, roughly 40% of the bean supply was from Venezuela and the Caribbean, and another 20% supplied by Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia, another 20% by Brazil, and only 15% originating in Africa.

- By 1915 Africa would surpass 35% of world production and would hit the 50% mark in the 1940s. Today, of course, Africa accounts for over 70% of world production.

- Those changing numbers are reflected in New York City arrivals between 1914 and 1917, where annual imports of African beans more than tripled over just four years.

- If we zero in on one particular origin and a random year, Trinidad and Tobago and 1916 for example, nearly 167,000 bags or roughly 10,000 tons from that origin were imported into New York harbor alone – the entire production of that country is less than 1,000 tons today, compared to about 24,000 tons exported in 1916.

- Amid the peak of the city’s primacy as a point of entry, of the 351,000 tons of total cacao produced globally in 1916, roughly 26% of those beans (92,000 tons) entered the port of New York. For context, a century later, annual global production now exceeds 4 million tons.

By 1917, with the surge in imports and re-exports, there were calls to form an American trade association out of the need to regulate prices of this increasingly important cacao commodity. In July of that year, The New York Times quotes a trade official, stating the United States, as the, “world’s largest buyer should control prices, not London,” and “the establishment of an American Cacao Exchange in this city would go a long way toward making New York the world’s center for the control and distribution of cacao.”

Founded in 1925, the New York Cocoa Exchange convened in the flatiron-shaped building at the convergence of Beaver, Pearl, and Wall Streets in lower Manhattan until the 1970s. After mergers with exchange boards of other soft commodities coffee and sugar, cocoa is now traded on the InterContinental Exchange (ICE), which states, “futures and options on futures are used by both the domestic and global cocoa and confectionery industries to price and hedge transactions. The ICE Futures U.S. Cocoa contract is the benchmark for world cocoa prices.” Cocoa is also traded on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX). The International Trade Center’s Cocoa: A Guide to Trade Practices describes the impact of the commodity exchanges at the farm gate in simple terms:

“The price paid to the farmer is negotiated individually and depends upon the levels prevailing in the world market. Generally speaking, the futures contracts as quoted in London or New York are taken as the basis for the price, and adjusted for the estimated cost of bringing the cocoa from farm to market.”

The Makers

The landscape begins to shift for New York’s chocolate makers in the early 20th century. Below I revisit the makers profiled in the previous installment of the series and introduce a few others who contributed to the new industrial approach.

Maillard

After founder Henry Maillard died in 1900, the chocolate and confectionery business was directed by his son Henry Marie-François Maillard. The turn of the century was a prosperous period, built on a reputation fostered over fifty years, and the brand enjoyed national recognition. While its 25th street factory would remain for another decade (it included a tea salon that doubled as a chocolate “school”), its flagship boutique and restaurant moved from the Fifth Avenue Hotel after its demolition in 1908 to 35th Street and Fifth Avenue. American gastronome James Beard once noted, “in the ‘twenties in New York, you’d have a good cup of Maillard hot chocolate and a chicken sandwich for 75 cents and you thought you were whirling through the world.” A Chicago shop and restaurant opened on Michigan Avenue in this same period.

Hawley & Hoops

Under Herman Hoops and his family, the company forged ahead after John Hawley’s death in 1913 with improvements to the large factory on Lafayette Street next to the Puck Building. While firms like Maillard and Huyler marketed themselves as luxury brands, Hawley & Hoops embraced the penny candy trade. By the 1920s their chocolate and cocoa processing shared equal billing with gum tablets, licorice, marshmallows, mints, hard candies, and panned items – all sold through candy “jobbers,” the small regional distributors supplying retail stores. In 1913 Hawley & Hoops came under fire after the Food and Drug Administration issued ten violations for adulteration, claiming samples revealed traces of arsenic and shellac. The company pleaded guilty on all counts, and no penalties were imposed save for a $50 fine for misstating the net weight on one of the packages under examination.

Runkel Brothers

Runkel, the anchor of the west-side ‘Cocoa Corners,’ expanded with a Chicago factory in the early 1900s. Founding brother Herman died in 1918, followed by Louis in 1928. The company continued to market both wholesale and retail lines, the latter boosted by the publication of small promotional cookbooks. Never venturing too far into candies, Runkel added to its core line a malt-flavored chocolate syrup under the Runko brand, which sponsored a half-hour radio program on CBS affiliate WOR – a male singing group called the Runko Quartet. Almost 20 years ahead of the modern era of employer-sponsored insurance, Runkel offered a health plan to its workers in 1926.

Huyler’s

The Huyler’s chocolate and candy empire entered the turn of the century with nearly 60 retail stores in 26 cities, overseen by founder John Huyler’s sons. In addition to cocoa products and iconic, pink-wrapped vanilla chocolate, their boxed bonbons were pitched as the standard in thoughtful gifting. Their taglines included, “A token of good taste”, and, “A man is known by the candies he sends… Of course, it’s Huyler’s that she wants.” Advertisements depicting women in the latest flapper styles emphasized the unboxing experience with, “…smartly fashioned packages that appeal to la femme du beau monde.”

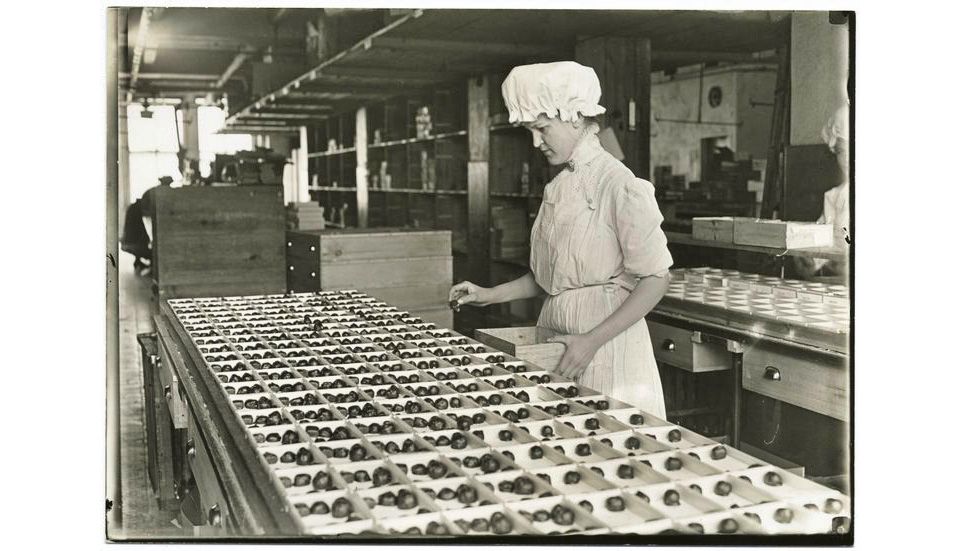

Into the 1920s the Irving Street factory posted near daily ‘help wanted’ notices in New York newspapers. seeking young women and girls for finishing and packaging, adding “experience unnecessary; steady work; good pay; cafeteria on premises; free medical service; uniforms supplied.” With retail stores and additional small branch factories established throughout the Northeast and Midwest, Huyler’s also offered its own delivery service.

The Huyler heirs decided to cash out in 1925, selling the brand to a banking syndicate for a rumored sum of $7.5 million (over $100 million today). The company was quickly turned over to retail magnate David Schulte, who assumed a controlling interest in 1927. Signaling a shift in priorities, he sold the Irving Street factory John Huyler built back in 1883 (three new apartment buildings were planned for the site in 1928).

Schulte gradually abandoned manufacturing to focus more resources to the restaurant chain, of which he envisioned 500 units nationwide Those optimistic goals were dashed with the onset of the Great Depression. The brand limped through the next two decades, and despite failed efforts to revive the business in the early 1950s, the national brand once identified with elegance was a shadow of its former self, by that time already remembered with wistful nostalgia.

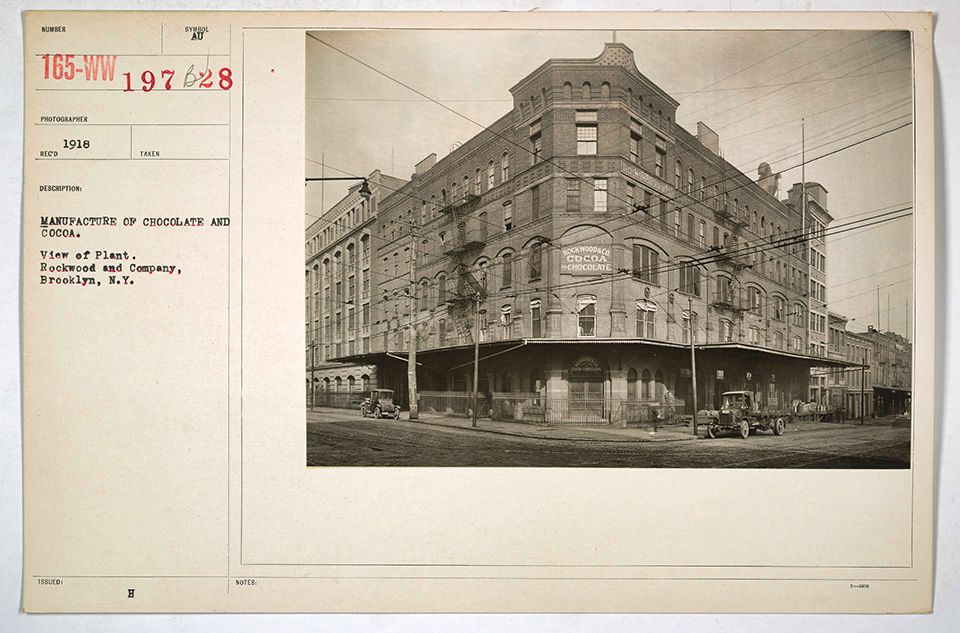

Rockwood Chocolate Company

Wallace T. Jones moved his company from Manhattan’s Cherry Street to Washington and Park Avenues in Brooklyn by 1904. Rockwood maintained its volume wholesale business, while also producing retail chocolate bars with nut and fruit inclusions. Perhaps in response to the development of Wilbur’s ‘buds’, in 1915 Rockwood promoted a line of wholesale chocolate, likely deposited into small drops or pistoles, calling it the, “New Rockwood Method of preparing your coating from Rockwood & Company’s Chocolate Dewdrops,” for, “users of coatings who are interested enough in saving time, money, and labor.” Jones’ sons Pierre and Wallace Jr. joined the company in 1918.

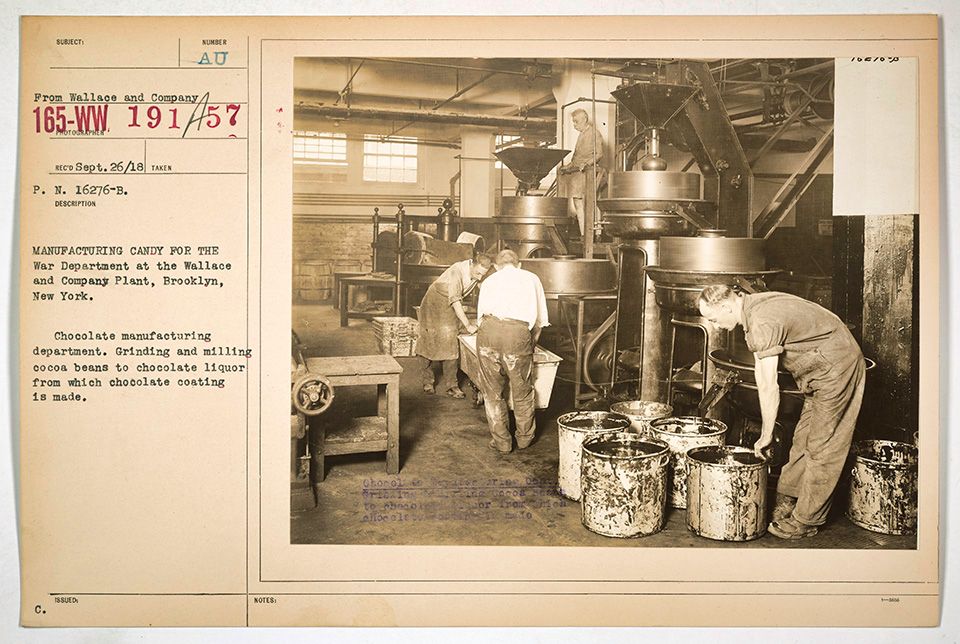

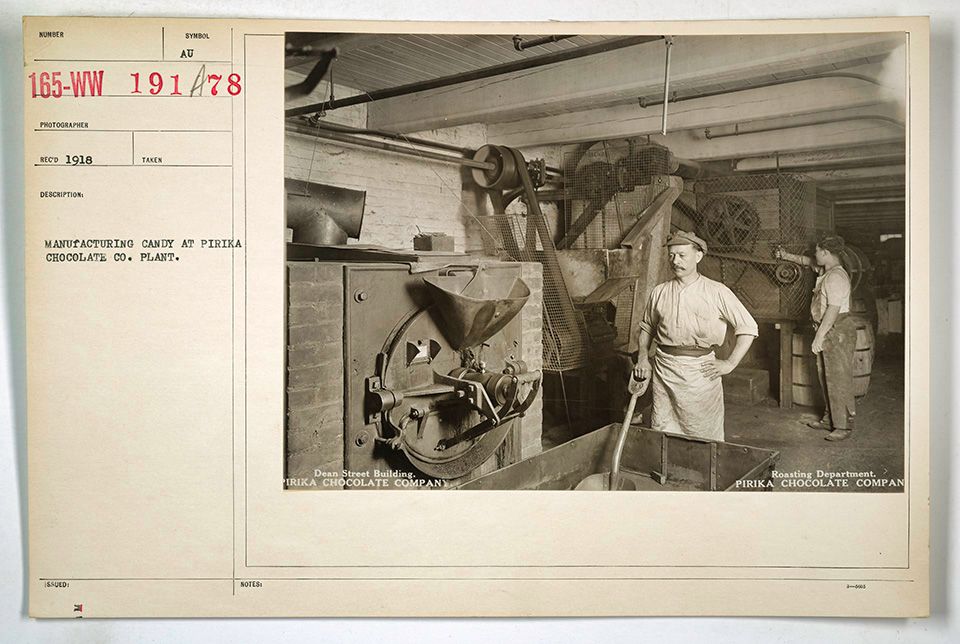

It was also during this period that production for the war effort was in full swing. The Rockwood factory and those of three other Brooklyn companies (Wallace, Greenfield, and Pirika) were subjects of a photojournalism project grouped under the titles Industries of War, or Making Chocolate for the Government. The dozens of images now accessible through the National Archives serve as a useful tool in understanding the factory layouts, the machinery used, and the working conditions of these early 20th century factories.

In May of 1919, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle headlined an article with, “Gutters Run Fudge; Urchins Run Miles to Chocolate Fire; River of Molten Candy Blocks Sewers – Floods Streets as Rockwood Factory Burns.” Focusing on the commotion caused by the children among the onlookers, the piece adds, “Little fellows fell on their knees before the oncoming flood and dipped it up greedily with their grimy fingers… Here ended the episode that will go down in the anthology of Fudge River as the greatest little fire that ever occurred in Brooklyn.”

Wallace T. Jones died in 1922 at the age of 70. His sons would carry the mantle at a time when Rockwood’s productivity was still on the rise. One of several innovations to emerge from the firm through the 1940s was Wallace Jr.’s 1934 patent for an early version of a continuous conching machine, “which is capable of controlling the flow of the chocolate and at the same time ensuring the thorough treatment of each portion before it leaves the machine.”

Rockwood would become not only the largest maker in New York City, but for a time was also the second largest chocolate manufacturer in the country behind Hershey.

Ernest Greenfield

Ernest Greenfield, among New York’s first wave of European immigrant confectioners, arrived from Strasbourg in 1848. By the 1850s he set up shop on Barclay Street at West Broadway, at the edge of the Washington Market district. Greenfield was one of the confectioners who also just happened to manufacture his own chocolate, though that production would increase in the decades that followed. Observers looking back at Ernest’s career in the mid-19th century credit him for sparking a shift toward more modern means of production, as well as advancing packaging from simple bags to fancy boxes. Sons Nelson and Joseph joined Ernest’s company in the 1870s.

Perhaps the worst of the many fires suffered by New York’s chocolate makers, an explosion at Greenfield's 63 Barclay Street factory in December 1877 killed at least two passerby on the street, injured dozens, and severely damaged three neighboring properties. The suspected cause was the ignition of fine, highly flammable starch dust, ever-present in candy factories that used starch-molding techniques to form bonbon centers.

Ernest retired in the 1880s and died soon after. A new modern factory was established in Williamsburg, Brooklyn by the 1890s. In the early 1900s, Greenfield produced dozens of trade postcards, many depicting cityscapes and landmarks of Manhattan. They also produced a set of early baseball cards, which are extremely rare collectibles today. By 1915, both of Ernest’s sons had died. The factory expanded once again to Lorimer Street near Marcy Avenue, the location documented in the Industries of War series in 1918. Greenfield’s chocolate candies remained popular throughout the 1920s. By 1937, the business had dissolved, its six-story factory building sold.

William Wallace

Born in Virginia in the late 1820s, we find William Wallace’s confectionery shop at 29 Cortlandt Street by 1870. It was a prime location with plenty of foot traffic to and from the Hudson River ferry terminal and nearby Washington Market. His factory store became well-known for its elaborate window displays. Like Greenfield just a few blocks away, Wallace grew his candy business to include chocolate making over time. John Hawley was an employee at Wallace & Company before staring his own venture on Chambers Street in the mid-1870s.

In the 1890s, Wallace maintained its original retail location while expanding into a new factory space at 160 Monroe Street on the Lower East Side. It’s unclear when William died, but sometime in the first decade of the 1900s the company moved again to Park and Washington Avenues in Brooklyn, right next to the Rockwood factory.

After the 1920s, the Wallace trail goes cold – sort of – though we still see Wallace branded chocolate assortments advertised throughout the country into the 1950s. Unknown are what, if any, ties to the original company and the Brookl6n factory remained.

Frederick Bischoff

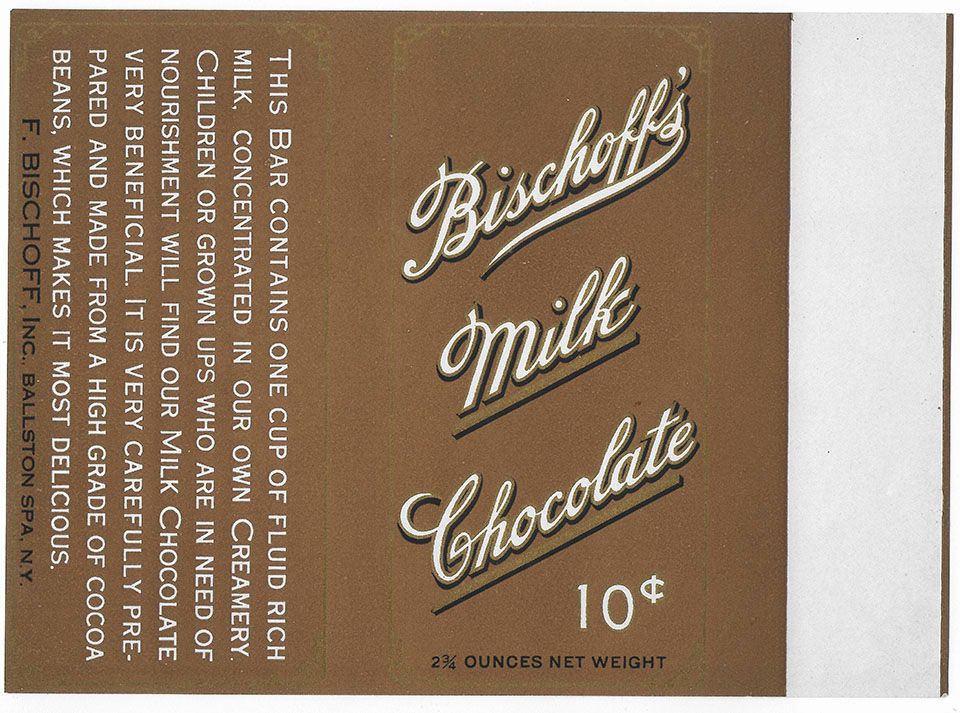

Arriving from Germany in 1873, Frederick Bischoff found his way into chocolate manufacturing by way of the homeopathic pharmacy he ran on Worth Street near Mulberry, in the old Five Points neighborhood. He took over an existing chocolate factory on West 29th Street in 1893 and produced cocoa that he claimed was, “very soluble, easily digested, and admirably adapted for invalids" and that it could be purchased at "Homeopathic Pharmacies in general."

Within two years Bischoff had expanded his chocolate making ambitions with a factory in the Gowanus neighborhood in Brooklyn (and by that time had dropped any references to health). In the early 1900s the Bischoff factory moved to Wallabout – first to Ashland Place and then to Sands Street alongside the Manhattan Bridge. A specialty of the brand was its large 25-pound blocks of chocolate put on display in ‘five and dime’ stores; a clerk would use an ice pick to break off chunks of chocolate, sold by weight.

A 1909 meeting of the Executive Committee of the Association of Chocolate Manufacturers at the Hotel Waldorf was a ‘who’s-who’ of the reigning chocolate cognoscenti – Louis Runkel, Milton Hershey, Herman Hoops, Wallace T. Jones, Isaac Edesheimer of Huyler’s, and Frederick Bischoff, among others. Enjoying the brisk business shared by other factories in the neighborhood, The Simmons Spice Mill in August 1917, noted, “Among the chocolate manufacturers who find business booming at present is F. Bischoff, of Brooklyn. Considerable new machinery has been contracted for, including four No. 5 Burns roasters.” The next year Frederick purchased an old paper mill in Ballston Spa, north of Albany, converting it to a chocolate factory, running both facilities simultaneously.

Frederick Bischoff died in 1942, and the Ballston Spa factory closed around 1945; the Sands Street Brooklyn facility was vacated in the early 1950s to make way for construction of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

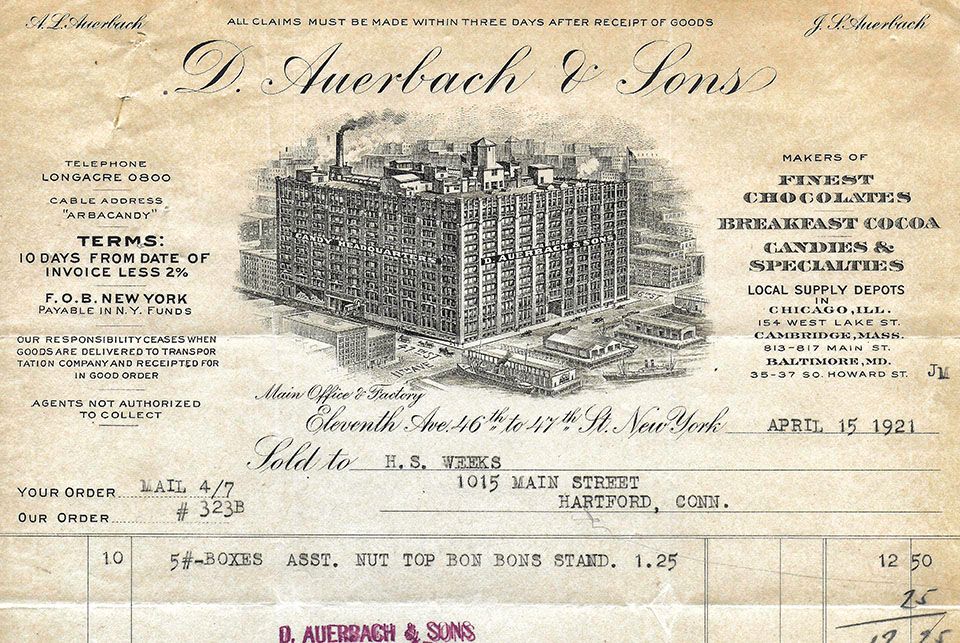

D. Auerbach and Sons

Not much is known about David Auerbach’s origin story, but it is assumed he and his family arrived in New York from Germany in the 1860s. We first take note of David and sons’ confectionery business in the 1890s at West 39th Street and 9th Avenue. David died in 1907, and in 1913 the Auerbach sons moved to an eleven-story factory at 636 11th Avenue at 46th Street. The firm’s specialty was its assortment of 5- and 10-cent candy bars filled with peanuts, almonds, marshmallow, maple-pecan, peppermint, coconut, pineapple, and raspberry.

Like other manufacturers, Auerbach offered delivery to service members via post exchanges and ship stores during World War I. Advertisements in the 1920s suggested, “for that in-between-meal hunger there’s nothing so good as an Auerbach Chocolate Sandwich – two dainty layers of smooth nutritious vanilla sweet chocolate.” Likely due to the onset of the Great Depression, the business dissolved in 1930. High-powered ad agency Ogilvy and Mather moved its headquarters to the old factory space in 2009.

Pirika Chocolate Company

The modest Pirika Chocolate Company launched with a $500 investment by John Randolph Stout in 1898, and steadily grew from its 1,000 square-foot space on Bergen Street, to a modern factory on Dean Street in 1903. By the mid-1910s, daily production reached four tons of chocolate and cocoa, and the factory employed three hundred workers. Records show that Pirika’s government contracts for 1918 alone amount to almost 140 tons of chocolate and candies. A story relayed by a Brooklyn newspaper in 1919 claims that an order for a ready-to-drink cocoa mix placed by the U.S. Army was so large, and required so short a turnaround, that Pirika, “subordinating self-interest to patriotism,” shared its formula with ten other manufacturers to satisfy the requested volume on time.

Riding the wave of a chocolate boom that began to crest in the early 1900s, Stout and his sons found great success as a relative newcomer to the industry. Perhaps betting big on continued growth at the outset of Prohibition, their post-war profits were immediately invested in constructing a new building in 1920. Located a few blocks from the 972 Dean Street factory, a February 1925 stock pitch claimed the newer space had a production capacity “in excess of fifteen tons of candy per day.” A month after that advertisement posted, Pirika declared bankruptcy, owing creditors a staggering $500,000 (over $7 million today). Evidence surfaced that showed the company was in bad financial shape at least six months prior to petitions being filed, and John Stout’s sons declared bankruptcy as individuals in April. A year-long investigation ensued to determine the cause of the company’s apparent sudden failure.

A note to any ambitious chocolate makers who wish to breathe life into the former Pirika factory, it appears to be for sale:

Hershey

We last saw Milton Hershey in New York City in the 1880s. After a two-year stint working at Huyler’s followed by a short-lived business venture, he moved back to Pennsylvania in 1886 to open what became the Lancaster Caramel Company. Inspired to make chocolate in the mid-1890s, Hershey produced cocoa and sweet dark chocolate before launching his milk chocolate bar around 1900. Following the sale of the caramel business, Hershey broke ground in Derry Township for a new factory, completed in 1903.

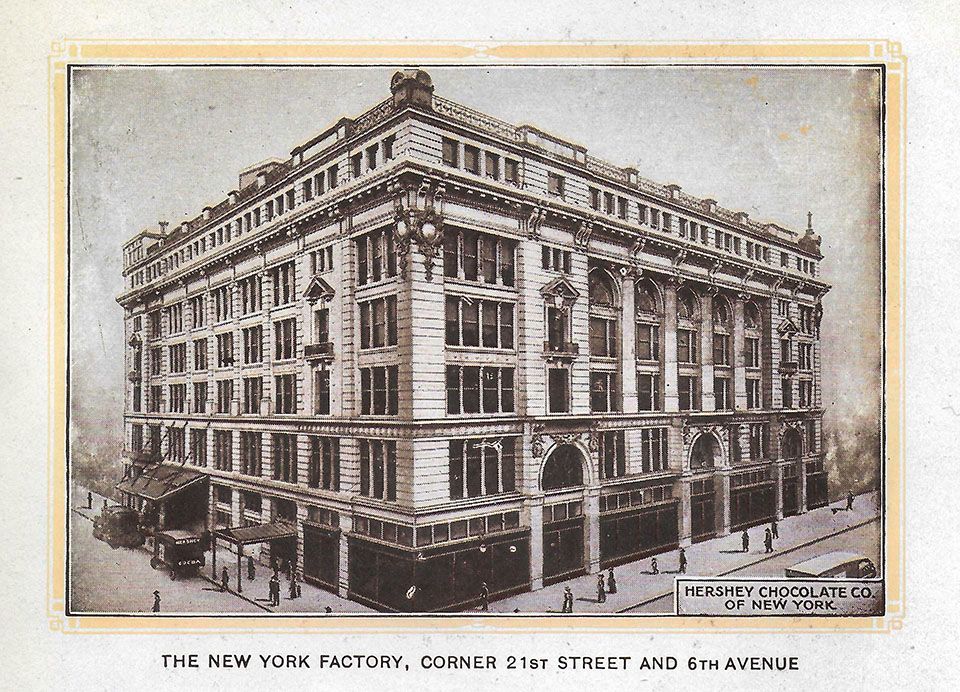

Hershey returned to New York by 1915, first with a retail store at 125 West 42nd Street between Bryant Park and Times Square (and just down the street from the shop he was forced to close thirty years prior). In 1918 the company signed a lease on the ornate Beaux-Arts building at 675 6th Avenue, between 21st and 22nd Streets – the former home of the Adams Dry Goods Store. As the story goes, the new factory was originally intended for the manufacture of chewing gum, a vanity project of sorts that Hershey developed a few years earlier. While gum production did carry on in fits and starts, the line ultimately failed, and manufacturing ceased by 1924.

At some point, a modest suite of chocolate machinery was installed; it’s unclear whether the layout served as a pilot plant for small scale research and development, or if any significant chocolate production took place there at all. The small factory must have been considered an asset of some importance, as it was included in promotional pamphlets published in the 1920s. A set of photographs taken in 1920 show several roasters and a winnower on the building’s sixth floor, a fifth-floor paper box factory, a trio of day-mixers on the fourth floor, and various ground floor packaging lines. Also used as a warehouse, Hershey renewed the lease into the 1930s. Today, the building is largely office space, the ground-floor retail storefronts occupied by a Trader Joe’s market and a Michael’s craft store.

Note: When 6th Avenue was extended southward to Canal Street in the mid-1920s, it forced the renumbering of existing addresses; prior to its current position at 675, the Hershey factory’s address was 339 6th Avenue.

The mid-20th century will see a geographical repositioning of chocolate manufacturing, increasingly concentrated in Pennsylvania and the Midwest. Big brands become bigger, jostling for ever greater market share. The New York makers that helped usher in the industrial age of 'big' chocolate would eventually be consumed by it. As the series continues, we'll follow the decline of the city's manufacturing, and a rebirth, of sorts, with the emergence of artisan craft chocolate in the early 2000s.

By now, we've explored nearly two hundred years of chocolate culture in New York city, each installment accompanied by follow-up discussions on Thursdays in the The Chocolate Life Room on Clubhouse.